José Gurvich. The Pulse of a Restless Will to Change.

“In order to find life, I had to plunge into a free space, with only one hope: that at its bottom I might find my own voice”. José Gurvich

Born in Lithuania into a Jewish family, José Gurvich (1927-1974) arrived in Montevideo together with his parents and his sister at the age of four, escaping from the social and economic crisis that devastated Eastern Europe at that time, but also seeking freedom from the religious persecution that began to be felt in the early stages of World War II. Having settled in a working-class neighborhood in Montevideo, Gurvich showed an early inclination towards drawing, and as an adolescent, he alternated work in a raincoat factory with painting lessons from José Cúneo. Studying violin in 1943 he met Horacio Torres, who pleaded with his father, Joaquín Torres García, so that he would accept Gurvich as a student at the mythical “Taller del Sur” (Studio of the South). To his surprise, in November of 1944, his work was included in the exhibition Pintura moderna del Uruguay (Modern Painting of Uruguay), held at Comte Gallery in Buenos Aires, this being the first time that his work was shown outside of Montevideo.(1)

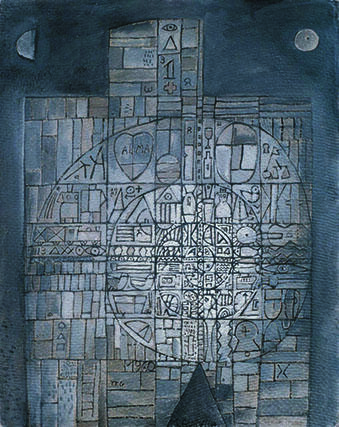

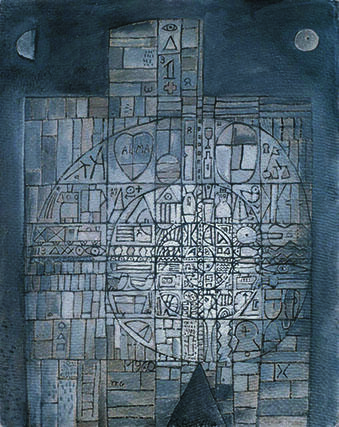

These shifts along the artist’s path ̶ together with the transformations and changes in his work ̶ are precisely the topics that Cristina Rossi highlighted in the exhibition titled José Gurvich. Cruzando fronteras (José Gurvich. Crossing Borders), which she curated, and which was held at the Museum of Modern Art in Buenos Aires (MAMBA) between August and October of the current year. Instead of resorting to the format of the classical retrospective, Rossi focused on the ability shown by Gurvich along his trajectory to move about freely, both in geographic and aesthetic terms. With a curatorial script based on four sections, the exhibition allowed the viewer to confirm the way in which Gurvich took his first steps following the precepts of Torres García, later to introduce gradual changes and modifications corresponding to the search for a voice of his own. Thus, starting from a series of small-format drawings and paintings on paper executed between 1947 and 1948 ̶ which zealously respect the postulates of Constructive Universalism: golden section, search for unity, placement of symbols within a grid ̶ the exhibition sheds light on a group of works on wood that Gurvich produced in Buenos Aires in 1960, when he visited the city in the company of his newlywed wife ̶ and that feature a singular assimilation of the constructive synthesis.

Choosing a palette that was not restricted to earth tones but that embraced chromatic contrasts, Gurvich would gradually reveal, as of the 1960s, a line of work that denoted his preference for a use of symbols of a personal ̶ and to a certain extent, even an autobiographic ̶ nature. Particularly significant in this respect are Pablo Thiago Rocca’s words when he states that “the process through which Torres’s pupils assimilated their mentor’s teachings and reached a personal path within the TTG acquires a great complexity insofar as the relationships within the group motivated their aesthetic influences, their intercrossing. There is a dynamics of psychological affinities and of teachers’ leaderships, and there is a natural decantation of that which has been learned, where each individual’s life experience plays an important role.” (2)

