Leandro Katz

Henrique Faría Fine Art. New York

A small, exquisite exhibition of vintage photographs from the 1970s by Leandro Katz affords us a view of this little known body of work. The artist’s small gelatin silver prints feature a series of trees, waterfalls, and alphabets constructed with images of the moon. Katz’s photographic investigations are informed by his interest in man’s interaction with and perception of the natural environment. The title for the exhibition, Natural History, is an explicit reference to Pliny the Elder’s Naturalis Historia, an encyclopedic work on geography and natural phenomena.

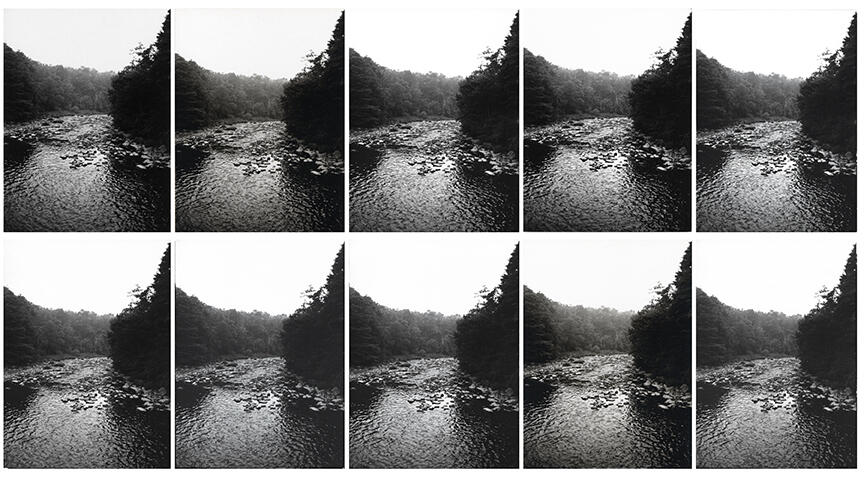

Spinning 1 (Fall), Spinning 2 (Winter), Spinning 3 (Spring), Spinning 4 (Summer), all from 1972-73, are the earliest works on view at Henrique Faria Fine Art. The series features thirty- six images taken while the artist moved as if spinning under the trees with his camera pointed at the treetops, capturing glimpses of the cloud formations and light in different seasons. The Spinning series, together with other photographs, effectively produces a certain spatial disorientation, effected, in this instance, by the radically uptilted view. Following Fall and Winter, Katz began time-lapse photographs of small waterfalls that he sought out on the back roads in New York, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania. In places no longer remembered, with the guidance of maps that are no longer in his archive, he photographed Indian Falls (10 seconds) of 1973 and The Fall (23 seconds) of 1975.

The earlier photographs feature ten shots of the same view taken every second for ten seconds, and the later ones, the same view taken every second for twenty-three seconds. In addition to locating sites suitable for his photographic purpos- es, the artist’s central concerns were expressed through the second by second sequencing that challenges the viewer to grasp the almost imperceptible changes in the movement of water captured in each frame.

Katz was clearly not inspired by the majestic falls of Niagara or Iguazu, on the border of Argentina and Brazil, or even Tequendama, in Colombia, which in the 19th-century attracted both North and South American landscape artists. If we fast forward, we recognize the differences between Katz’s encapsulation of an immediate experience in a private area and Olafur Eliasson’s grand, public art project of 2008, New York City Waterfalls. In contrast, Katz attempted to capture, in sequenced shots, a small body of water measurable in human scale, pro- portionate in size to its particular setting, and in constant flux like life itself.

The quiet, almost deadpan approach to photographing falls over a short sequence of time has an almost mesmerizing effect on the viewer. Subtle differences from print to print are enlivened by the compositional design in which they are mounted: some in circles (The Fall (4-second circle), 1977); others in stepped sequences (Jungle Falls, 1978); others on diagonals (The Fall (6-second diagonals), 1977).

The better-known works in this selection include the pho- tographs from the Lunar Alphabets series: The Genitive Eye, 1978-79; Phrase #2 - A Bellshaped Conjecture; and White Rushes Tied to a Cluster of Mulberry Shoots, both of 1979; and three studies. The project began in 1976 with two films, and continued into the mid ‘80s with photographs, drawings, and installa- tions. The photographs here feature phases of the moon in horizontal lines like phrases or sentences punctuated by a hyphen and/or a period, as in The Genitive Eye or paired with twenty seven letters, including an ñ from the Spanish alphabet, as in the three studies. The work is informed by Precolumbian art and his- tory, semiotics, and film. The structure of language defined by a lunar vocabulary strikes us as being at once both familiar and unfamiliar, and alternately near and far. Katz has successfully carried forward the Duchampian legacy, which in part takes a common, everyday object out of its familiar con- text and makes it something more.

We look forward to becoming acquainted with more pho- tographs from the 1970s in Katz’s archive, so we can better contextualize his art in that decade.