The Silence of the Voice

Exhumation, Memory, and Fragment

Gervasio Sánchez’s (Córdoba, 1959) exhibition, Desaparecidos, curated by Sandra Balsells and based on an original project by Rafael Doctor Roncero, has been simultaneously hosted by the CCCB (Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona), la Casa Encendida, Madrid., and the MUSAC (Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Castilla y León). The show has become, due to the imposed circumstances it depicts, a social event with ample cultural resonances and extremely clear implications − always devastating − for the dramaturgy on which the dominant discourses and the dictatorial verticalisms of modern terrorism are structured.

It is true that this is the first time that the work (or let us refer to it as the graphic document, for the moment) of a photojournalist is shown in three of the most important venues within the institutional circuits of contemporary art in Spain, which implies a large-scale operation and an inconceivable, titanic effort on the part of all its agents and coordinators. It is also true that the show constitutes a categorical document or restitution statement in the face of the exultating apathy of man (of the cultural being) whose animal humanity has been transcended, and it therefore implies an exercise of honesty and justice, of dignity and decorum. An exercise that may only be interpreted in artistic, journalistic, or literary terms − this borderline reductionism makes no difference − insofar as it is always, and above all, a demonstrable political exercise, the adoption of a stance.

However, I believe that independently of the aforementioned, this exhibition has a great virtue, that of becoming the testimony of an epoch, of a moment in culture in which generalized violence appears to be the symbol of the present time and in which violence itself puts to the test the very rhetorical and ideological mechanisms that promote it and deny it.

Gervasio Sánchez proclaims three great warnings in his exposition proposal. In the first place, he highlights the dangers and the consequences of amnesia for the culture system when the former is used as a palliative or prophylactic measure to counteract the unquestionable eloquence of truth. In the second place, it shows that there are no “collateral damages” but only “entirely real damages”, poignant, hurtful, devastating for the dignity and the integrity of the being (both in its human and its cultural dimension) which undergo the maneuvers of the inevitable politicians, many of them aimed at deterrence or concealement, and terribly scandalous. In the third place, it reaffirms the fact that in the present, history and culture, both being fictionalized writings, cannot hesitate, they cannot afford the idle pursuit or the hierarchization of the past in accordance with a selective principle, given that it is memory, and only memory (in its less rigorous totality) that makes it possible to provide an order and consistency to the text of the future.

Not under any circumstances can torture and its consequences in terms of the individual’s psychology and the landscapes left in its victims’ bodies be compared to the cruelty of forced disappearance as the recurring instant of a terrorist action that denies, destroys, forgets, and buries. The tortured person has −after all− a possibility of resurrection when freed from his/her tormentors, a possibility to become free from pain; instead, the “disappeared” lives in the silence of the voice; he/she wanders in the ins and outs of the void, in the threshhold of nothingness, in the greatest and most frightening deafness of a latent absence which does not even allow for the outlining of a silhouette.

To torture is to damage, to ill-treat, to humiliate; to torture is to re-write the person’s body and dignity in other dimensions that will certainly never be able to leave behind the traces of the pain that has been experienced. But, far from this, to make someone disappear is to suppress; it is to resort to the pretext that oblivion marks the beginning and the end of life, to encourage escape, to blurr the traces, to disdain and mock life itself. Making people disappear presupposes the implementation of a sophisticated game (sordid and sarcastic) of alienation. Torture and disappearance open up a very wide repertory of violent mechanisms that will be present, with extreme radicality, in cultural and political discourses of any type.

Therefore, it is a question of demanding very different abstractions and very different thought maps that may guarantee an honorable position when faced with these issues. Would it not be wise to inquire into the opposite process, in which the pertinence and honesty of the discourse do not negotiate the legitimization of the process at the expense of its social responsibility? That is to say: to observe the mechanisms that shift and emerge when the gaze of the artist, who looks at the ‘other’ or not only at the ‘other’, or not exclusively at the ‘other’, manages to revert the dominance/subalternity paradigm. Must the ‘other’ always be satisfied with the gaze that is cast upon him? Or isn’t he himself capable, through the intense exploration of his cultural endeavors and ambitions, of reformuilating that gaze and making an impression on the one that looks and observes from the outside? Confronted with so many dilemmas that are, in turn, so vital, Gervasio permits himself to answer and at the same time to doubt by virtue of the moderation which must necessarily be the epistemologic method and standard in any outward focused work, in any work focusing on the cultural pain of the ‘others’. Few photographers in Spain (I abide by the facts) have managed to grasp with such degree of intensity and essentiality the feeling of pain of the whole human family spread throughout very different contexts, very distant from one another, but sharing the same overwhelming experience: loss, grief, the picture of absence. In a terrain that is as dangerous as it is prone to exoticist seduction, Gervasio Sánchez has been capable of creating through the photographic image, the cosmos-logo that diagnoses the most intricate mechanisms of grief resulting from forced, imposed disappearance. These snapshots become kinds of tattoos in the written body of memory that aches and cries. “Photography projects carried out in contact with suffering − the artist asserts − are always very difficult to gestate. I think that only by feeling the victims’ pain can one convey this suffering decently.”

