Camnitzer:

The Parable of Conceptual Suspiciousness

In Luis Camnitzer’s view, suspiciousness – that way of suspecting or mistrusting − configures a method of creation that takes the tools of conceptual art to a borderline, where it inquires into the contemporary art system as a whole and into its methods to project itself in relation to the economic and institutional structures that control it.

In this sense, it generates a sophisticated series of alarm devices that function in the first place in a mirror-like way, confronting the artist with the intentions and resources of his/her own creative process and with the paradox of critical works which, however, aspire to insert themselves within recognition spaces and which, on the other hand, displace the notion of Brecht’s ‘breaking the fourth wall’ to an alert relationship between the spectator and the spectacle of the artwork. The result is that the former, far from allowing him/herself to be easily seduced by the mechanisms that legitimize − and render inactive − the initial critical power of the works, remains on his/her guard, aware of the fact that economic voracity may tame even the most iconoclastic art.

Suspiciousness –exercised in a scathing way − is the sign that marks a body of work that extends Joseph Kosuth’s contributions and the structuralist reflection that linked reception theory and language to the art market system itself and to institutional criticism. But above all, the artist intercepts himself by abiding by an endless questioning of the intentions behind his own work. This does not mean that, even being someone who is better known for his work as a critic and a teacher than for his efforts to become part of the art system − someone who has not, therefore, made a living from selling his works − the artist should have “cut himself off” to the point of working in the shadows, or without aspiring to earning recognition. Instead of unfinished works, he has maintained, with remarkable constancy, continuity in the development of series that resort to the same question that interrogates its validity to reaffirm the presence of the author, his signature.

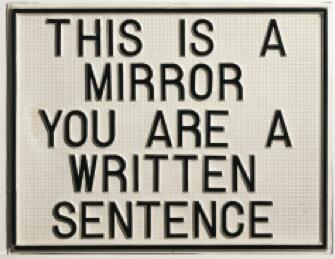

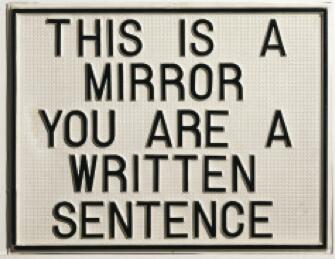

If his first conceptual work, titled and formed by the phrase Esto es un espejo. Usted es una frase escrita/This is s mirror. You are a written phrase (1966-1973), may be associated to Monsieur Teste’s earlier expression, “the Universe exists only on paper,” it is undoubtedly a pioneering work, parallel to the explorations of the use of typographic elements by Lawrence Wiener, who resolved the making of the work through a statement in which he concluded that the piece need not be built, which however constituted, per se, the facture of the work. That same textual process of negation, which ironically constructs its own alternate affirmation, is imbued in Camnitzer’s work with a particular sarcasm that perhaps has a stronger presence in Latin America than in other parts of the world due to the fact that the strategies of concealment and reappearance date back to the cultural practices of mischievous −ingenious − survival of the indigenous covered by other cultural wrappings. The exhibition Luis Camnitzer at El Museo del Barrio, New York, allows the viewer to become immersed in the distrustful rules of his conceptual game.

As part of an exercise he would later develop in the New York Graphic Workshop together with Liliana Porter and Guillermo Castillo, whose experimentations incorporated the conceptual in graphic art, in 1967 Camnitzer created Rubber Stamps to print phrases-images such as A perfectly circular horizon, or simply his own signature, which plays with unlimited reproduction and the relationship between a copy and the original. The exhibition groups together different works whose matrix is the self-reference to the artist’s signature. In 1968, 1970, and 1972, he produced three self-portraits: plain etchings, basically identical. − with just his name in capital letters in the centre − in which only the date changes. In 1972 he created Fragments of a Signature to be sold by centimeters, deconstructing the commercial relation through the author’s signature. The idea extended to other mediums and materials, in such a way that the signature is sold by weight, by slices or by inches, or, as is the case in Plusvalía (Capital Gain), the value of the work shifts to a glove that is worn by different artists and its prize multiplies with each new contact. The meta-artistic does not question the creative process, but rather that of the parallel system that commercializes the transformation of artworks into fetishes. The work is a witticism that tends to expose this system, and in this sense it is apparently a threat to commodification, yet −obviously − it increments its own prize through the mirror-like play that reveals the speculation processes.

In Selbstbedienung (Self-service) 1996-2010, a work titled in German (the language spoken in his birthplace), the viewer stamps Camnitzer’s signature on photocopies of the artist’s statements, such as “The soul of art lives in the signature”, or “Onesignatureisaction;twosignaturesaretransaction”.Each sheet of paper can be freely removed, and each person decides if the aura of the signature is enhanced or reduced by the possibility to reproduce it and by each person’s free choice as to where to stamp the signature on the page. The artist’s portrait casually rendered by a pencil tied to a string moved by an electric fan implies a reference to the Duchampian tendency to demystify. But consumption is always deceitful, and Camnitzer, as is well known, plays suspiciously with the ambiguous.

