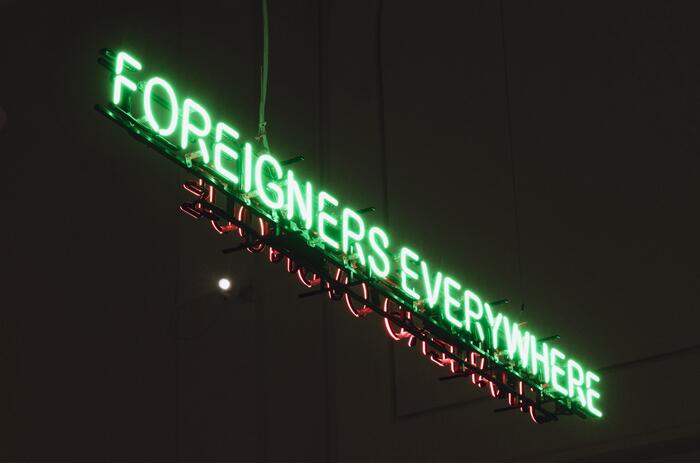

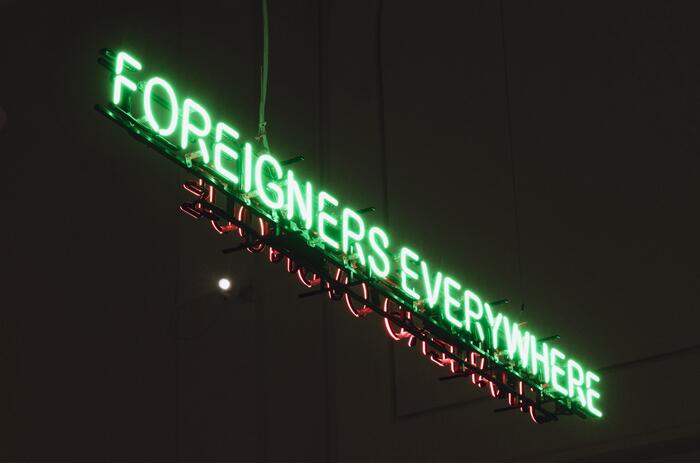

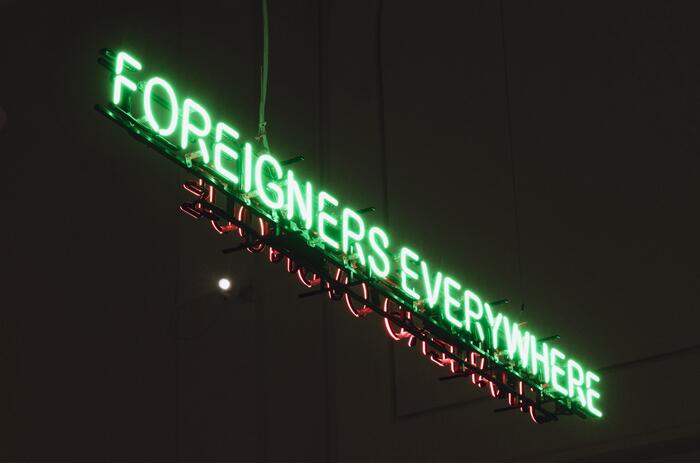

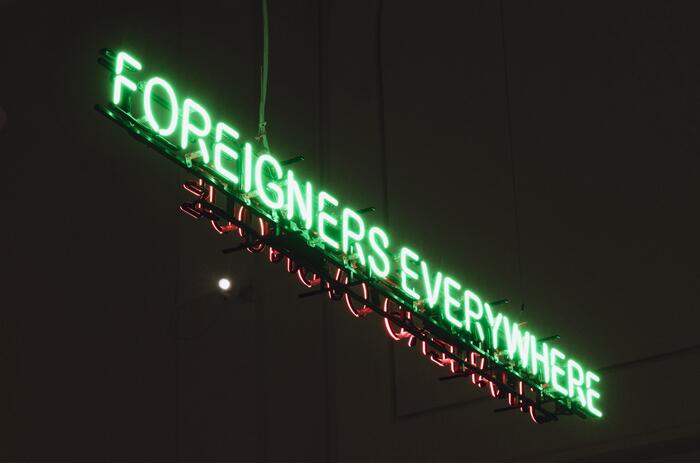

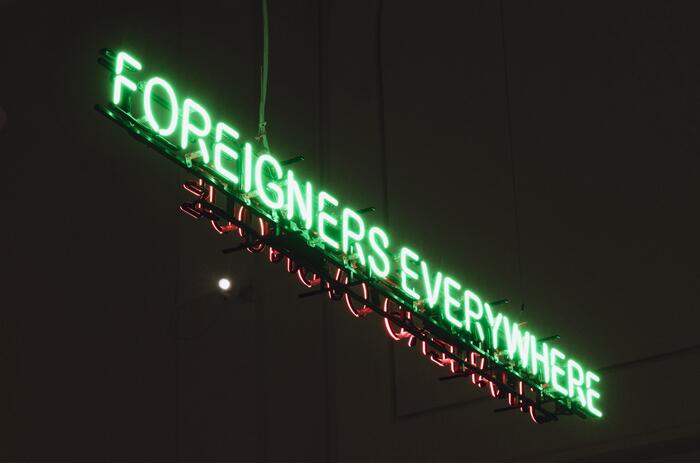

STORIES FROM THE SOUTH – THE VENICE BIENNALE TURNS AROUND ITS AXIS

Why highlight stories that often remain on the periphery of artistic discourse? Adriano Pedrosa justifies his curatorial decision with works by 331 artists -mostly from the global south- that open the way to powerful narratives. Finally, we see the axis being twisted. It is difficult to escape the white gaze, more so to move authentically through a Eurocentric space. Given this, the communicative reach of figuration serves to challenge the symbolic order of domination and destabilize the colonial project. The stories that are made explicit and the narratives of magic and everyday life help to recognize without revictimizing.

With a consciousness that does not categorize or hierarchize, the stories unfold through the spaces of the Arsenale and Giardini. Fundamental questions are posed: Which stories are to be exhibited and how are they formulated? The compositions, which range from detailed depictions of local stories to symbolically charged worldviews, expand the dialogue on micro-politics of change onto the global stage.

Because Adriano Pedrosa opened a portal: by highlighting stories from the Global South, the exhibition not only presented new narratives, but also provoked critical reflection on how these stories are told and, most importantly, who has the power to tell them.

