Crisisss. Art and Confrontation in Latin America

Palacio de Bellas Artes - Ex Teresa Arte Actual, Mexico City

I still do not know of a postmodern poverty. Independently of globalization and decentralization, poverty continues to be the same thing, Gerardo Mosquera remarks at the end of his introduction for the book Beyond the Fantastic. Contemporary Art Criticism from Latin America. Viewing the exhibition Crisisss. América Latina. Arte y confrontación. 1910-2010 (Crisisss. Latin America. Art and Confrontation. 1910-2010), it occurred to me that an imaginary conciliation between postmodernism and poverty might be found in the concept of “post-misery”,which a well-informed Brazilian drug trafficker cited some time ago in an interview published by O Globo. Post-misery (“shit with chips”, Marcos Camacho Marcola says in that interview), expresses that unbalanced combination between the liberal, technocratic and post-media dynamics of contemporary capitalism and the realities of poverty, marginality and violence that the official texts try to evade continually by means of self-affirmative constructions.

One of the exhibition’s keys might be that it shows the strength of an art which restores visibility to post-misery in a new semantic and epistemological level. Mugre (Filth), a series of performances that Rosenberg Sandoval carried out between 1999 and 2004, in which he carried destitute people inside the art gallery on his shoulders, is one of the works featured at the exhibition that best illustrates that strategy of re-visualization and re-semanticization of areas of reality which are generally obliterated in totalizing discourses. Teresa Margolles’s Ajuste de cuentas (2007) constitutes an operation of recycling and infiltration of the waste material of post- misery, which then becomes the raw material for luxurious fetishes (jewels reconstructed with elements found in the crime scenes associated to drug trafficking).

Featured in the Palace of Fine Arts and Ex Teresa Arte Actual, in Mexico City, the exhibition Crisisss. Latin America. Art and Confrontation. 1910-2010, stages through the display of over 200 works by around a hundred artists, a reading of Latin American art in its confrontational relationship with power, in the context of the hundred years that followed the Mexican Revolution. It also proposes a decoding of social tensions in the context of the modern and post-modern history of Latin American political art, and a non-conformist reading of nationalism − the latter summarized in an extremely accurate way by Santiago Sierra’s sound installation, in which the national anthems of several countries can be heard simultaneously (Himnos nacionales, 2007), or in Wilfredo Prieto’s forceful installation, displaying the flags of different countries, in which the colors have been eliminated (Apolítico, 2001).

There are works in which confrontation rather seems to be oriented against the viewer through a double effect of seduction and strangeness, as is the case in Mona Hatoum’s installation, Impenetrable. Although it might be considered that the work of this artist has little to do with Latin American art, what is interesting about this piece in the context of Crisisss is that it becomes a reference to Jesús Soto’s Penetrables, while at the same time it inverts all its senses, for instead of the chromatic, kinetic and ludic structure in Soto’s work, what we see is s somber, tense and aggressive structure, built with barbed wire. In any case, the gesture of the curator is not without a touch of irony similar to the one that could be perceived when he included artists who were not Brazilian in the exhibition 20 Desarreglos, which became, in Mosquera’s own words, an “anti-panorama” of Brazilian art. Crisisss also has something of an anti-panorama or of a “disorganized” panorama of Latin American art in which Rivera, Orozco and Siqueiros share the space with Gómez- Peña, ASCO and Las Yeguas del Apocalipsis (The mares of the Apocalypse). After all, this is not a historicist exhibit (it is not even organized in a chronological order), nor does it adjust to the turn-of-the-century texts which have tried to define, or at least to illustrate, on the basis of artistic practices, the ungraspable Latin American identity. In any case, what the show suggests is that the context in which this identity is enunciated and represented is the crisis context.

According to this reading, Latin American art should be regarded as a critical art, and it is not inappropriate also to consider it an art that is self-critical. Crisisss is an exhibition of nonconformist art, which may lead to the assumption that nonconformism constitutes the raison d’être of art in a crisis context. It also leads to the assumption that the first objective

that nonconformist art aims to combat is discourse, more specifically, the discourse through which the exercise of political power is justified and staged. Hence the translinguistic effectiveness of works such as José Angel Toirac’s video Opus (2005), in which Fidel Castro’s voice obsessively and meticulously repeats figures while the screen remains black, and only the sequence of numbers is visible, like a technological abstraction that dematerializes the figure of the leader, ironically recharging the dimension of his aura.

Although it has seemed inevitable for part of the local public to interpret this exhibit as a critical rereading of the Centennial of the Mexican Revolution, the truth is that the logic behind it is more complex. In fact, the weight of the exhibition rests upon the art of the second half of the 20th century, and this is not necessarily a question of quantity. It may be suspected that if nonconformist artistic practices gained greater strength as of the 1960s, it is also because that period marked the heyday of the dictatorships in Latin America and, consequently, the boom of resistance movements. During that period, also marked by the paradigm of the Cuban Revolution (which, oddly enough, generated one of the most peculiar and long-lived dictatorships in the American continent) the discursive density of Latin American art was reformulated and its capacity to recycle, oppose, and also parody the discourses of power.