Thus, as of his marriage to Julia Helena Añorga, his works began to be populated by couples that referred to Torres García’s concept of the Universal Man, the one meant to recover cosmic harmony and dominate the base instincts of individual man. Towards 1964, after a journey through Europe, Gurvich settled with his wife and son in the Ramot Menashé kibbutz, in Northern Israel, where besides working as a shepherd, he made ceramic pieces and painted a large mural for the community dining-room. In fact, Gurvich taught ceramic techniques at the Torres García Studio before its closure in 1962, and his strong penchant for working in this medium was crystallized in the extraordinary ceramic sculptures he produced in New York during the last years of his life. The practice of an art which might articulate the creation of pieces linked to the fine arts as well as to crafts ̶ ceramics, painting, furniture, drawing ̶ was a commitment that Gurvich undertook during his formative stage under Torres García and that he did not abandon even when he reached his maximum potential of personal experimentation.

The beginning of the decade of the 1970s found Gurvich arriving with his family in New York, the city that would be his final resting place. According to Edward Sullivan,” For José Gurvich New York functioned as a laboratory to reconfigure his older techniques and subjects and investigate new possibilities”.(3)

The last section of the exhibition included works which made it possible to appreciate the strong impact that the pulsating and energetic rhythm of this city had on his poetics. The sketches in ink and watercolor on paper that Gurvich produced, inspired by his promenades in the city, illustrate his immediate impressions in response to the vitality and the dynamism of this new environment. Also, Sullivan points out that it is interesting to note the way in which “the New York notebooks” were presented as a tribute ̶ perhaps an involuntary one ̶ to similar works produced by Torres García in the same city between 1920 and 1922. But undoubtedly, the most experimental works that Gurvich produced in New York are those in which he shows an interest in transcending the borders between painting, sculpture and object, as is the case of Assemblage, the Collage in Orange Tones, and Triptych, both works dated 1972.

This exhibition, which gathered together approximately 90 works and was organized in collaboration with the Montevideo-based Gurvich Foundation, was complemented during the first few days following its inauguration by a colloquium coordinated by Rossi in which different aspects of the artist’s work were discussed, and which included the participation of Garbriel Peluffo Linari, Pablo Thiago Rocca, Edward Sullivan and the exhibition curator; the latter three authored the essays that comprised the book-catalogue that accompanied and documented the exhibit.

José Gurvich. Crossing Borders was undoubtedly an exhibition structured on the basis of a rigorous academic research, but which succeeded, nonetheless, in displaying lesser-known facets of the Uruguayan artist in an accessible tone that made it possible for the public to enjoy the event.

[1] The prompt admission of Gurvich by master painter Torres García and his inclusión in an exhibition that featured several already established Uruguayan painters such as Carlos Sáez, Pedro Figari, Rafael Barradas and the artist’s first painting teacher, José Cúneo, among others, is worth highlighting.

2 Pablo Thiago Rocca, “Notes for an iconography of the worker-artist” in José Gurvich. Crossing Borders, Buenos Aires, Museum of Modern Art-Buenos Aires, 2013, p. 118.

3 Edward J. Sullivan, “Gurvich in New York. A conflictive relationship” in José Gurvich. Crossing Borders. Op. Cit. p. 167.

(1) The prompt admission of Gurvich by master painter Torres García and his inclusión in an exhibition that featured several already established Uruguayan painters such as Carlos Sáez, Pedro Figari, Rafael Barradas and the artist’s first painting teacher, José Cúneo, among others, is worth highlighting.

(2) Pablo Thiago Rocca, “Notes for an iconography of the worker-artist” in José Gurvich. Crossing Borders, Buenos Aires, Museum of Modern Art-Buenos Aires, 2013, p. 118.

(3) Edward J. Sullivan, “Gurvich in New York. A conflictive relationship” in José Gurvich. Crossing Borders. Op. Cit. p. 167.