A Matter of Archives

One of the most important events concerning Latin American art took place in Houston at the end of January, and it may have gone unnoticed to many people.

We are referring to a project backed by a budget of over 50 million dollars which has been generated by the International Center for the Arts of the Americas (ICAA) of the Museum of Fine Arts Houston. Its goal is to afford public access via the Internet to a digital archive which, by 2015, will include more than ten thousand facsimiles from primary sources on the history of 20th century Latin American art. What is meant by ‘primary sources’ are documents such as recordings, artists’ writings, correspondence and catalogue-like publications, magazines, etc., created or otherwise produced during the time under study. The website www.ICAADOCS.mfah.org already contains a little over 2,000 documents from Argentina, Mexico and the USA. According to the official press release, documents from Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Peru, Puerto Rico, Venezuela and the USA will be incorporated in the years to come.

In her inaugural lecture, Mari Carmen Ramírez, Wortham Curator of Latin American Art and Director of the International Center for the Arts of the Americas (ICAA), at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, explained that this project began in 2001 with a group of 35 experts who helped to forge the Center’s guidelines. Ramírez added: “The common concern of all those who attended the meetings, many of whom are here today, was the precariousness or the non-existence of an archival and publications infrastructure in Latin America and in the Latino communities in the USA. As a result of this situation, we feared that the intellectual production of the artists from those countries might be lost forever.” (Lecture, MFAH, January 19, 2012. The author’s translation).

Let us therefore see how this archive works. We rummaged through the virtual shelves of ICAADOCS.mfah.org. Our penchant for photography led us to look for something in that specific field. We chose randomly: Grete Stern, nothing, Graciela Iturbide, nothing. We tried “Tina Modotti” and found the facsimile document #776694 featuring a letter published in the bimonthly newspaper El Machete (Mexico F.D., January 19, 1929), Contra una canallesca mentira: Tina Modotti es una luchadora (Rebuking a despicable lie: Tina Modotti is a fighter), signed by Enea Sormenti, alias Vittorio Vidali. The provenance of the document is the CURARE, space for art criticism in Mexico City managed by the researcher Adela Cedillo. We assume that the summary of the document is Cedillo’s: “The League for Support of Persecuted Fighters forwarded a letter to the editors of El Machete written by Enea Sormenti, secretary of the Mexican Anti-Fascist League. The purpose of the note was to defend the reputation of Tina Modotti, whom José Magriñá had accused of being a fascist spy. Sormenti maintained that Modotti’s family was well known in the anti-fascist milieus, listed the position that Modotti occupied in organizations linked to the Committee for the Defense of Victims of Fascism and the International Red Aid, thus reiterating the solidarity of anti-fascists vis-à-vis the slandered Italian activist.”

The underlying implications in this document are explained by the critical commentaries that follow, which we suppose may also be attributed to Cedillo: “In the context of the murder of the communist Julio Antonio Mella in Mexico City on January 10, 1929, the press unleashed an insidious harassment campaign against Tina Modotti (1896-1942), a photographer and the sentimental partner of the Cuban activist, who was the co-founder of the PCC (Cuban Communist Party) together with Carlos Baliño. The homicide provoked an avalanche of exorbitant speculations, including some that regarded Tina as the author or the originator of a crime of passion. It is striking that, of all the rumors disseminated in those days, Vittorio Vidali, alias “Enea Sormenti” (1900-83), should have chosen Magriñá’s statements to embark on a defense of Modotti, since the Italian hired assassin was precisely the person marked by the Mexican Communist Party as one of the actual perpetrators of the murder. Two aspects stand out in Vidali’s letter: on the one hand, his efforts to clarify to the Mexican communists something that none of them had even suggested (that is, Modotti’s secret fascist affiliation); on the other hand, the absolute omission of any reference to the Mella case. Although his activities in our country (Mexico) have been little studied, Vidali’s arrival in Mexico in 1927 responded, among other factors, to the coordination of the regional activities of the International Red Aid (an organization that masked secret operations of The Third, Communist International). The dark aspects of this figure have led some researchers to envisage him as Mella’s possible murderer, although the most generally admitted hypothesis indicates that the Cuban dictator (1925-33), Gerardo Machado (1871-1939), ordered his elimination. In any case, the event allowed Vidali to bring Tina under his influence, an influence from which the photographer would not escape until her own death.”