Among the figurative works that inhabit the periphery of the art world, the Amazon stands out. Paintings such as those by Abel Rodríguez, trained among Nonuyas in the Colombian Amazon, reveal the profound biological and philosophical knowledge of these populations, through their detail and interconnectivity. The mural by the MAHKU collective (Movimento dos artistas Huni Kuin) on the façade of the central pavilion in the Giardini traces the myth of the kapewe pukeni and reflects on the (dis)connection between cultures. The drawings, patterns and colors of this mural make visible the rhythm of artistic but above all social conventions of a platform like the Biennale and of the general behavior of the art world. The mural seems to bring confluence in the face of conflict, and fluidity to confrontation.

-

MAHKU (Movimento dos Artistas Huni Kuin) Kapewe Pukeni [Bridgealligator], 2024. Site-specific installation 750 m260. Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte - La Biennale di Venezia, Stranieri Ovunque–Foreigners Everywhere 60th International Art Exhibition. Photo: Matteo de Mayda Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia.

-

MAHKU (Movimento dos Artistas Huni Kuin) Kapewe Pukeni [Bridgealligator], 2024. Site-specific installation 750 m260. Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte - La Biennale di Venezia, Stranieri Ovunque–Foreigners Everywhere 60th International Art Exhibition. Photo: Matteo de Mayda Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia.

-

MAHKU (Movimento dos Artistas Huni Kuin) Kapewe Pukeni [Bridgealligator], 2024. Site-specific installation 750 m260. Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte - La Biennale di Venezia, Stranieri Ovunque–Foreigners Everywhere 60th International Art Exhibition. Photo: Matteo de Mayda Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia.

