Fernando Bryce

Drawing, Mimetic Analysis, and the Archive*

Historical truth, for him, is not what has happened; it is what we judge to have happened. Jorge Luis Borges, “Pierre Menard: Author of the Quijote”

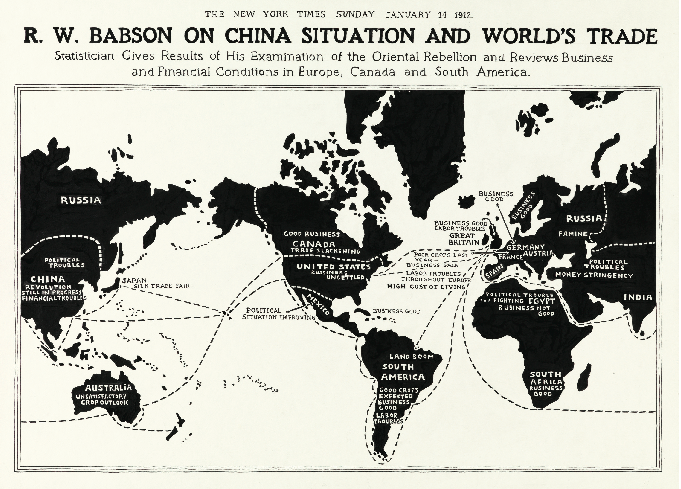

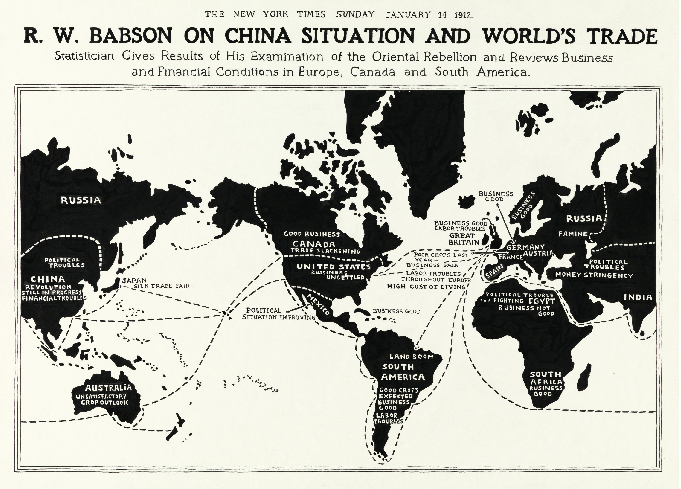

Recently a number of commentators have noted the renewed interest in drawing among contemporary artists, and the tendency towards “labor-intensive” works on paper – many of them figurative - that draw attention to the skill of the artist.i A number of these artists – among them Andrea Bowers, Fernando Bryce, Sam Durant, D.L. Alvarez, and others- render news photographs and printed matter related to political activism and historic events. Unlike the ́Pictures ́ generation that emerged from the seminal exhibition of the same name curated by Douglas Crimp in 1977, artists today are not reflecting on the “death of the author.” Recent drawings do not replicate photomechanically produced images through appropriation, nor do they create an illusion of seamless reproduction of pictorial sources. Rather, this work suggests that artists are turning to drawing – with its associations of immediacy and closeness to the artist’s process - as a critical practice that engages both artist and viewer in a process of reflection about history and memory. It is the very distinction between a drawing and a mechanically reproduced image that raises questions about common assumptions photographs and documents to objective and accurate records of events. Nonetheless, this focus on the mediated aspects of images is something both the ́Pictures ́ generation and artists like Bryce share.

Fernando Bryce (Lima, 1965, lives in Berlin and Lima) stands out among his contemporaries for his intellectual breadth, rigor, and his focus on drawing practice. His project entails critical reflection on the intersections between visual, editorial and exhibition cultures, the functions of archives, and the implications of all of these for historical memory. Since the mid-1990s he has been conducting research at various archives and libraries, locating printed matter that in most cases can be viewed as a form of propaganda, related to pedagogic, artistic, commercial, and diplomatic exchanges, as well as by political parties, and revolutionary groups, which he renders in drawing series.