Part of the consistency of this exhibition is derived from the fact that it allows the viewer to recognize many of the issues addressed by art criticism and art history in Latin America: the interaction between popular and mass culture, the appropriations, the recycling and the parodies or the symbolic rearrangement of the notions of center and periphery, or of power, subordination, and resistance. This show does not only make reference to the history of Latin America in the past hundred years, but also to the logic that characterizes the evolution of art as a language, at least in what respects its enunciation capacity and its confrontation with the authorities.

-

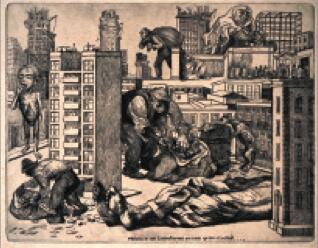

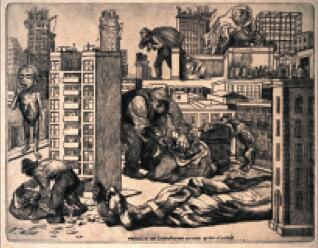

Alfredo Zalce. México is becoming a large city..., 1947. Burin engraving on paper, 16.6 x 21.3 in. Instituto National Institute of Fine Arts, National Museum of Engraving, Mexico. México se transforma en una gran ciudad..., 1947. Grabado a buril sobre papel. 42,1 cm x 54,2 cm. Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes, Museo Nacional de la Estampa, México.

Alfredo Zalce. México is becoming a large city..., 1947. Burin engraving on paper, 16.6 x 21.3 in. Instituto National Institute of Fine Arts, National Museum of Engraving, Mexico. México se transforma en una gran ciudad..., 1947. Grabado a buril sobre papel. 42,1 cm x 54,2 cm. Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes, Museo Nacional de la Estampa, México. -

Juan Downey. Yanomami, 1976. Contemporary print, 177 x 259.8 in. Marilys B. Downey Collection. Y anomami, 1976. Impresión contemporánea, 450 x 660 cm. Colección Marilys B. Downey.

Juan Downey. Yanomami, 1976. Contemporary print, 177 x 259.8 in. Marilys B. Downey Collection. Y anomami, 1976. Impresión contemporánea, 450 x 660 cm. Colección Marilys B. Downey. -

Jimmie Durham. Thinking of you, 2008. Painted steel and aluminum, 196.8 x 39.4 x 39.4 in. Courtesy of the artist and Michel Rein Gallery, Paris.

Jimmie Durham. Thinking of you, 2008. Painted steel and aluminum, 196.8 x 39.4 x 39.4 in. Courtesy of the artist and Michel Rein Gallery, Paris.

Pensando en ti, 2008. Acero y aluminio pintados, 500 x 100 x 100 cm. Cortesía del artista y Galería Michel Rein, París. -

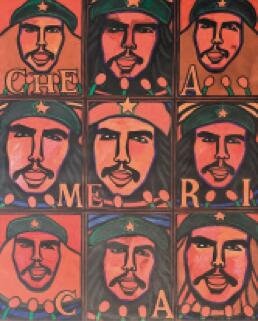

Raúl Martínez. Fénix, 1968. Oil on canvas, 78.7 x 70 in. National Museum of Fine Arts, Havana. Fénix, 1968. Óleo sobre tela, 200 x 170 cm. Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, La Habana

Raúl Martínez. Fénix, 1968. Oil on canvas, 78.7 x 70 in. National Museum of Fine Arts, Havana. Fénix, 1968. Óleo sobre tela, 200 x 170 cm. Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, La Habana -

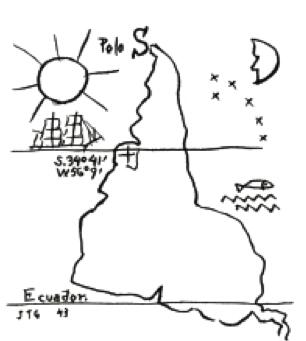

Joaquín Torres García. Inverted America, 1943. Ink on paper, 8.7 x 6.3 in. Joaquín Torres García Foundation, Montevideo. América invertida, 1943. Tinta sobre papel. 22 cm x 16 cm. Fundación Joaquín Torres García, Montevideo.

Joaquín Torres García. Inverted America, 1943. Ink on paper, 8.7 x 6.3 in. Joaquín Torres García Foundation, Montevideo. América invertida, 1943. Tinta sobre papel. 22 cm x 16 cm. Fundación Joaquín Torres García, Montevideo.