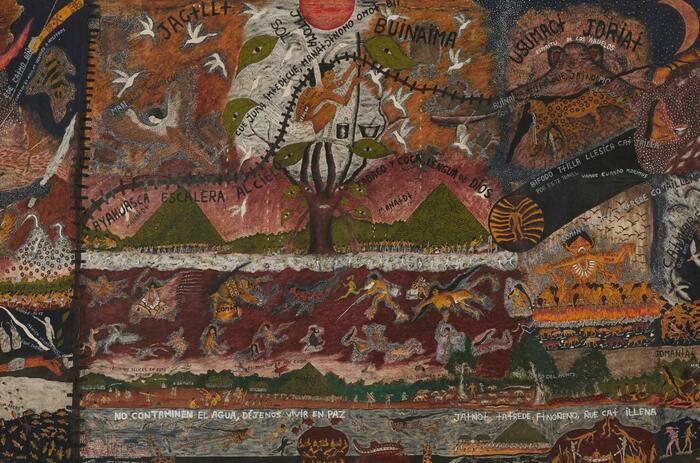

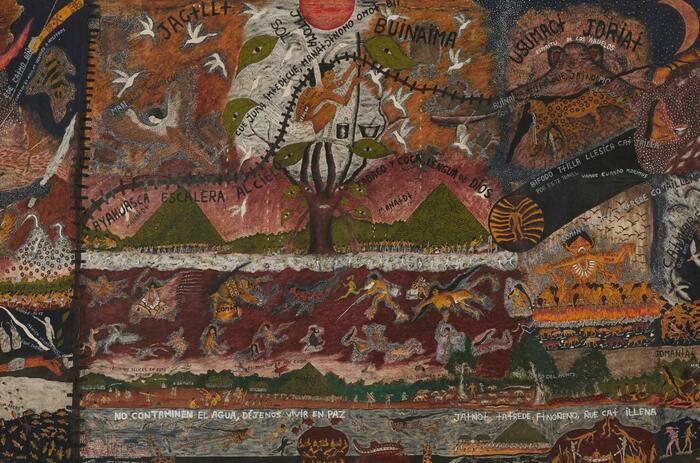

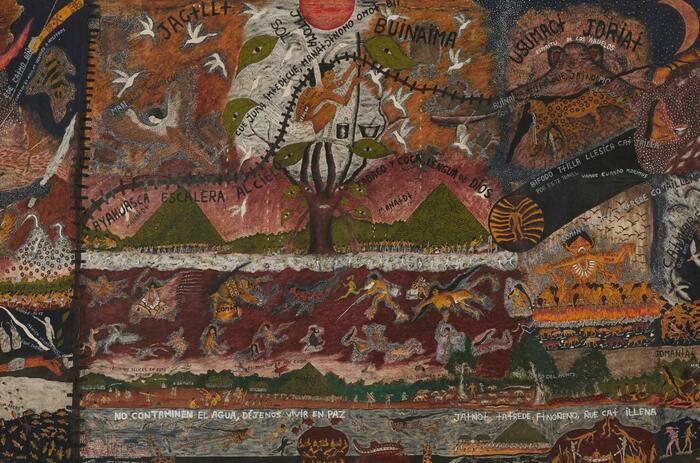

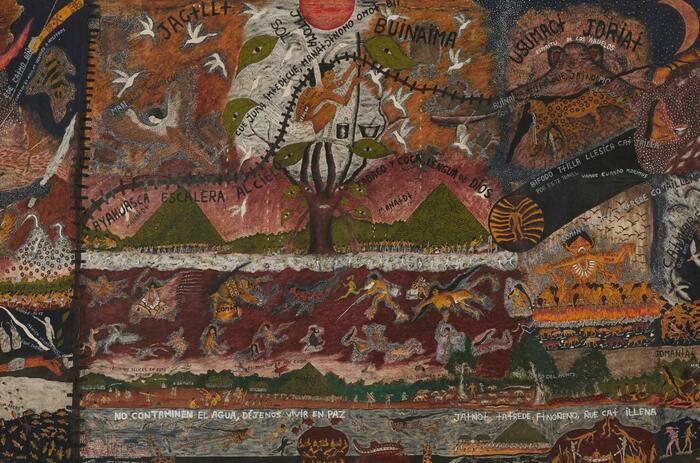

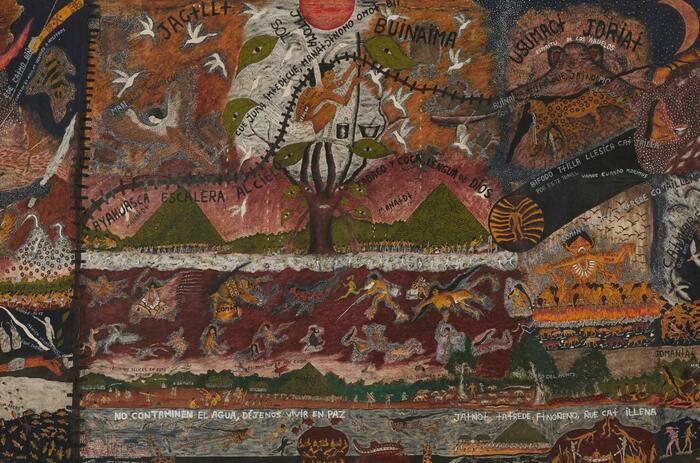

Yahuarcani's impressive paintings and compositions allude to the inhabited, memorial, conflictive, mythical, diverse, luminous and cyclical Uitoto territory. The narrative in these works is impossible to ignore, and they propose ways of living that promote synergy rather than rapture. From Haiti, Sénèque Obin (1893-1977) uses figuration to question and combat the label of the “primitive”. He articulates complex Haitian cultural events and illustrates powerful religious syncretism to show a personal and local perspective to the processes of modernity such as extractivism and homogenization.

-

Santiago Yahuarcani. 60th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere. Photo by: Andrea Avezzù. Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

-

Santiago Yahuarcani. 60th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere. Photo by: Andrea Avezzù. Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

-

Santiago Yahuarcani. 60th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere. Photo by: Andrea Avezzù. Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

-

Sénèque Obin. 60th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere. Photo by: Matteo de Mayda Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

-

Sénèque Obin. 60th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere. Photo by: Matteo de Mayda Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

The mural Diaspore, commissioned for the Biennale from Aravani Art Project (Bengalore, India), seeks to denaturalize the binary of gender and its consequent social constructions to express, in vibrant colors and multiple figurations, the possible expressions of gender and identity. La Chola Poblete, for her part, exhibits drawings and paintings where hybridization is the protagonist of the decolonizing process through a trans-indigenous lens. In her use of pop symbols, “modernized” iconographies of the Virgin, and Andean motifs, La Chola politicizes the personal beyond the politicization of art.

-

Aravani Art Project Diaspore, 2024 Mural painting 2715 × 600 cm. 60th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere. Photo by: Andrea Avezzù. Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

-

