Olivier Debroise

MUAC, Mexico City

Olivier Debroise’s work, even if not exhibited, illustrates the polyvalent quality of writing, of the executer and of the reader, and at the moment of showing himself to the public he links together and unleashes something which is not pointed out anywhere in museography or in history; something which has more to do with the act of cracking a nut open than with eating it in different recipes. It coincides with the act of writing about it, because what might be said continues in that inertia of flows where the public, the writer, the reviewer, and the rest, join in. An archive is a fishing box. An open archive is the multiplicity of lines and hooks thrown into the sea. What would saying something about it, about his exhibition, be? Bait, perhaps.

This museum experience obliges the viewer to be under its norms and solidifies the raw material of the imaginary of the multi-headed creator. On the one hand, we are in the face of the researcher who speaks the language of the theatrical (aware that time is action), and investigates an exteriority which is not alien to the intimate, close to the immediacy of the journalistic and without losing the categories of the anthropologist. On the other hand, we are before the impassive sybarite whose order is at equal distance from pleasure, and which is at the same time, tangent to the more politicized art. The assemblage works as a reflection of a spirit which passes with a synthesizing capacity of its own in that timed surface par excellence which is cinema: it is so perceived in Un banquete en Tetlapayac (2000), meta-fiction of Que viva México, by S. Einsenstein (1930).

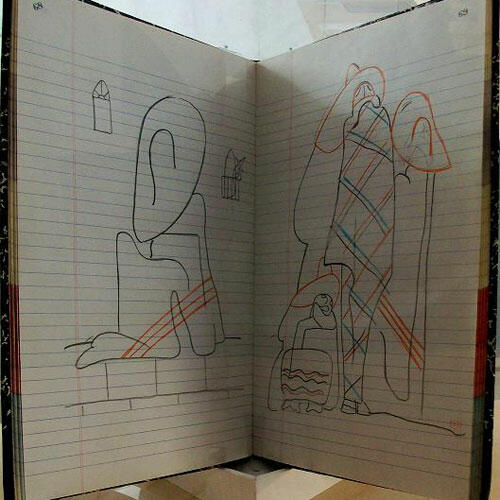

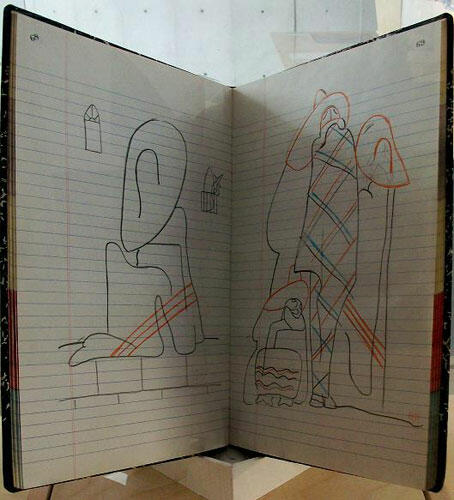

Through his work books, Debroise performs the role of a bridge on the abyss that often exists between the official-historical and the transgressing-fictional; he makes a pause in the point of convergence that he cannot elude in the flow of events of his production-investigation, but which becomes established in the different formats: notebooks, photographic records, video interviews, newspaper pages, recovered photographs. According to John Berger “There are no photographs that can be denied. All photographs are in the category of reality”, and it is precisely their quality of Cyclop who looks at his observer that detonates their links. The photographic image is a possible in-definition among thousands, of a time among thousands, whose dialectic property shall assemble in a present that no longer moves toward an equally undetermined place − the future − reactivating it with its halo of certainty which maintains it as an “adorable, visible, solid – yet untouchable enigma…” in the words of Octavio Paz. We look at the double morals in a documentary work: that which is, without being so, appearance, and that which is, without being, apparition.

The totality of exhibited works can be a tracing of the original map walked by Debroise, for if we put on the earphones and look at the monitor with “Un banquete…”, or if we listen to the words of Lola Álvarez Bravo, we will understand, didactically, a certain diagram which has made up its mind to become inserted in the historiography of Mexican Art. The archive opens the way –and therefore provides presence, and resonance – to the characters that in his scenario determined Debroise’s guidelines as a writer and as a simple witness of his own existence: this is perceived in the essays on María Izquierdo, T he red spirit is not dead, and Abraham Ángel and his time; whereas the books Crónicas de destrucciones and Lo peor sucede al atardecer, lying open on the table, also function from his astrological chart – exhibited on a wall-, giving testimony of something which even in death wants to survive in order to narrate, and that we are all, perhaps, prone to bite.

-

Page where he copies S. Einsestein’s drawings. Credit and courtesy/Crédito y cortesía: Fernando Caravajal. Cuaderno de trabajo de Olivier Debroise. Página donde copia los dibujos de S. Einsestein.

Page where he copies S. Einsestein’s drawings. Credit and courtesy/Crédito y cortesía: Fernando Caravajal. Cuaderno de trabajo de Olivier Debroise. Página donde copia los dibujos de S. Einsestein.