Perhaps for many people, inquiring into the sources of other people’s pain may not always be worthy of the least reverence or appreciation in terms of aesthetics or symbolic consummation. Hence that quite a few turn their backs on the wealth of alienating realities and nourish their own miseries in the liberating and propitiatory abundance of the light, of the tic of no responsibility. Fortunately, there are artists like Gervasio Sánchez, who channel the semic chain work-subjectivity-pain as the catalyst of an idea that goes beyond the limit of the specific, which is always impoverishing and morbid, and that, on the contrary, is summarized in the expansion of the work of art towards more laudable and humane territories. All these photographs, taken between 1998 and 2010 in countries like Chile, Argentina, Peru, Colombia, El Salvador, Guatemala, Iraq, Cambodia, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Spain, make it possible to write history based on sources with different positions and locations, and which are less cynical and accommodating.

In the epilogue of this representational endeavor, the artist tells us: “I see so much pain that I come to a sad conclusion: my work barely describes an intimate part of the drama of the “disappeared”. It is almost like a tear in a great river of silence, despair and dignity.”

-

View of Gervasio Sánchez’s exhibition “Desaparecidos” at the MUSAC, January - June, 2011. Photograph courtesy of MUSAC. Vista de la exposición de Gervasio Sánchez “Desaparecidos” en MUSAC, enero - junio, 2011. Fotografía cortesía MUSAC.

View of Gervasio Sánchez’s exhibition “Desaparecidos” at the MUSAC, January - June, 2011. Photograph courtesy of MUSAC. Vista de la exposición de Gervasio Sánchez “Desaparecidos” en MUSAC, enero - junio, 2011. Fotografía cortesía MUSAC. -

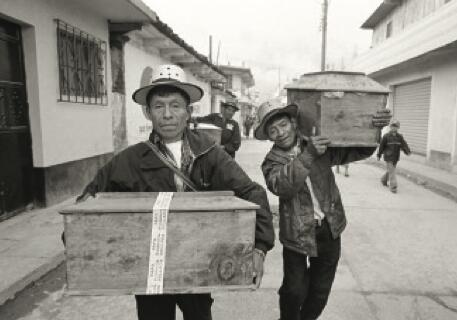

Peasants walk carrying the coffins containing the remains of his loved ones, identified two decades after their disappearances. Nebaj (Guatemala). B/N Photograph. Dimensions 100 x 140 cm. Courtesy of the author. Campesinos caminan con los ataúdes con los restos de sus seres queridos identificados dos décadas después de sus desapariciones.

Peasants walk carrying the coffins containing the remains of his loved ones, identified two decades after their disappearances. Nebaj (Guatemala). B/N Photograph. Dimensions 100 x 140 cm. Courtesy of the author. Campesinos caminan con los ataúdes con los restos de sus seres queridos identificados dos décadas después de sus desapariciones.

Nebaj (Guatemala). Febrero 2009. Fotografía b/n baritada. Dimensiones 100 x 140 cm. -

1984-26. Several mothers and wives of Srebrenica victims cry before the beginning of the memorial ceremony. Potocari (Bosnia-Herzegovina), July, 2010. Varias madres y esposas de víctimas de Srebrenica lloran antes del inicio de la ceremonia fúnebre. Potocari (Bosnia- Herzegovina), julio de 2010

1984-26. Several mothers and wives of Srebrenica victims cry before the beginning of the memorial ceremony. Potocari (Bosnia-Herzegovina), July, 2010. Varias madres y esposas de víctimas de Srebrenica lloran antes del inicio de la ceremonia fúnebre. Potocari (Bosnia- Herzegovina), julio de 2010 -