Aravani Art Project Diaspore, 2024 Mural painting 2715 × 600 cm. 60th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere. Photo by: Andrea Avezzù. Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

-

Aravani Art Project Diaspore, 2024 Mural painting 2715 × 600 cm. 60th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere. Photo by: Andrea Avezzù. Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

-

La Chola Poblete. 60th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere.

-

La Chola Poblete. 60th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere.

In Chile, the Bordadoras de la Isla Negra and the Arpilleristas use textiles as a means to narrate the daily life and challenges of a community. In the midst of the Pinochet dictatorship, the textiles offer an intimate vision of resistance and remembrance. The embroidery of the Bordadoras de la Isla Negra was stolen and disappeared in September 1973, after the Pinochet dictatorship took over the building that commissioned the work –the headquarters of the Third Session of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD III)– as its center of operations. The work reappeared in August 2019. The Arpilleristas documented women's experiences, emotions and struggles during the oppressive regime.

Bolivian photographer River Claure challenges traditional notions of documentary photography by infusing his images with elements of fiction and performativity. Claure reimagines photography as a dynamic medium that can tell stories beyond apparent reality. He questions the ways in which identities and landscapes are represented, specifically Andean mining communities, traversed by centuries of colonial extractivism. Exposing these stories implies playing, reimagining, rewriting the past and thinking about a new future. It is the revenge for those who had no voice.

Strangers Everywhere / Stranieri Ouvunque presents several layers of discourse, a kind of visual cacophony that challenges and re-configures the conversation. The figurative becomes a means to amplify, to tell a scenario of change. And this juxtaposition confronts crucial questions: Are these works limited to the popular? Do they reflect exoticist practices? Or do they redefine the value of the folkloric by integrating it into a scenario that has historically marginalized it? Beyond the politicization of art, the goal seems to be to reconfigure figurative “fashion” to empower a conversation that transcends the intellectual circle of art to a more mainstream, inclusive and global scale.

