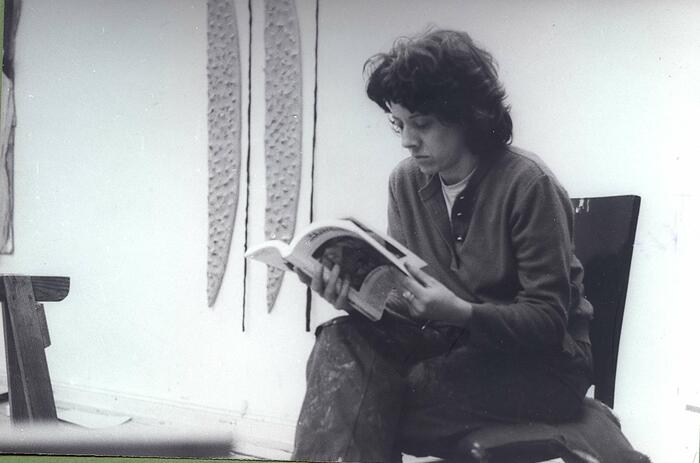

LIGIA D'ANDREA: VISUAL POETRY THAT ESCAPES FROM TWO-DIMENSIONALITY (part 2)

From drawing to installations

Ligia D'Andrea mentions minimalism in her installations and also the artist's books she makes, as three-dimensional plastic supports. The next question was: How does Ligia's interest in the conceptual language of installation relate to her passion, which is the language of drawing? For Ligia, installation exists as an extension of drawing. But first she recalls where it all came from.

"I come from a generation whose time only presented three options: painting, sculpture and printmaking. Then photography appeared. And the language of installation appeared only in the 70's in Brazil, when I was still living there." Ligia came to identify with Jannis Kounellis, and with Joseph Beuys, that of social sculpture and all the criticism against decorative art. Despite the classic divisions of Western art into categories, for the artist what connects everything is drawing. Even at school she spent her time drawing lines of all kinds, particularly in her history and geography classes.

For me, drawing is the writing that one learns at school in preparation to write. The abc for me is a drawing, a drawing with a connotation. First you learn to draw, see any child first scribbles. Doodling is our first language of understanding, of symbols. From there you go to writing, which is a domestication of drawing, so that you understand that A is A, to give sound and meaning. [4]

I see it this way, I love to make artist's books, to graph in the drawings I make, to copy texts from other writers. I love copying texts, I do it to rest. Like they made us write as punishment in school: "I mustn't do that...". That repetition of the same sentence, of copying texts. From writing texts I got the theme of the occupation of space.

Later in her studies, Ligia D'Andrea took minimalism as a sign of her works to the intervention of space: she began to draw with black threads like taut lines in the exhibition hall, occupying the space with her drawing, making it a territory. This was in the 1970s at the school of arts in Berlin (Germany). "I thus encountered a conceptual metaphor that for me was innovative."

It can now be understood why for our artist, to speak of installations is in essence to speak of drawing. Installation is the language in which she found it possible to draw with threads in three dimensions. In this sense, she also maintains that drawing is a writing that occupies space.

Drawing for me is two-dimensional space. Installations are three-dimensional space. Drawing is a language like writing. The stroke of the pencil or the nib on the paper, I transformed it in the 70's in space with the threads. And there I detached myself a little from the merely formal theme.

Multiplying perspectives with installations

In the 80's she had begun to rehearse different types of installations, being "Canto del Silencio" (Berlin, 1986) and "Evolución y olvido" (Barcelona, 1988) two referential works that explored austerity and silence, inviting to reflect both on the colonial relationship of slave labor and the extraction of natural resources in American territories, as well as on the effect of the advance of the industrialized world.

At this point, at the dawn of the 1990s, we find what could be called Ligia D'Andrea's spider-like becoming [5]. It is enough to see how the rooms she intervened with her ephemeral installations with threads looked like. "Projecció" will be the artist's first installation using black threads, still in the old continent, back in 1991. It is the work of a weaver, although she conceptualizes it more as a way of drawing three-dimensionally. The threads, which started from fixed points on the walls, intertwined in the middle, forming a transparent, visually hypnotic fabric that temporarily occupied the gallery space.

We may be tempted to make associations with current proposals by artists such as Tomás Saraceno, in the traveling exhibition "How to trap the universe in a spider's web" (Museo de Arte Moderno. Buenos Aires, April 2017), in which the artist organized the transfer from the jungle to the museum of 7,000 spiders, generating the conditions of temperature, dim light and appropriate ventilation, so that they would be weaving for six months inside a large room of the Museo de Arte Moderno. We had this type of work in mind when we talked about Ligia D'Andrea's spider-becoming, with the precursor installations she made in Europe in the early 1990s.

