Regina Silveira

Heaven on Earth

In her current production, the Brazilian artist generates a true double eulogy of shadows and luminosity. Her most recent works are the territory hosting a critical, and at the same time nostalgic, exploration of a present that mixes the mentioned perceptive configurations, either through the fragmentation or the completion of the spatial enclaves she transforms. In the blurry boundaries of light and its absorption by penumbra, this international creator born in Porto Alegre, highlights the contrasts between saturation, clarity, brightness, transparency and opacity. For Silveira, the restitution of luminosity emerges as an emanation proper to the object or the topographic qualities of the environment she chooses to intervene...Worlds and bodies of light and shadows that conserve for themselves a last vestige of life.

Claudia Laudanno: - The coyote “paw prints” possess meanings of an anthropological and sociological character, in addition to incarnating social denouncement and constituting a test that you carried out based on an in situ study of the critical borders. Can you give us some clues for reading those works?

Regina Silveira: The first traces were the coyote tracks and paw prints, which I arranged along the walls of the entrance hall of the Museum of Contemporary Art in San Diego. I highlight, especially, Gone Wild (1996), entering into a dialogue with the decorative pattern of Dalmatians ́ spots, inlaid in the granite floor as an extension and component part of Architect Robert Venturi ́s design for the renovation of the museum. In this work, the relationship between the geographic region where the museum is located, on the border between San Diego and Tijuana, and the “coyotes”, individuals implicated in the illegal crossing of immigrants through this border, was not in the least an aesthetic or conceptual, apparently “innocent” reference.

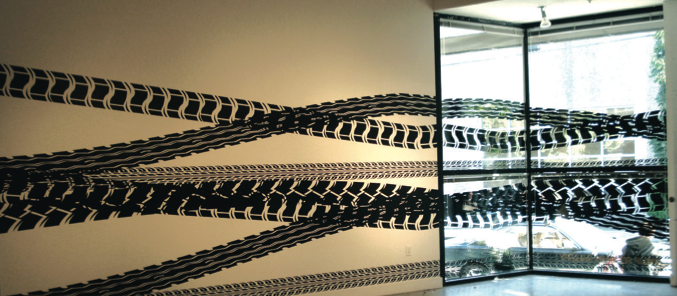

C.L: - There are other cognitive components in the open-ended series of the “tracks”. This seems to have led you to broaden the scope of your conceptual umbrella, or rather, your model. From your works with “prints” or animal traces, you gradually moved to the circumvolutions produced by car tires, always in black on white. Then we can affirm that there are two clearly differentiated bodies of works: those related to the shadows, from their ostensibly graphic planimetry, and the light installations or spatial environments.

R.S: - In the tracks, beyond the notions of disruption and the possibilities of graphic “pollution” similar to the one produced by “graffiti”, I am interested in data associated with time, understood as vestiges of an event, and with absence, which are characteristic of these kinds of images. In the years that followed, I broadened their paradigm, moving from the vinyl stickers featuring animals, to car-tire tracks and pathways, and from these to the agglomeration of self-adhesive vinyl stickers featuring human figures.

I consider I have been continually exploring this semantic and morphologic universe, from 1996 to the present, and I do not hesitate in affirming that these site specific interventions are the ones that currently respond to the work on shadows, always opposed to, or in direct polarity with, the interventions focused on light or in light projections, which have been and are a strong topic in the relationship of my work with architecture after the exhibition of Claraluz (1993), in the Banco do Brasil Cultural Center, in São Paulo.

C.L: - The passage or change in the scale of your images to reach a monumental scale was the result of a persistent feeling of horror vacui, an insistence on covering all the blank spaces. Which are the milestones and paradigmatic works representative of this manner of working?

R.S: - The plotted cut-outs of human figures arranged on fiberboard as insistent covering-blots, with a potential for covering practically any kind of surface and reach any scale, as is the case of the Irruption Series, had already been the subject of works meant to interact with specific architectures, which I performed, sequentially, in Brussels (La Mediátine, 1995), in Houston (MFA Houston, 2005), and later, on the external façade of the Taipei Fine Arts Museum, on the occasion of the 6th Taipei Biennial, in 2006, when the graphic image reached much more gigantic dimensions.

