_“Paulo Bruscky—Art is Our Last Hope”_, at the Bronx Museum of the Arts, New York

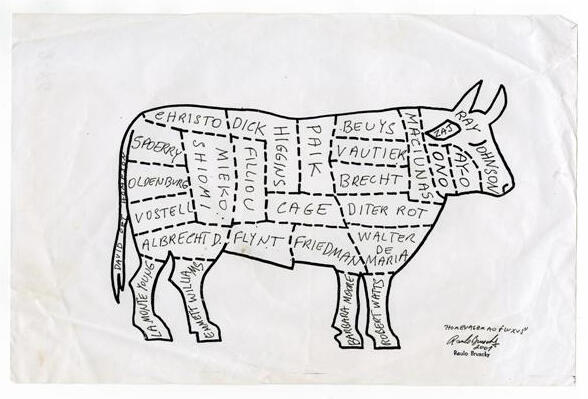

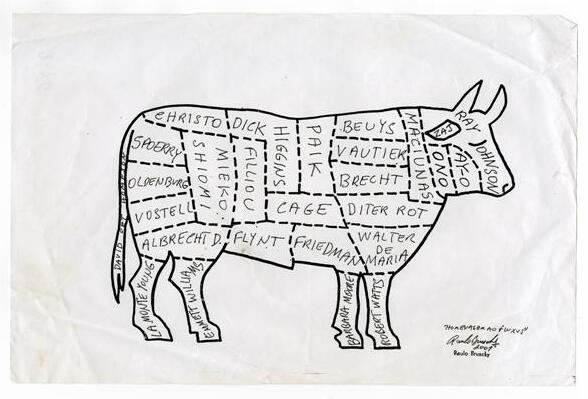

The Bronx Museum of Arts is Presenting “Paulo Bruscky—Art is Our Last Hope”, the first solo exhibition of work the Brazilian artist, who has played a critical role in bringing major artistic movements—including Fluxus, mail art, and performance art—to Brazil from the time he began working in Recife in the aftermath of the military coup of 1964.

He has also served as one of the most active and engaged voices representing Brazil in the global dialogue surrounding these movements. “Art is Our Last Hope” will feature 140 works made between 1971 and 2011 in a range of forms, including sculpture, performance documentation, mail art, and photography. The exhibition, organized by Sergio Bessa, Director of Curatorial and Education Programs at The Bronx Museum, will be on view through February 9, 2014.

Like many artists of his generation, Bruscky’s work reflects the increasingly repressive environment imposed on Brazilian civil society as indicated by the elimination of humanities courses in universities around the country, and the persecution of intellectuals, artists, student and union leaders. Despite this backdrop of widespread paranoia, Bruscky went on to develop a courageous body of work based largely on audience participation and the dissemination of messages through postcards, newspapers ads, and billboards.

Following the 1964 coup, Recife was seen as a hub for students and labor activists who sought to inform peasants about their rights, and the area soon became a major focus of military intervention. Amidst this dire situation, art for Bruscky became “the last hope,” as he stoically claimed in a public artwork—an arena for provocation and for exposing the absurdities of the political and social circumstances.

In stark contrast with the clean aesthetics of the Concrete Art movement of the 1950s and

60s, Bruscky sought to create a form of art that could represent the atmosphere in Brazil under military rule. He did this by turning his eyes to the street and to the daily reality of common people, using his work to address the anonymity and impoverishment of the individual in the urban landscape and countering that experience with humor and linguistic wit. Despite being one of Brazil’s most important contemporary conceptual artists, Bruscky has earned his living working for a local hospital for the entirety of his career.

While this daytime occupation could have been an obstacle to his artistic practice, in reality it allowed him the freedom to pursue his artistic interests independently of external pressures. Moreover, this medical environment inspired Bruscky to produce some of his most stirring works, leading to experimentations with electroencephalogram, electrocardiogram, and X-Ray machines. Bruscky’s ongoing interest in medical equipment has led him to poetically explore the relationship between body and machine through a variety of media.

“Paulo Bruscky makes work that engages everyone, particularly those left out of the global arts dialogue,” said Sergio Bessa. “We have two important works by him in our permanent collection. Interestingly, in 1982, while living in New York on a Guggenheim Fellowship, Bruscky sent one of his Xerox books to our curators, who added it to our collection. I believe he sent us the piece because he saw the connections between our mission and his work, and three decades later, we’re excited to introduce him to our audiences.”

Highlights of the exhibition include:

*Bruscky’s performance works were often inspired by Recife itself, where the artist would wander through the streets following an amorphous path defined by his experience of the urban environment. Indicative of this process was his 1973 work “Stop Art”, for which the artist staged a ribbon-cutting ceremony on a public bridge. Bruscky documented cars coming to a stop in a growing line that remained stagnant for 15 minutes (until the ribbon was finally broken by an impatient pedestrian), toying with urban dwellers’ expectations of city rituals and willingness to remain docile during events that were perceived to be “official.” A video of this event will be featured in the exhibition.

*As an extension of the Situationist movement that flourished in Paris in the late 1960s, in his piece “What is Art? What is it for?” Bruscky wandered around downtown Recife wearing a sandwich board with those questions printed on it. This work will be documented with several images in the exhibition.

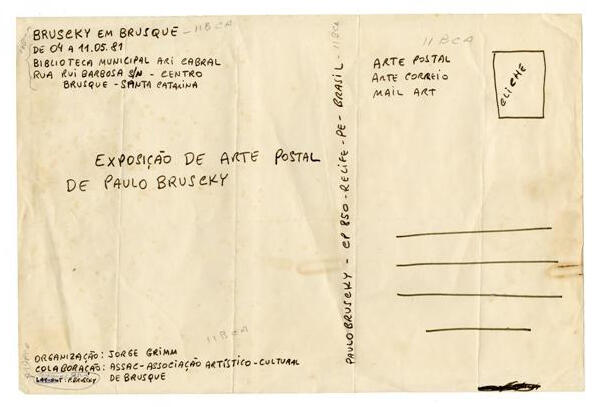

* For our missing ones, a collaged postcard from 1986 that features the faces of three people who went missing under the military regime in Recife, exemplifies Bruscky’s pioneering role in the mail art movement. By mailing cards like these across the globe, Bruscky turned his artworks into political tools that allowed him to develop an international network of people who were aware of the persecution and infringements of civil liberty that the artist and his contemporaries were experiencing in Recife.

*Several pieces in the exhibition illustrate Bruscky’s ongoing interest in using his own body as fodder for his art work, an area of exploration related to his longtime employment in a Recife hospital. Bio-graphy, from 2010, is a box containing all of the artist’s medical records dating back to his birth. “Art is Our Last” Hope will be accompanied by a new monograph on the artist by Adolfo Montejo Navas which will be released in a tri-lingual edition (Portuguese, Spanish, and English) by Distributed Art Publishers.