Cedillo’s critical comments make no mention of the violent conflicts between Stalinist and Trotskyist supporters at that time, nor of Mella’s sympathy for Trotsky. Those omissions give grounds for the hypothesis of the Stalinist Vidali’s participation in Mella’s homicide. After Mella’s demise, Modotti was Vidali’s sentimental partner for many years. According to the Wikipedia, the romantic triangle Mella, Vidali y Modotti had already been disclosed in Diego Rivera’s mural painting, En el Arsenal (1928) − a year before the murder. The right end of the mural shows Modotti holding an ammunition belt. In the background, the partially hidden face of Vittorio Vidali suspiciously observes Modotti gazing lovingly at Mella. .

A version of the act of bloodshed appears in Elena Poniatowska’s novel, Tinísima. But that narrative seems to exonerate not only Modotti but also Vidali. However, in the Wikipedia we find the following information: “In 1941, a few months before her death, Tina Modotti expressed to Jesús Hernández, a former minister during the Republican government, the following about Vittorio Vidali: “…He is nothing more than a murderer, and he dragged me to commit a monstrous crime. I hate him with all my soul. But I am obliged to follow him until the end. Until death…”

We have witnessed how this little document included in the ICAADOCS leads us to a mural painting by Diego Rivera, a novel by Elena Poniatowska, a series of photographs by Weston, another series by Modotti, several films by and about Modotti, and a poem by Neruda. It also leads us to wonder: How did Modotti end up as the sentimental partner of Vidali, Mella’s alleged murderer? Was Modotti implicated in the Cuban’s assassination?

Since the Museum of Fine Arts Houston created the Latin American Art Department in 2001, it has implemented an admirable campaign of modern and contemporary Latin American art exhibitions and acquisitions. The ICAADOCS Project is a part of that campaign. The end result of the project will be visible when it has fulfilled its goals, but in the meantime, it can provide us access to more documents than we could have found in the majority of the already existing archives. Furthermore, its clever utilization may lead users to suggest to ICAADOCS other sources to be incorporated and other important fields that must be encompassed within its scope.

-

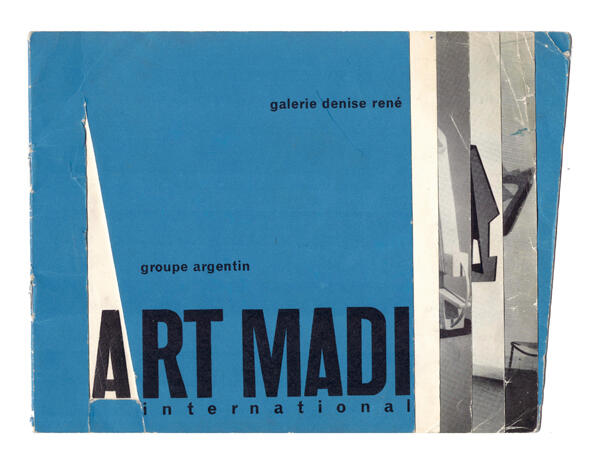

Cover for Groupe argentin Art Madi International [Argentinean Group Art Madí International], exh. cat. (Paris: Galerie Denise René), 1958. Collection of Gyula Kosice, Buenos Aires. ©

Cover for Groupe argentin Art Madi International [Argentinean Group Art Madí International], exh. cat. (Paris: Galerie Denise René), 1958. Collection of Gyula Kosice, Buenos Aires. © -

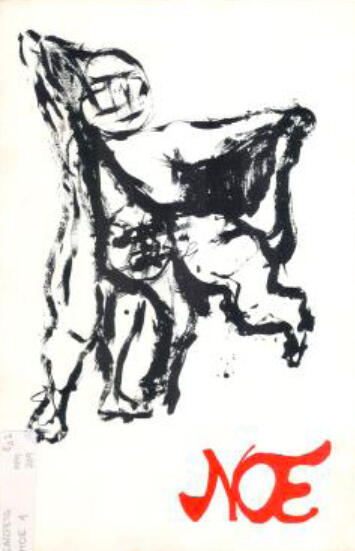

“Presentación de mi obra a un amigo” *Introduction of my work to a friend], in Noé, exh. cat. (Buenos Aires: Galería Van Riel), 1960. © Data: PERMISSION GRANTED

“Presentación de mi obra a un amigo” *Introduction of my work to a friend], in Noé, exh. cat. (Buenos Aires: Galería Van Riel), 1960. © Data: PERMISSION GRANTED