Gabriel Orozco

Centre Pompidou, Paris

Gabriel Orozco − Jalapa, Mexico 1962 − makes the issue of understanding and interpreting art through the limits a central theme in his work. Each of his acts of expression and personal reaction to a specific environment, and each movement he makes within a medium, a language or a place, always seems to go directly into this central problem. His work is always out of place and in its place. It is almost impossible to describe it, for the simple reason that there is nothing we can call “his style”. Each work is the plastic realization of a different idea or a different wish, and it responds to an impulse originating in something he has seen, in a place or a situation. His oeuvre is characterized by the diversity of the techniques he employs − drawing, photography, video, sculpture, installation − developed freely, smoothly and with ease.

Four institutions have collaborated to produce this exceptional exhibition: the Centre Pompidou in Paris, MoMA New York, the Basel Kunstmuseum and London’s Tate Moderm, which are showing a certain number of works in common. However, each museum proposes to develop, in close collaboration with the artist, a singular aspect of his work. Occupying the Southern Gallery of the Centre Pompidou − which represents the traveling exhibition’s third stopover − with its large glass win- dows, the installation elaborated by Orozco proposes a totally new device based on the notion of the workshop. Without any commentaries or names, the works presented with simplicity show the moment of creation. For the occasion, the artist, who currently divides his time between New York, Mexico and Paris, involved himself strongly in the conception of the itinerary of the eighty works, many of which had never before been shown in France. In a semi-darkness, the sculpture-objects are placed in two segments of parallel lines of the same length. −one composed by the work tables for the small objects, and another one formed by the voluminous works, on the floor. On the wall, perpendicular to those two lines, is a linear presentation of photographs, drawings, collages, and paintings. Emblematic works, less known or more recent works, such as the sculptures executed with trunks found in the Mexican desert.

In many of his works, Orozco confronts the familiar with the strange. Recontextualized, reconfigured and manipulated found objects include toilet paper streamers as they form a whirlwind in the blades of a ceiling fan; an elevator resting on the museum floor; a group of interlaced bicycles, a chessboard featuring only horse figures to play. Interest in the organic, the circle, expansion and the cosmos is present in the series “Atomists” - 1996-, photographs of sportsman excerpted from British news- papers on which the artist has printed circular motifs. These forms are produced by the enlargement of individual Ben-Day dots in the printing process to create the monochrome ellipti- cal and circular compositions on the images.

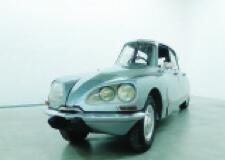

As the nomad he is, Orozco does not appear to request faithfulness or a home from any specific culture or nationality, but he does not detach himself from or situate himself above every culture or nationality; rather, he assumes a commitment with several of them. In almost every case, he insists on producing works which are neither universal nor regional, but which can involve multiple contexts and readings. My hands are my heart, in which the artist breaks up a piece of terra-cotta and gives it the shape of a heart, has a meaning as a metaphor symbolizing the connection with the land, which might well be that of Mexico or that of any other place. Orozco does not divert the original function of the project: he reinterprets it. In La DS, a Citroën DS car whose central part has been cut off later to join together the two ends, as in Elevator, a dismantled elevator cabin reduced to human dimensions, the artist performs the reduction of an everyday space in whose relationship with objects there is an attitude that tends to revert the predictable order attributed to these, an attitude that disturbs the viewer, who cannot visualize its habitual function.

Mixing art and reality, disrupting the boundary between the art object and the environment, where magic and transformation materialize before the viewer, Orozco renders this encounter an unforgettable, simple and touching moment.