In this way, the representations of these narratives, often fragmented or silenced, become powerful tools for cultural participation and the construction of memory. These images, far from revictimizing, seek to recognize, heal and build bridges towards a new way of understanding history and the present.

Can the symbolic order of domination be truly destabilized? It is debatable, but what is undeniable is that a great step has been taken towards a necessary and urgent conversation.

May interest you

The voices of Latin American artists emerge strongly in this 2024 edition of the Venice Biennale. Claudia Alarcón, Julia Isídrez and Juana Marta Rodas, Ana Segovia, Frieda Toranzo Jaeger and Claudia Andújar lead viewers on a profound journey through their cultural heritage and unique artistic practices.

FIVE LATIN AMERICAN ARTISTS EXHIBITING FOR THE FIRST TIME AT THE VENICE BIENNALE

The voices of Latin American artists emerge strongly in this 2024 edition of the Venice Biennale. Claudia Alarcón, Julia Isídrez and Juana Marta Rodas, Ana Segovia, Frieda Toranzo Jaeger and Claudia Andújar lead viewers on a profound journey through their cultural heritage and unique artistic practices.

The voices of Latin American artists emerge strongly in this 2024 edition of the Venice Biennale. Claudia Alarcón, Julia Isídrez and Juana Marta Rodas, Ana Segovia, Frieda Toranzo Jaeger and Claudia Andújar lead viewers on a profound journey through their cultural heritage and unique artistic practices.

FIVE LATIN AMERICAN ARTISTS EXHIBITING FOR THE FIRST TIME AT THE VENICE BIENNALE

The voices of Latin American artists emerge strongly in this 2024 edition of the Venice Biennale. Claudia Alarcón, Julia Isídrez and Juana Marta Rodas, Ana Segovia, Frieda Toranzo Jaeger and Claudia Andújar lead viewers on a profound journey through their cultural heritage and unique artistic practices.

It takes an Island to Feel this Good is Darja Bajagić’s exhibition for the Montenegro pavilion at Venice Biennale 2024. Curated by Ana Simona Zelenović and organized by the Museum of Contemporary Art of Montenegro at the initiative of commissioner Vladislav Šćepanović, the exhibition will present a critical consideration of the culture of collective memory and the relationship to shared historical heritage.

ICONOGRAPHY, MEMORY AND HISTORY - THE MONTENEGRO PAVILION

It takes an Island to Feel this Good is Darja Bajagić’s exhibition for the Montenegro pavilion at Venice Biennale 2024. Curated by Ana Simona Zelenović and organized by the Museum of Contemporary Art of Montenegro at the initiative of commissioner Vladislav Šćepanović, the exhibition will present a critical consideration of the culture of collective memory and the relationship to shared historical heritage.

The monumental commission by British artist John Akomfrah RA for the 2024 Venice Biennale is a multi-layered exhibition which encourages visitors to experience the British Pavilion’s 19th century neoclassical building in a new way.

THE SOUNDS OF TIME – UNITED KINGDOM AT THE VENICE BIENNALE

The monumental commission by British artist John Akomfrah RA for the 2024 Venice Biennale is a multi-layered exhibition which encourages visitors to experience the British Pavilion’s 19th century neoclassical building in a new way.

Engaging with the theme of Adriano Pedrosa’s main exhibition for the Venice Biennale, Stranieri Ovunque—Foreigners Everywhere, Vlatka Horvat’s project for the Croatian Pavilion by the Means at Hand, curated by Antonia Majaca, exists as an accumulative exhibition of artworks by a wide-ranging group of international artists living as “foreigners,” reflecting on questions and urgencies of the diasporic experience.

CROATIAN PAVILION AT THE VENICE BIENNALE

Engaging with the theme of Adriano Pedrosa’s main exhibition for the Venice Biennale, Stranieri Ovunque—Foreigners Everywhere, Vlatka Horvat’s project for the Croatian Pavilion by the Means at Hand, curated by Antonia Majaca, exists as an accumulative exhibition of artworks by a wide-ranging group of international artists living as “foreigners,” reflecting on questions and urgencies of the diasporic experience.