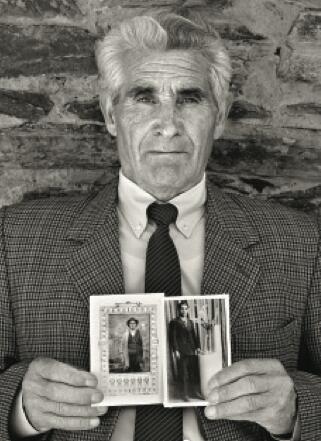

Laureano Marcos (1933) holds portraits of his father, Higinio Marcos, and brother Feliciano Marcos, executed in 1936 and since missing. Destriana, León (Spain)). 22 May 2010. Digital B/W Photograph. Dimensions 69 x 96 cm. Courtesy of the author. Laureano Marcos (1933) muestra los retratos de su padre, Higinio Marcos, y de su hermano Feliciano Marcos, ejecutados y desaparecidos en 1936. Destriana, León (España).

Laureano Marcos (1933) holds portraits of his father, Higinio Marcos, and brother Feliciano Marcos, executed in 1936 and since missing. Destriana, León (Spain)). 22 May 2010. Digital B/W Photograph. Dimensions 69 x 96 cm. Courtesy of the author. Laureano Marcos (1933) muestra los retratos de su padre, Higinio Marcos, y de su hermano Feliciano Marcos, ejecutados y desaparecidos en 1936. Destriana, León (España).

22 mayo 2010. Fotografía b/n digital. Dimensiones 69 x 96 cm. Cortesía del autor. -

Memorial Potocari (Bosnia-Herzegovina). July 2005. B/W Photograph. Dimensions 100 x 140 cm. Courtesy of the author. Memorial Potocari (Bosnia-Herzegovina). Julio 2005. Fotografía b/n baritada. Dimensiones 100 x 140 cm. Cortesía del autor.

Memorial Potocari (Bosnia-Herzegovina). July 2005. B/W Photograph. Dimensions 100 x 140 cm. Courtesy of the author. Memorial Potocari (Bosnia-Herzegovina). Julio 2005. Fotografía b/n baritada. Dimensiones 100 x 140 cm. Cortesía del autor. -

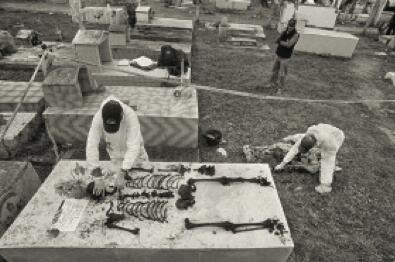

Exhumation at Puerto Nuevo. Departamento de Magdalena (Colombia), January 2010. B/W Photograph. Dimensions 100 x 140 cm. Courtesy of the author. Exhumación en Puerto Nuevo. Departamento de Magdalena (Colombia), Enero 2010. Fotografía b/n baritada. Dimensiones 100 x 140 cm. Cortesía del autor.

Exhumation at Puerto Nuevo. Departamento de Magdalena (Colombia), January 2010. B/W Photograph. Dimensions 100 x 140 cm. Courtesy of the author. Exhumación en Puerto Nuevo. Departamento de Magdalena (Colombia), Enero 2010. Fotografía b/n baritada. Dimensiones 100 x 140 cm. Cortesía del autor. -

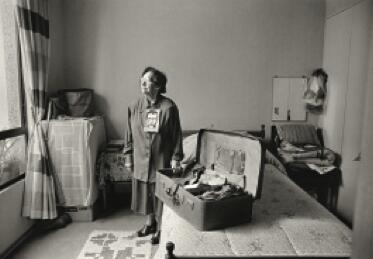

Anita Rojas with her son's Alfredo Rojas' suitcase. Missing March 4, 1975 Santiago de Chile (Chile), March 2000. B/W Photograph. Dimensions 69 x 96 cm. Courtesy of the author. Anita Rojas con la maleta de su hijo Alfredo Rojas, desaparecido el 4 de marzo de 1975. Santiago de Chile (Chile), Marzo 2000. Fotografía b/n baritada. Dimensiones 69 x 96 cm. Cortesía del autor.

Anita Rojas with her son's Alfredo Rojas' suitcase. Missing March 4, 1975 Santiago de Chile (Chile), March 2000. B/W Photograph. Dimensions 69 x 96 cm. Courtesy of the author. Anita Rojas con la maleta de su hijo Alfredo Rojas, desaparecido el 4 de marzo de 1975. Santiago de Chile (Chile), Marzo 2000. Fotografía b/n baritada. Dimensiones 69 x 96 cm. Cortesía del autor.