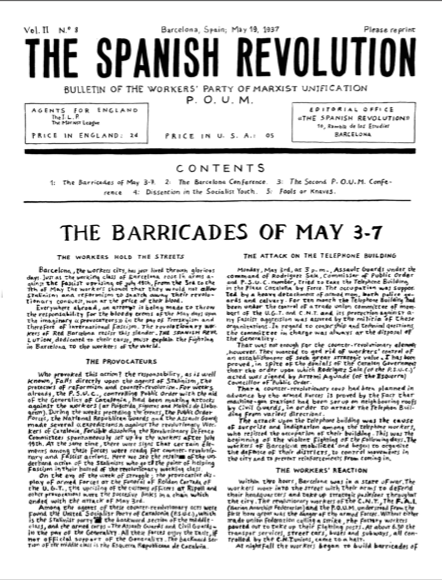

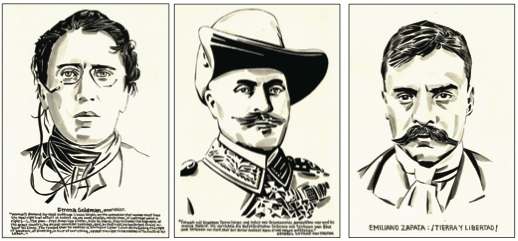

The Spanish Revolution and The Spanish Civil War (both 2003) are part of this broader project of recuperating and investigating archival materials originating from periods of political upheaval, and whose historical traces have either been distorted or occluded.ii The Spanish Revolution is a series of twenty-one ink on paper drawings of the covers of the English edition of the dissident Marxist party Partit Obrer d’ Unificació Marxista newspaper of the same name which was published in Barcelona between 1936 and June 1937. He renders book covers, pages from magazines, pamphlets, and calendars, as well as portraits of political and military figures in The Spanish War, a series of one hundred and twenty seven ink on paper drawings. (Fig. 1) The printed matter Bryce represents in this latter series was produced by leftist groups and political parties that were loyal to the Spanish Republican government. (Fig. 2) It also includes a small number of drawings of materials produced by groups supporting the right-wing military uprising led by General Francisco Franco, including his allies -Nazi Germany and Mussolini’s Italy. (Fig. 3) Bryce calls his working method “mimetic analysis” to indicate that there is an ongoing process of reflection that emerges during the selection, production and reception process. This performative aspect of his project might be understood through Diana Taylor’s formulation of embodied actions, “reiterative acts” and “ways of knowing” through which one can recuperate historical memories which have been suppressed or defined by hegemonic groups.iii This is the case of Spain, where during Franco’s 40-year dictatorship, the Republic was demonized and its history erased.

The response of the viewer is part of this ongoing critical process. For Bryce, drawing allows him to “homogenize the images.”iv In so doing their content, and the potential relationships between them, come into sharper relief. Bryce was drawn to the POUM newspapers, since they are rare traces of the party, which was attacked by both the Communist Party (then largely following a Stalinist line) and the Spanish Republican government during the Civil War— leading to what has been called a civil war within a civil war in Republican Barcelona in May 1937.v (Fig. 4 The Spanish Revolution) In rendering this series, Bryce wanted to “approach aspects that have more or less been silenced” of the Spanish Civil War and reflect upon the varied political positions within the Spanish Popular Front, from democratic republic to social revolution.vi

Although there are materials from both sides in the series The Spanish War, the artist in no way means to suggest equivalence between the two. In fact, the proportions -far fewer pro-Franco materials are included than Republican ones -are intended by the artist to indicate his own position towards the political ideologies represented in the images.vii Thus, Bryce’s selections, juxtapositions and the proportional number of images he selects are part of a new open archive.viii Although the work does have a “partisan position” his aim is to place the images in a new context that allows for individual reflection on the “constructed and mediated condition of these images.” Rendering materials printed on different types of paper, or in varying conditions of preservation, using a single media - ink on paper - and creating a new context for them outside of their original archive does homogenize them. And in placing materials produced by Anarchist groups from the Republican side with those generated by partisans of General Franco’s right-wing coup, Bryce also signals the mingling in the archive of materials produced for drastically different ends, leading to a process of equivalence and de-contextualization.

However, the beautiful array of brushwork leads one to consider Bryce’s technical prowess, the painstaking effort involved in rendering each drawing, the specific typefaces, or the lights and shadows of the illustrations. Moments of doubt, transcription errors, stops and starts at times interrupt the flow of ink and appear as black condensations covering part of a text. In other cases, pentimenti appear as penciled text visible beneath the ink. Signaling Bryce’s working process and its manual, labor- intensive quality, these rare moments alert the viewer to the fact that these are not in fact homogeneous pages. These traces of Bryce’s hand, like those of the everyday lives of those who produced and handled these magazines, pamphlets and newspapers, and of historical events that we try to understand through these materials, suggest their transitory, elusive, and mediated nature. The research process for The Spanish War – locating and selecting the images, reading about the period and producing the drawings took one year. Bryce’s selective practice of creating a repertoire of images through drawing underscores the fact that we often take for granted the conditions that led to the formation of a particular archive, systematic, fortuitous, or repressive, for example. Why did some documents survive, being considered worthy of conservation, and not others? Who controls access to them? How are they catalogued? Such questions are not only academic. In Spain today, for instance, family members of those persecuted under Franco for their loyalty to the Republican government – imprisoned, killed, buried in unknown mass graves – are still unable to access archival collections that could shed light on their relatives’ fates.ix These questions also extend to scholarly research processes, what conditions or biases lead a historian to find or to choose to publish a given document and not others? The archival document, assumed by some to be a direct link to the past, is highly mediated then through a series of factors that come into play prior to its location, classification, and subsequently through the ways in which it is interpreted and re- contextualized by historians. Bryce draws attention to documents that in many cases lie buried in archives, or are only consulted by specialists, yet their presentation in museum or gallery settings, as well as reproduction in books or magazines, expands their audience to a limited extent.