The title of the 60th International Art Exhibition of the Biennale di Venezia, "Stranieri Ovunque", refers, in part, to foreignness as the inherent nature of the subject. Understood in this way, the national pavilions of Spain, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom exhibit artistic proposals that develop the theme of colonialism and reconstruct histories, remedy ties between identity and territory, and explore the dramatic plurality of this potent historical axis. That said, this review does not intend to unveil or unpack the most unjust transcendental truths, but merely to reflect on the musings of others.

THREE PAVILIONS AT BIENNALE 2024 THAT EXPLORE THEIR OWN COLONIAL PASTS

The title of the 60th International Art Exhibition of the Biennale di Venezia, "Stranieri Ovunque", refers, in part, to foreignness as the inherent nature of the subject. Understood in this way, the national pavilions of Spain, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom exhibit artistic proposals that develop the theme of colonialism and reconstruct histories, remedy ties between identity and territory, and explore the dramatic plurality of this potent historical axis. That said, this review does not intend to unveil or unpack the most unjust transcendental truths, but merely to reflect on the musings of others.

The Mongolian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale presents artist Ochirbold Ayurzana with the exhibition Discovering the Present from the Future. The proposal is curated by Oyuntuya Oyunjargal, the Cultural Envoy of Mongolia to Germany, and co-curated by Gregor Jansen, director of the Kunsthalle Düsseldorf in Germany.

OCHIRBOLD AYURZANA AT THE MONGOLIAN PAVILION

The Mongolian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale presents artist Ochirbold Ayurzana with the exhibition Discovering the Present from the Future. The proposal is curated by Oyuntuya Oyunjargal, the Cultural Envoy of Mongolia to Germany, and co-curated by Gregor Jansen, director of the Kunsthalle Düsseldorf in Germany.

Future Imaginaries, the collective exhibition at The Autry Museum of the American West, explores the rise of Futurism in contemporary Indigenous art as a means of enduring colonial trauma, creating alternative futures and advocating for Indigenous technologies in a more inclusive present and sustainable future.

FUTURE IMAGINARIES: INDIGENOUS ART, FASHION & TECHNOLOGY

Future Imaginaries, the collective exhibition at The Autry Museum of the American West, explores the rise of Futurism in contemporary Indigenous art as a means of enduring colonial trauma, creating alternative futures and advocating for Indigenous technologies in a more inclusive present and sustainable future.

