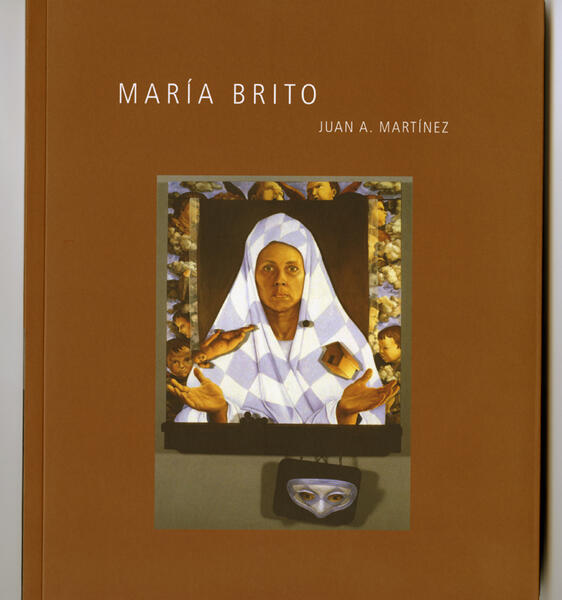

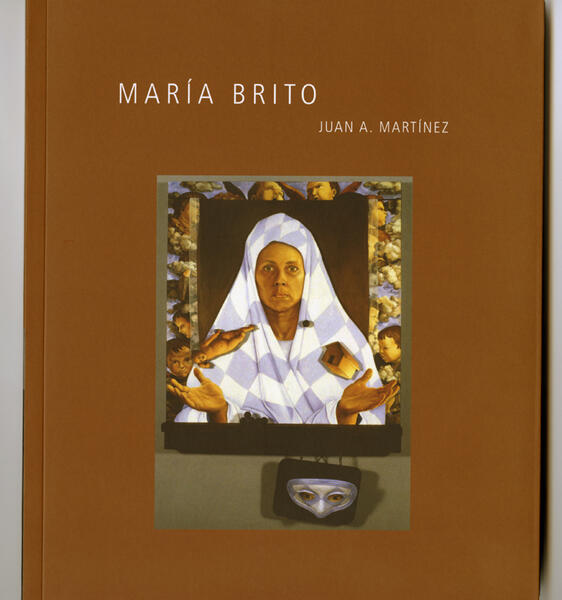

María Brito

and her anxious interiors

Reading Juan A. Martínez’s María Brito is equivalent to exploring an immense retrospective in which the chronological structure is crossed by multiple levels of meaning. The “curator” − the writer, in this case − has succeeded in documenting the paradoxes of the artist’s “autobiographic labyrinth” and her relationship with the historical social context in such a way that he conveys to the viewer a revealing vision of the dimension of her work, but also the conviction that no artist is an island.

María Brito, painter, sculptor, installation artist, arrived in the United States with the generation of the “Peter Pan” program, marked by the experience of an abrupt deracination, indissociable from the common experience shared by an epoch. Martínez has had the ability to recreate it simultaneously, situating it in the bi-cultural frame work of Cuban art and the art of the United States, but discovering in a parallel way Brito’s irreducible subjective baggage. He understands that while “issues such as dislocation, memory, loss, protest, liberation, were clearly based on her particular experience, they strove to attain a universal resonance.”

As Chon A. Noriega specifies in the preface, Martínez accurately characterizes the artist’s domestic installations under a title excerpted from an exhibition, Anxious Interiors, curated by Elaine K. Dines, in which Brito should have been included. His statement constitutes a sort of historical reparation. He comes to this conclusion after a survey that explains her initial relationship with pottery and later highlights the “seminal” character that, already in 1979, distinguished Underneath It All Where Everything is Ancient and Common to Every Individual (1979), the work that marks the moment when she understood “that her ideas were best expressed in mixed media, especially wood and found objects, and in a human scale facture.” The chapter devoted to the assemblages created between 1980 and 2000 and sub- divided into boxes, interiors and objects, reveals the strength with which Brito irrupts into the spectator’s space. Martínez manages to connect her early experience as a migrant in search of discarded objects that can be recovered with a “distant familiarity” with the Merz de Schwitters project. He also resumes Lynette Bosch’s analysis, which highlights in her assemblages the predominance of the object over the figure (which it replaces), and the way in which the use of juxta- positions suggests different levels of discourse rather than a linear narrative. The connection that becomes established between the emotional and symbolic content in her works and the Catholic iconography of her childhood, as well as the way in which she reconstructs the relationship between the portrait and the public domains is particularly interesting.

Martínez approaches the artist’s interiors on the basis of the structures of signification correlated to psychological notions such as the absence-presence duality, or of the function of the mirror as reflection-negation of reality, as well as of the way of assuming the female body as a space to contain not the masculine desire, but the construction of identity, memory and an inner world.

Likewise, he highlights the way in which, after producing the celebrated “anxious interiors” in the 1990s, as for example El patio de mi casa, or Whitewash, where she addressed the issue of the confinement of the statu quo, she began to give precedence to social issues. In works such as Trappings, the oppression of the religious dogma, forms of control, may be observed, while in an installation like Pero sin amor, she contextualizes the exodus of the Cuban “balseros”, without the character of signification ceasing to be elusive and open.

The chapter Apropiación y alegoría explains the emergence in her sculptures of three dimensional anthropo-zoomorphic figures that incarnate difficult times such as the Great Depression (Of Mice and Men), or that transform Goya’s Black Paintings into a series addressing social diseases and human ignorance.

The chapter Breaking Barriers analyzes the process of insertion of her work in North American art on the basis of an iconography which was hybrid in its origin and multiple in its scope: the Latino cultural heritage, the dialogue with artistic contemporaneity, and the meta-artistic reflection in which the conceptual is not alien to the exploration of the self.

The statement that closes the book, highlighting how María Brito has made social, gender and artistic forces of a diverging nature converge to render her art representative of American art” is, like the entire book, a contribution to the ongoing construction of a less hegemonic and more inclusive history of art.