Ligia D'Andrea in the Bolivian context

Ligia D'Andrea's work began to be known in Bolivia in an embryonic period of contemporary art for the country, the 1990s. Roberto Valcárcel, in complicity with Gastón Ugalde, had initiated an important movement in the 80's in La Paz, with the famous artistic actions in public spaces, besides having participated in the Sao Paulo Biennial (BRA). While in Santa Cruz de la Sierra abstract art had begun to be known by the Santa Cruz artist Marcelo Callaú, the 90's represented for this city a big step towards the expansion of the traditional western categories of art, driven by an independent platform called "Artefacto" that took place in the Museum of History in 1996. It was conceived by five artists: Ejti Stih, Raquel Schwartz, Guido Bravo, Sol Mateo and Valcárcel himself. One of the principles of this platform consisted in vindicating the active character of the architectural space where the work of art takes place; another very important one was to consider the work of art as the possibility of giving new meanings to the existing things of the world.

Ligia D'Andrea's line of creative flight had led her to the language of installation, which brought her to Bolivia in 1993. In 1994 she presented the already historic installation and artist's book "Space and Interpretations", BHN Gallery, La Paz, this time weaving/drawing with red and black wool threads, managing to link the ceiling, walls and floor of the gallery. Valería Paz writes about this in the great book Bolivia: Los caminos de la escultura: "the groups of red and black threads formed planes that were transforming the space, projected from lines or fixed points, giving the impression of crossing it, forming multiple perspectives". (PAZ: 2009, p. 372). But in addition to forming a spatial geometry, the installation corresponded to Ligia D'Andrea's poetic parameters: material fragility of the threads, ephemeral character, minimalism, visual song in silence, in addition to the interweaving of planes with multiple meanings.

As we have anticipated, the artist also sought to make images from different contexts that coexist in these installations, which is why she included in the exhibition some tin masks fixed on the walls, representing the Supay China and the Devil, symbolizing the complementarity between masculine and feminine within the Andean culture, thus showing a curiosity for the symbols of the specific space.

It is worth noting that Ligia D'Andrea's work fits in perfectly with the minority movement that was taking place in Bolivia in those years. A movement that began to experiment with non-conventional means of expression, that revalued the elements of everyday life, in addition to some substantial aspects of pre-Hispanic art, and that rebelled against the commercial concept of art.

Epilogue

From the conversations we have had with Ligia I extract, by way of closing, some phrases that portray her work as an artist: "always trapped, fractioning the space to get out of the two-dimensional". I also remember the time she wrote to me when she arrived home after a long day: "I'm a little tired after a long day of running around, but it seems that when you are tired you become a little more lucid about the essential things, don't you?”

Meditating on her trajectory, she reflected aloud: "I think my brain has a thing for always thinking three-dimensionally. And trying to capture that three-dimensionality through a concept". And as for the procedure she has followed all her life to advance her work, she once told me something fantastic: "I'm always doing things, as one always does when one doesn't even know very well what one is doing, and that middle place without knowing is very comfortable for me: not having to say I'm going to do such and such a thing. It comes from where I am at that moment".

And as for an article I published this year generating several debates in the local scene, she sent me some lines that I treasured as accurate: "reflections out loud can create conflict zones, but without them we do not move".

I am left with the lesson that even more important than getting out of two-dimensionality in geometric and spatial terms, what Ligia D'Andrea has achieved with her works is to infect us with a will not to let ourselves be trapped by the two-dimensional in our ways of thinking and living. In this sense, even in the act of hanging two-dimensional paintings on the wall, Ligia D'Andrea spoke to us, in her last exhibition in Santa Cruz, of the corridors that can be opened to glimpse another world where all planes can meet, overlap, juxtapose, intercalate, conjugate, making the world a becoming, a communicating field. [6]

[4] Ibid

[5] Allusion to the concept of the becoming-animal proposed by Deleuze and Guattari in the 70's, and explained mainly in his work A Thousand Plateaus. 2nd volume of Capitalism and Schizophrenia.

[6] "The intelligence that does nothing but repair, breaks the complexity of the world into dissociated fragments, splits the problems. Consequently, the more multidimensional the problems become, the more inconceivable they become. Unable to consider the context and the planetary complex, intelligence becomes blind and irresponsible". (See, Edgar Morin, Uniting Knowledge. El desafío del siglo XXI. Plural editores, November 2000).