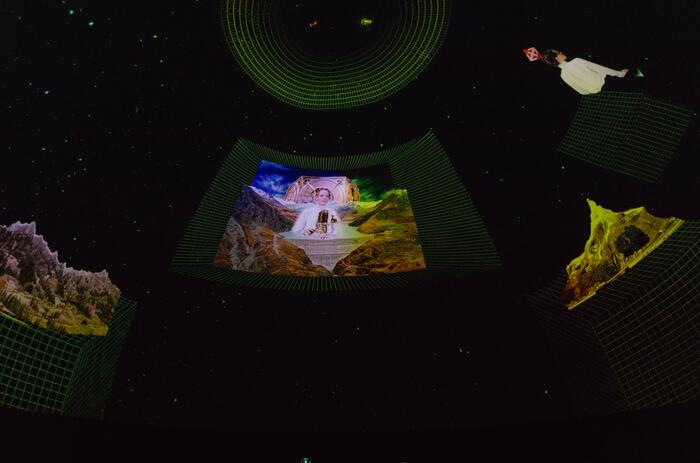

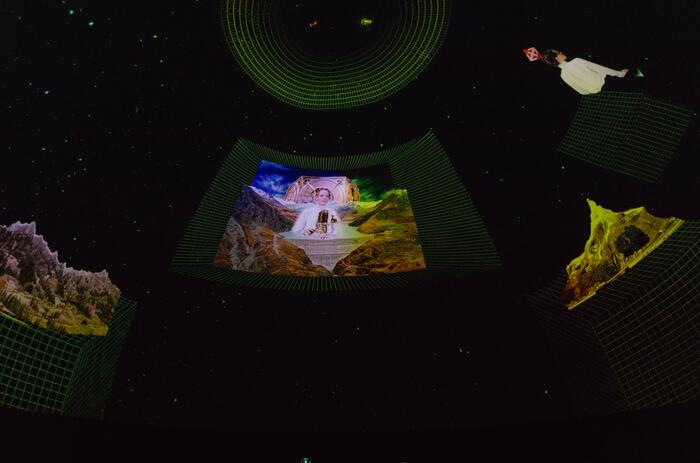

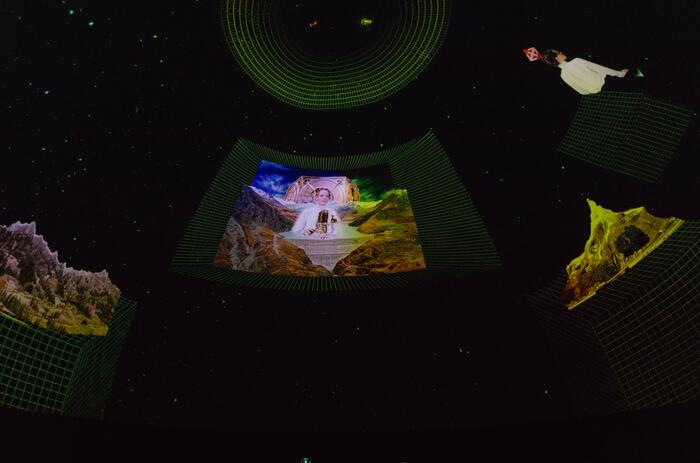

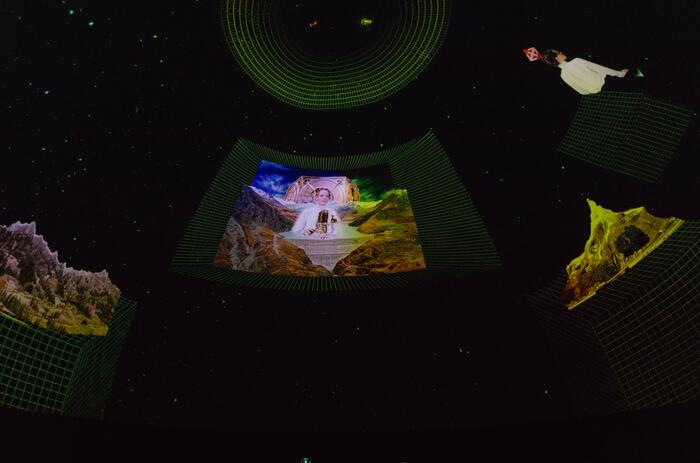

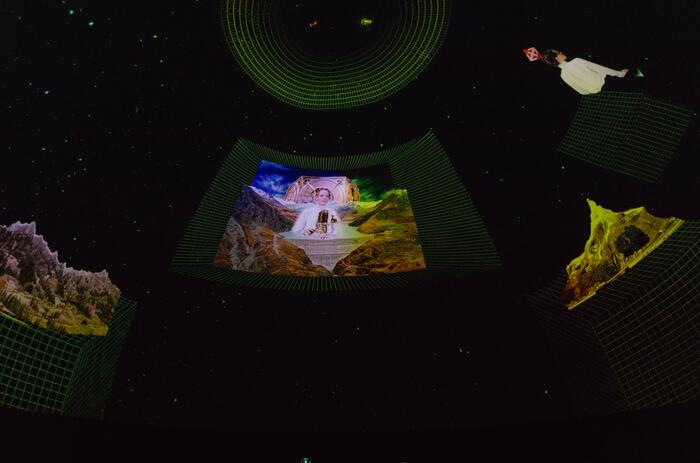

The Mexico Pavilion at the Venice Biennale 2024 proposes an immersive experience that invites the viewer to reflect on the act of migrating and its impact on identity and sense of belonging. As we marched away, we were always coming back is Erick Meyenberg's project curated by Tania Ragasol. It includes elements created in Mexico, Italy and Albania.

THE PATH OF MEMORIES – MEXICO AT THE BIENNALE

The Mexico Pavilion at the Venice Biennale 2024 proposes an immersive experience that invites the viewer to reflect on the act of migrating and its impact on identity and sense of belonging. As we marched away, we were always coming back is Erick Meyenberg's project curated by Tania Ragasol. It includes elements created in Mexico, Italy and Albania.