C.L: - The change in scale, the ductility in the use of different materials, and the Copernican turn from the utilization of a manual and myokinetic gesture to a digital production in your work entailed new formal and aesthetic solutions, in addition to the incorporation of seriality, modular repetition and sequences, trying to produce a regulated chaos. Then the work ceases to be a pure vestige, doesn’t it?

R.S: - That is to say, in all this trajectory, especially in what concerns the materials and scales employed, the radical change that allowed me to become bolder and adopt formats and dimensions compatible with the urban scale, or the large architectonic spaces, was the passage from a type of manual execution, generally painting, to a digital production. This also implied the end of the ephemeral in works that I painted exhaustively on walls, for them to last a short period of time, in order to pursue the potentiality of repetition implied in electronic matrices.

C.L: - The Catastrophe Theory and the Fractal Theory appear to have become established in your proposals for light installations. In them, light emerges as the referent of a breaking point, a censure, a hiatus, a rupture, based on the hyper-simulacrum you deliberately propose. The resplendent appearance and the excess of enveloping light may lead the spectators to a threshold of doubt, a lack of certainty, where they finally succeed in reformulating the functionality of the museum and its physicality. That is, you de-materialize buildings, many of them ancestral or huge architectonic masses.

R.S: - With respect to the family of architectonic interventions based on light and its projections, the most powerful examples of these were possibly certain works I made for Claraluz (Clearlight) and Lumen, at the Crystal Palace, Reina Sofía National Museum Art Center (Spain), and most recently, Ficciones (Fictions) (2007), in the exhibition spaces of the Vale do Rio Doce Museum in Vitória (Espirito Santo). After having made reference to the philosophic nature of light, of enlightenment, as well as to its opposite, the shadow, I would like to refer to an element that has been essential and common to those three productions, so decidedly determined by the physicality of the buildings where they were performed. The mentioned element or device is a “frozen visual narrative”, a kind of allegory through which I inserted a catastrophic idea into that architecture, no matter how stunning, or even beautiful its effect might be on the spectator’s mood.

C.L: - Lumen, Luminancia (Lumen/Luminance), Memoriazul (Bluememory) are examples of that regulated and programmed chaos and of a differential morphogenesis. Can you tell us how these works were received by the viewers?

R.S: - In the works Lumen and Luminancia, the two central pieces of Claraluz, simulation becomes established and is freely mimicked on the fragments of the building’s skylight, fictionally broken and later projected as luminous camouflage onto the walls of the same building, either as deposits or coatings in the space occupied by the safe in that institution which used to be a bank, and in a two-step narrative (two projections), which I later repeat on the glass roof of the Crystal Palace, in the work Memoriazul. This was another fiction featuring an imaginary catastrophic event: the breakage of hundreds of glass panels from the wonderful roof of the Crystal Palace, an event implicit in the new stained-glass roof printed on translucent vinyl and superimposed on the real panes of glass to make the roof appear literally broken and all its pieces deposited to form the digital carpet printed on plotter, whose surface was virtually destabilizing and vertiginous for the touring visitors.

C.L: - Recently, at the Museu do Vale do Rio Doce (Vitória) you exhibited Ficciones (Fictions), a completely imaginary and utopian interspace where you transform a large part of the museum premises into a vision of the infinite, of a firmament close to our terrestrial and human dimension. Your Entrecielo (Intersky) reduces the volume and physicality of the circumstantial enclave that shelters it. From an aesthetic point of view, how did you operate in order to obtain such results of progressive weightlessness and dematerialization?

R.S: - In Ficciones, whose title undoubtedly alludes to certain “elective affinities” I share with Borgean fictions, the catastrophic event is the virtual collapse of the solid walls that support the warehouses of the Museum, located at the side of a channel, like an arm of the sea against the sky; a sky like the Vitória sky, which is almost always blue, to give way to this resplendent and blinding light and to the simulation of a celestial space that penetrates the building’s inner space. My central idea in the work Entreceu (Intersky) was to create an interval in the architecture of the Museu do Vale do Rio Doce, dividing the premises into two parts barely supported by the backbone of the roof’s tie beams, with the aim of creating, in anyone roaming this sky without horizon, a total feeling of being suspended in space.