One might also ask what prior knowledge about the events that appear in the images is necessary. Bryce seems to regard this as an open question, and in the materials he renders, or through their translated titles on exhibition labels, text and image are available to the viewer-reader. The unfamiliarity of many viewers with the sources Bryce draws on, and the ways in which he groups materials thematically or chronologically, create the conditions for varied levels of access and interpretation. Indeed, Bryce calls for individual response and reflection, which is integral to his own archival working process, rather than creating work that is explanatory, dogmatic or illustrative.

This focus on individual subjectivity, analysis and interpretation clearly follows theoretical discussions that have demonstrated that a photograph or the contents of an archive are never neutral or objective documents. Rather, these materials are products of the sedimentation of particular hierarchies of value regarding what is and is not worthy of conservation, products of political upheaval, efforts to preserve personal, national or institutional memories. Bryce’s production leads us to examine the ways in which archival documents are viewed as transparent historical evidence and the degree to which our own selection and interpretation of them plays a role in their reception.

** Miriam Basilio, Assistant Professor of Art History and Museum Studies, New York University

* I would like to thank Fernando Bryce, Jose Luis Blondet, Taína Caragol and Gabriela Rangel.

i Laura Hoptman. Drawing Now: Eight Propositions (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2002).

ii In the case of both series of drawings, the archival materials are housed at the Ibero-Amerikanische Institut in Berlin.

iii Diana Taylor. The Archive and the Repertoire. Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas. (Durham and London, Duke University Press, 2003), pp. 2-3.

iv E-mail to the author, email September 11, 2004.

v See Helen Graham. The Spanish Republic at War, 1936-1939. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

vi E-mail to the author dated September 11, 2004.

vii 30 out of the total 117 drawings in The Spanish War are after pro-Franco propaganda materials

viii “Conversation” [interview of Fernando Bryce by Helena Tatay. In Gustavo Buntinx, Kevin Power, Rodrigo Quijano, and Helena Tatay, Fernando Bryce (Barcelona: Fundació Antoni Tàpies, 2005), pp. 371-385, p. 374.

ix Spain’s Ley de Memoria Histórica, passed in December 2007, includes norms to facilitate accessibility to archives that contain information regarding political repression, killings, and disappearances.

Figures: 1 Drawing that reads “Madrid” 2 Drawing that reads “Palabras de “Pasionaria”” 3 Drawing that read “España Roja” 4 Drawing that reads “The Barricadas of May 3-7”

Profile:

Fernando Bryce was born in 1965 in Lima, Peru. After pursuing studies in Visual Arts at the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, and with Leslie Lee in Lima, he perfected his training in France, at the University of Paris and the École des Beaux Arts, under Christian Boltanski. In 2000, he was awarded the Prize of the National Biennial of Lima, and in he was the recipient of a scholarship from the Deutsche Akademie Rom Villa Máximo. For 2009. Especially noteworthy among his numerous solo exhibitions are “Visión de la Pintura Occidental”, Galerie Barbara Thumm, Berlin (2002); “Turismo/El Dorado - Alemania 98” (2002), Künstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin; Raum für Aktuelle Kunst Luzern, Switzerland (2003); Konstmuseet Malmö, Sweden (2005); Tàpies Foundation, Barcelona, Spain (2005). His works are represented in the following public collections: The Museum of Modern Art, MoMA, New York, U.S.A.; The Tate Modern, London, United Kingdom; The Carnegie Museum, Pittsburgh, U.S.A; Kunstmuseum St. Gallen, Switzerland; VAC Collection, Valencia, Spain; ARCO Collection, Madrid, Spain; Burger Collection, Zürich/Hong Kong; The Tom Patchett Collection, Santa Monica, U.S.A.; Berezdivin Collection, Puerto Rico; Pablo and Tinta Henning Collection, Houston, U.S.A. Works of his are also included in private collections in Europe, the United States and Latin America.