Di Pascuale, Mandrile, Castiñeira and Chalub

Museo Municipal Genaro Pérez, Córdoba

With the opening of the exhibitions of works by Lucas Di Pascuale, Cecilia Mandrile, Romina Castiñeira and Luli Chalub, Córdoba’s Gnaro Pérez Museum, which lodges an important local painting collection, implemented an interesting exchange between the pioneering painters in its permanent collection and some of the most refreshing referents of the new generation.

Lucas Di Pascuale (1968) is a mid-career artist who has found a balance between gallery exhibitions and research over the course of his career. We are faced with a case of family exhibitionism which, far from the self-reference that some present-day artists subject us to, inquires into his family universe through a mixed media using objects and intimate and domestic settings to manipulate photographs. Di Pascuale, an aesthete from his very early works, opens up for visitors a network of semantic possibilities resorting to an installation format. His story is, ultimately, the same as that of many Argentineans marked by a past of political violence. Starting with the title itself, Yerba mala ( Bad seed) is a stark series of works operating as a tunnel that connects politics, history, and personal experiences. Thus the artist succeeds in producing an impact on each visitor, questioning and disturbing him/her.

Cecilia Mandrile (1969) Due to her unceasing international career, she achieves a universal language that moves away from Di Pascuale’s historiographic references asserting the importance of the gaze, as accurately pointed out in the wonderful catalogue text written by Federico Falco. With a load of latent anguish, the passage of time and the time of transit mark the nomadic oeuvre of an artist eclipsed by fragility and by a lacerating nocturnality, where the face of lies combines with the interior intimacy of her dolls. The latter constitute the most painful demonstration of the vital calendar in motion. The photographs and the exotic praxinoscopes are especially noteworthy among the array of elements displayed in the museum galleries.