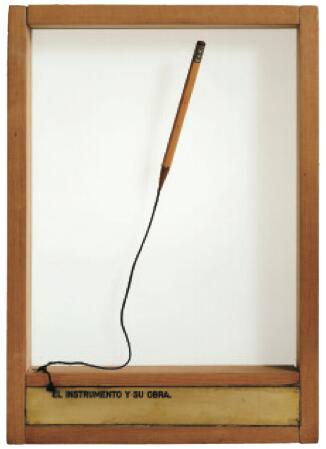

Another exhibition space showcases the Boxes that Camnitzer made in the 1970s using wooden frames and glass. The inscriptions in the boxes were prior to the works, yet as is the case in Etching by Picasso, “surrealist model and sculpture [...] transformed into a single line, into a piece of thread, into a spiralinitspreciselongitude”,theviewercorrelatesthecoiled black thread with the sarcastic deconstruction of the piece. It is hard to stop smiling when faced with the horizontal wire that divides in two the wooden frame in the work titled Real Edge of the Line That Divides Reality From Fiction, or when noticing, when one views The instrument and its tool, the shrewdness with which the artist disrupts the expectations associated to the material produced by a pencil when he replaces the line with a filament of a rope. This procedure reflects forms of humor that partake of the cognitive function of self-referential art. In The perception of one self, in what appears to be an empty frame the viewer may discern the holes that perhaps were part of the support for an image. In any case, the exhibition Luis Camnitzer incarnates the artist’s conviction regarding the close association between art and pedagogy: a tour of this exhibit is the equivalent of an inaugural lesson on Conceptual Art delivered by an artist with sufficient suspiciousness to turn his thought matrix into an inexhaustible method of creation and reproduction.

-

This is a mirror. You are a written sentence, 1966-1968. Vacuum formed polystyrene mounted on synthetic board, 19 x 24.6 x 0.59 in. Daros Latinamerica Collection, Zürich. Photo: Peter Schälchli, Zürich. Esto es un espejo. Usted es una frase escrita, 1966-1968. Poliestireno formado al vacío, montado sobre panel sintético, 48 x 62,5 x 1,5 cm. Colección Daros Latinamerica, Zürich. Fotografía Peter Schälchli, Zürich.

This is a mirror. You are a written sentence, 1966-1968. Vacuum formed polystyrene mounted on synthetic board, 19 x 24.6 x 0.59 in. Daros Latinamerica Collection, Zürich. Photo: Peter Schälchli, Zürich. Esto es un espejo. Usted es una frase escrita, 1966-1968. Poliestireno formado al vacío, montado sobre panel sintético, 48 x 62,5 x 1,5 cm. Colección Daros Latinamerica, Zürich. Fotografía Peter Schälchli, Zürich. -

The instrument and its tool, 1976. Pencil, rope, engraved brass plaque, glass and wood, 13.8 x 9.8 x 2 in. Daros Latinamerica Collection, Zürich. Photo: Peter Schälchli, Zürich. El instrumento y su obra, 1976. Lápiz, soga, placa de bronce grabada, vidrio y madera, 35 x 25 x 5 cm. Colección Daros Latinamerica, Zürich. Fotografía Peter Schälchli, Zürich.

The instrument and its tool, 1976. Pencil, rope, engraved brass plaque, glass and wood, 13.8 x 9.8 x 2 in. Daros Latinamerica Collection, Zürich. Photo: Peter Schälchli, Zürich. El instrumento y su obra, 1976. Lápiz, soga, placa de bronce grabada, vidrio y madera, 35 x 25 x 5 cm. Colección Daros Latinamerica, Zürich. Fotografía Peter Schälchli, Zürich. -

Living Room (detail), 1969/2010. Photocopy on adhesive vinyl on wall and floor. Overall dimensions variable. Photo: Dominique Uldry, Bern. Living Room (detalle), 1969/2010. Fotocopia sobre adhesivo vinílico sobre pared y piso. Dimensiones generales variables. Fotografía: Dominique Uldry, Berna.

Living Room (detail), 1969/2010. Photocopy on adhesive vinyl on wall and floor. Overall dimensions variable. Photo: Dominique Uldry, Bern. Living Room (detalle), 1969/2010. Fotocopia sobre adhesivo vinílico sobre pared y piso. Dimensiones generales variables. Fotografía: Dominique Uldry, Berna. -

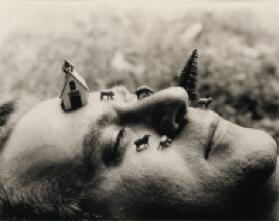

Landscape as an attitude, 1979. Laminated b/w photograph, 11 x 14 in. Daros Latinamerica Collection, Zürich. Photo: Peter Schälchli, Zürich. El paisaje como actitud, 1979. Fotografía b/n baritada, 28 x 35.5 cm. Colección Daros Latinamerica, Zürich. Fotografía Peter Schälchli, Zürich.

Landscape as an attitude, 1979. Laminated b/w photograph, 11 x 14 in. Daros Latinamerica Collection, Zürich. Photo: Peter Schälchli, Zürich. El paisaje como actitud, 1979. Fotografía b/n baritada, 28 x 35.5 cm. Colección Daros Latinamerica, Zürich. Fotografía Peter Schälchli, Zürich.