Leo Battistelli:

Attempting the impossible

Life makes no sense. That is why art exists. We are doomed to insist, to wish to remain, to persist through time, but our fate is to leave. We know this since childhood: in the future there will be a day when we will no longer be here. Although it makes no sense, life is an explosion of intensity. That intensity arises from the awareness of finitude: death is what makes it possible for each day to be worthwhile. What we are now, what we do, will never be repeated. Artists confront us with the beauty of life, with its naked power. But not all artists are capable of enjoying that happiness that enraptures us; not all artists know about the pleasure of an instant. One of those few artists who are aware of the power of the ephemeral is Leo Battistelli, who is capable of petrifying that which flows.

For two decades now, Battistelli has been attempting the impossible. Each work is a new challenge. He takes beauty in a state of incandescence as a starting point and goes beyond it. For Battistelli, beauty is not a visual or a formal harmony but a form of energy, an intensity that is as subtle as it is powerful, and that transforms things, relationships, and situations. Furthermore, his works are also talismans; that is, apotropaic objects: they turn evil away. Talismans defend us because they have the power to keep us away from horror. They drive it away (in Greek, apotrepein means, literally, “move away”). Evil cannot be destroyed: it is always there, lying in wait. But we can drive it away; we can take a break. We can laugh and sing. We can enjoy life until the end − that which will no longer be driven away −comes. Battistelli works in this frequency: intensity in a sublime state.

In Dávida everything tends towards that beauty which is simultaneously moving and healing. Each of the works is a ritual mise-en-scene and also a pagan celebration. There is magic and enjoyment. There is pleasure and inwardness. Battistelli has been experimenting with ceramics for many years now. He went from working in his small home-workshop to doing so in large-scale production with the Verbano factory, in Santa Fe Province (Argentina), and later with the Luiz Salvador Ceramics Company in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. The choice of ceramics implies a process and a risk. The process is alchemical: it involves mixing water and clay and using that material to mold an object which emerges from the formless. That object (still fragile, imprecise) is then loaded into the kiln. In the firing process there is a strong component of unpredictability: one never knows beforehand − least of all when the works are large and very complex − if the piece achieved will actually resemble the dream piece.

Battistelli began his career speaking about memory. He continued with his ancestors’ legacy and exhibited glazed tiles and photographs documenting that process. Then he began to take an interest in water as an essential element, but above all as a flowing element: water is what passes. It may drag, destroy, devastate, but it also vivifies, nourishes, contains, caresses. He dreamed of a house in the water and petrified the flow in ceramics. The next step, at once hesitant and daring, was to bet on the alchemic: his work began to engage in a dialogue with the great masters of occult knowledge. Magic and the arcane formed part of his language, which was, however, increasingly clear and subtle.

In Dávida he took yet another step: he immersed himself with more passion than spirit of research in the world of African religions in Brazil, especially candomblé. His work is not an aesthetic translation of these rituals and beliefs; rather, he finds inspiration in them. Or more precisely, energy. Since Dávida is the exhibition of positive energy in its purest form. Each work is a talisman: the object that drives away evil; that protects us from harm.

It does not matter whether one is or is not familiar with the intricate world of candomblé, with its joyful gods, its divinations and promises. What is important in Dávida is that at the same time that each work holds a dialogue with the masters and mistresses of the terreiro; that it speaks of a spiritual world that coexists with our material world, it conjures a potency that dazzles us. There are no secrets in Battistelli’s very beautiful works; they show everything; they exhibit themselves openly, but we never manage to grasp all they are capable of expressing. It is as though they always had something more to say.

In a certain way, the aesthetic experience that Battistelli’s production gives rise to may also be understood, and perhaps even better, from other spiritual traditions: those of the I-Ching and the Tarot. Rather than religions, the Candomblé, the I-Ching and the Tarot are life experiences originating in spirituality. They are forms of reading the obscure signs that material experience provide us. Baudelaire used to say that we walk amidst cathedrals of symbols and that living consists in deciphering those symbols. Battistelli takes this deciphering to an extreme. We see everything, but as in a half-light: the beauty of discovery bewilders us and, paradoxically, it blinds us. For our own good, we see what we can.

Gota de agua (Water drop). Gota de sangre (Blood drop). Espuma (Foam) ¡Destilado de belleza! (Distilment of beauty!) Fuego y piedras de trueno (Fire and thunder stones) La cura (The cure) La danza sin fin (The endless dance.) Hoguera (Bonfire) Such the titles that Battistelli gives to his works. They are guides, but they are also mantras: they are instruments that allow us to free the mind from the flow of negative images that torment us. Battistelli’s works have a powerful spiritual component, but they are not religious. At least they are not so in the traditional sense of the religious: as the space of subjection of the human to the divine, or of the individual to the collective. There is nothing that evokes or summons to subjection in Dávida. Quite on the contrary: everything speaks of liberation, of joy, of flowing, of fusing with the future’s formless becoming.

In Dávida, Battistelli goes from the white color (which characterized his earlier shows) to an overwhelming chromatic jubilation. They are the colors of the orixás, the tonal exuberance of the candomblé. Through color he signals the offering: to give thanks for what one has, for what one achieves, for having lived, for continuing to live. Just as in his former works white took formal elegance to the highest level of refinement, in his current pieces the potency of color conveys a tumultuous and delicate beauty that leads us to think that Batistelli is in possession of the secret of perfection.