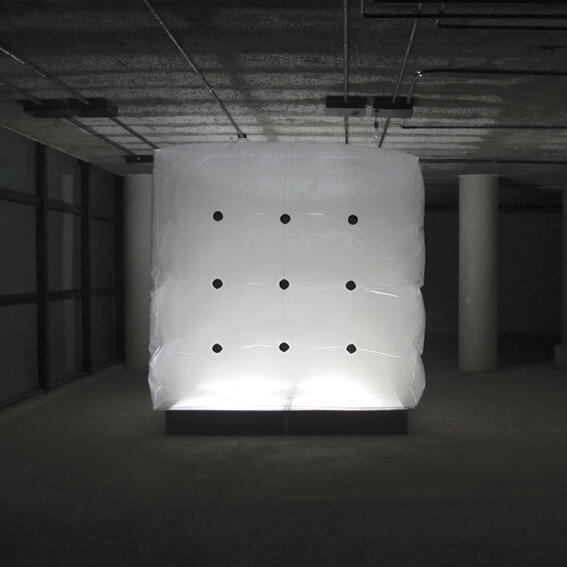

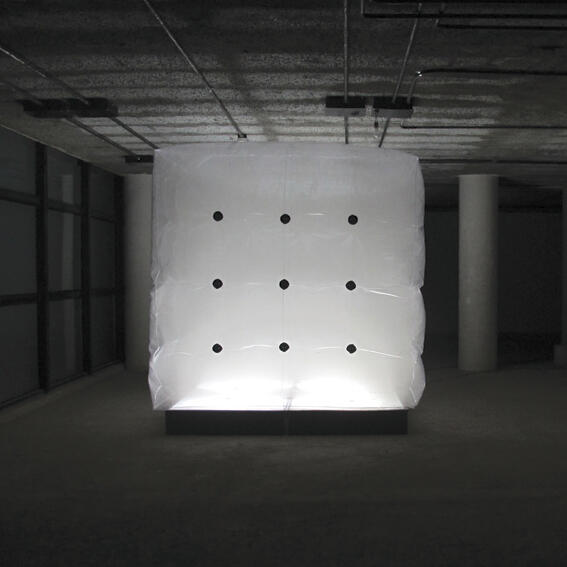

Romina Castiñeira (1985) presents her work Espacio – vacío, a comfortable way of addressing her quandaries from a conceptualism on which F5 has been pressed. The metrics of nothingness that she proposes through a piece defeated by the fatigue of representing the unrepresentable, renders visible the existence of the non-existent; it indicates that nothingness exists, that it is there. And she does so resorting to materials with medical reminiscences, with artificial characteristics. Castiñeira is not afraid of the unexpected aesthetics of synthetic asceticism when she addresses those abstractions which have accompanied humanity from the time of the Greeks to the present.

Luli Chalub (1967) features some of her recent works in a platform especially devoted to her by the museum. Unlike the artists surveyed at the same time, Chalub focuses on the trace, on the simple and determined gesture. Her pieces of an eminently visual nature seem to hide all the punk will of childhood. As in the case of the Old Masters, each face, each gesture is a mask. Her figures are ski masks that hide surfaces and liberate thoughts. Chalub does not paint, she writes in hieroglyphs in a synthetic and iconic way.

-

espacio vacio, 2,20 x 2,20 m., año 2012, Espacio Sobremonte

espacio vacio, 2,20 x 2,20 m., año 2012, Espacio Sobremonte

700 micron PVC, 4 transillumined bases with metal structure covered in backlight type tarpaulin. 1⁄2 hp. Turbine.Smoke machine. Electronic control board and timers system, 2,20 x 2,20 m. Courtesy of the artist

PVC de 700 micrones. 4 Bases trans iluminadas de estructura metálica y revestidas en lona tipo backlight. Turbina de 1⁄2 hp. Máquina de humo. Sistema de plaquetas y timers electrónicos, 2,20 x 2,20 m. Cortesía de la artista.

-

Espacio vacío (detalle), 2,20x2,20m., año 2012, Espacio Sobremonte

Espacio vacío (detalle), 2,20x2,20m., año 2012, Espacio Sobremonte

700 micron PVC, 4 transillumined bases with metal structure covered in backlight type tarpaulin. 1⁄2 hp. Turbine.Smoke machine. Electronic control board and timers system, 2,20 x 2,20 m. Courtesy of the artist

PVC de 700 micrones. 4 Bases trans iluminadas de estructura metálica y revestidas en lona tipo backlight. Turbina de 1⁄2 hp. Máquina de humo. Sistema de plaquetas y timers electrónicos, 2,20 x 2,20 m. Cortesía de la artista.

-

Espacio vacío, 2,20 x 2,20 m., año 2013, Museo Genaro Pérez, Córdoba, Argentina

Espacio vacío, 2,20 x 2,20 m., año 2013, Museo Genaro Pérez, Córdoba, Argentina

700 micron PVC, 4 transillumined bases with metal structure covered in backlight type tarpaulin. 1⁄2 hp. Turbine.Smoke machine. Electronic control board and timers system, 2,20 x 2,20 m. Courtesy of the artist

PVC de 700 micrones. 4 Bases trans iluminadas de estructura metálica y revestidas en lona tipo backlight. Turbina de 1⁄2 hp. Máquina de humo. Sistema de plaquetas y timers electrónicos, 2,20 x 2,20 m. Cortesía de la artista.

-

Espacio vacío, 2,20 x 2,20 m., año 2012, Espacio Sobremonte

Espacio vacío, 2,20 x 2,20 m., año 2012, Espacio Sobremonte

700 micron PVC, 4 transillumined bases with metal structure covered in backlight type tarpaulin. 1⁄2 hp. Turbine.Smoke machine. Electronic control board and timers system, 2,20 x 2,20 m. Courtesy of the artist

PVC de 700 micrones. 4 Bases trans iluminadas de estructura metálica y revestidas en lona tipo backlight. Turbina de 1⁄2 hp. Máquina de humo. Sistema de plaquetas y timers electrónicos, 2,20 x 2,20 m. Cortesía de la artista.