Life makes no sense. Pain is a sad stab that can tear us to pieces. To make offerings, to give back to the universe part of the energy it provides us with, is a way of being just. Dávida is the offering that Battistelli presents to life. And that we share.

Leo Battistelli was born in 1972 in Rosario, Argentina. He has lived in Rio de Janeiro since 2007. He studied Fine Arts at the National University of Rosario and ceramics at Leo Tavella’s Atelier thanks to a scholarship from the National Endowment for the Arts and Santa Fe Province’s Culture Scholarship. Since 1993, he has engaged in sculpture, painting, installation, photography, design, and exhibition curatorship. He has produced his works in the Verbano Porcelain Factory since 2003, and since 2007 in Luiz Salvador Ceramics, Rio de Janeiro.

He has had solo and group shows in the Juan B. Castagnino Museum, Rosario; Federico J. Klemm Foundation, Buenos Aires; MACRO, Museum of Contemporary Art, Rosario; Malba, Fundación Costantini, Museum of Latin American Art-Buenos Aires; MoMA, Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Museum of Modern Art, Sao Paulo; Proa Foundation, Buenos Aires; Rojas Cultural Center (University of Buenos Aires), Buenos Aires; the Grand Hotel, Uzés, France; the Departments of Contemporary Art, Rosario; the Post Office Cultural Center, Rio de Janeiro; the Friends of Art Salon, Rosario; the Bernardino Rivadavia Cultural Center, Rosario; Galería Belleza y Felicidad, Buenos Aires; Museum of Contemporary Art, Misiones; Globo Network and Antonio Berni Gallery, both in Rio de Janeiro.

-

Faience and pigments, 48.6 x 48.6 in. Courtesy GC Estudio de Arte and the artist.

Faience and pigments, 48.6 x 48.6 in. Courtesy GC Estudio de Arte and the artist.

Piel gris rosé, 2010 – 2011. Fayenza y pigmentos, 123,5 x 123,5 cm. Cortesía: GC Estudio de Arte y el artista. -

Faience, porcelain. Courtesy GC Estudio de Arte and the artist.

Faience, porcelain. Courtesy GC Estudio de Arte and the artist.

La Cura, 2011. Fayenza, porcelana. Cortesía: GC Estudio de Arte y el artista. -

Water Drop, 2010 - 2011. China and pigments, 60 cm in diameter, 4 cm thick. Courtesy GC Estudio de Arte and the artist.

Water Drop, 2010 - 2011. China and pigments, 60 cm in diameter, 4 cm thick. Courtesy GC Estudio de Arte and the artist.

Gota de agua, 2010 - 2011. Loza y pigmentos, 60 cm de diámetro, 4 cm espesor. Cortesía: GC Estudio de Arte y el artista. -

Drop of Blood, 2010 - 2011. Faience and pigments, 60 cm in diameter, 7 cm thick. Courtesy GC Estudio de Arte and the artist.

Drop of Blood, 2010 - 2011. Faience and pigments, 60 cm in diameter, 7 cm thick. Courtesy GC Estudio de Arte and the artist.

Gota de sangre, 2010 - 2011.- Fayenza y pigmentos, 60 cm de diámetro, 7 cm de espesor. Cortesía: GC Estudio de Arte y el artista. -

Distilment of Beauty, 2011. Porcelain and sulfates, 31.5 x 21.6 x 7.8 in. Courtesy GC Estudio de Arte and the artist.

Distilment of Beauty, 2011. Porcelain and sulfates, 31.5 x 21.6 x 7.8 in. Courtesy GC Estudio de Arte and the artist.

Destilado de belleza- Porcelana y sulfatos, 80 x 55 x 20 cm. Cortesía: GC Estudio de Arte y el artista. -

Bonfire, 2011. Porcelain, faience, nylon, wood, 15.7 x 35.4 x 196.8 in. Courtesy GC Estudio de Arte and the artist.

Bonfire, 2011. Porcelain, faience, nylon, wood, 15.7 x 35.4 x 196.8 in. Courtesy GC Estudio de Arte and the artist.

Hoguera, 2011. Porcelana, fayenza, nylon, madera, 40 x 90 x 500 cm. Cortesía: GC Estudio de Arte y el artista. -

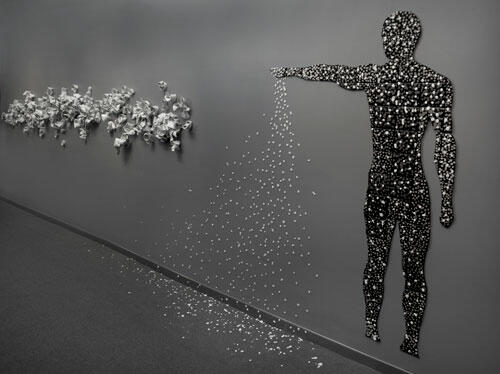

Courtesy GC Estudio de Arte and the artist.

Courtesy GC Estudio de Arte and the artist.

Vista de la exposición. Cortesía: GC Estudio de Arte y el artista. -

Courtesy the artist. Cortesía del artista.

Courtesy the artist. Cortesía del artista.