Disobedience Archive is a video archive project in constant transformation, linking artistic practices and political action. At the Venice Biennale exhibition, it takes the form of The Zoentrope, a pre-cinematographic machine that gives life to a space that generates new perspectives.

A GUIDE FOR PRACTICING DISOBEDIENCE

Disobedience Archive is a video archive project in constant transformation, linking artistic practices and political action. At the Venice Biennale exhibition, it takes the form of The Zoentrope, a pre-cinematographic machine that gives life to a space that generates new perspectives.

Crisis Galería announced the recent acquisition of the painting Cosmovisión Huitoto (2022) by the outstanding indigenous artist Santiago Yahuarcani by the Museum of Modern Art of New York (MoMA). This extraordinary large format work, made with natural dyes and acrylic paint on llanchama, is one of the largest produced by the artist with more than two meters high and four meters wide.

SANTIAGO YAHUARCANI ENTERS THE MoMA COLLECTION

Crisis Galería announced the recent acquisition of the painting Cosmovisión Huitoto (2022) by the outstanding indigenous artist Santiago Yahuarcani by the Museum of Modern Art of New York (MoMA). This extraordinary large format work, made with natural dyes and acrylic paint on llanchama, is one of the largest produced by the artist with more than two meters high and four meters wide.

The 2024 edition of the Venice Biennale is coming to an end. Stranieri Ovunque - Foreigners Everywhere, curated by Brazilian Adriano Pedrosa, offered a reflection through art about migration and borders, recurring themes in today's global discussion. Arte al Día was present to cover the 60th International Exhibition, not only to bring the work of more than 300 artists from almost 100 countries, but also to focus on the contribution of Latin American artists to the global scene, whose presence marked a high point in this edition.

VENICE BIENNALE 2024 – LATIN AMERICA EVERYWHERE

The 2024 edition of the Venice Biennale is coming to an end. Stranieri Ovunque - Foreigners Everywhere, curated by Brazilian Adriano Pedrosa, offered a reflection through art about migration and borders, recurring themes in today's global discussion. Arte al Día was present to cover the 60th International Exhibition, not only to bring the work of more than 300 artists from almost 100 countries, but also to focus on the contribution of Latin American artists to the global scene, whose presence marked a high point in this edition.

The Venice Biennale 2024 offers an exceptional platform for examining the challenges and opportunities facing the future. The pavilions of Japan, Germany, Switzerland and Hungary trace different forms of looking at and thinking about the world to come, projecting visions of the environment, equilibrium, adaptation, world order and, of course, collective memory.

POSSIBLE FUTURES AT THE VENICE BIENNALE

The Venice Biennale 2024 offers an exceptional platform for examining the challenges and opportunities facing the future. The pavilions of Japan, Germany, Switzerland and Hungary trace different forms of looking at and thinking about the world to come, projecting visions of the environment, equilibrium, adaptation, world order and, of course, collective memory.

The voices of Latin American artists emerge strongly in this 2024 edition of the Venice Biennale. Claudia Alarcón, Julia Isídrez and Juana Marta Rodas, Ana Segovia, Frieda Toranzo Jaeger and Claudia Andújar lead viewers on a profound journey through their cultural heritage and unique artistic practices.

FIVE LATIN AMERICAN ARTISTS EXHIBITING FOR THE FIRST TIME AT THE VENICE BIENNALE

The voices of Latin American artists emerge strongly in this 2024 edition of the Venice Biennale. Claudia Alarcón, Julia Isídrez and Juana Marta Rodas, Ana Segovia, Frieda Toranzo Jaeger and Claudia Andújar lead viewers on a profound journey through their cultural heritage and unique artistic practices.

It takes an Island to Feel this Good is Darja Bajagić’s exhibition for the Montenegro pavilion at Venice Biennale 2024. Curated by Ana Simona Zelenović and organized by the Museum of Contemporary Art of Montenegro at the initiative of commissioner Vladislav Šćepanović, the exhibition will present a critical consideration of the culture of collective memory and the relationship to shared historical heritage.

ICONOGRAPHY, MEMORY AND HISTORY - THE MONTENEGRO PAVILION

It takes an Island to Feel this Good is Darja Bajagić’s exhibition for the Montenegro pavilion at Venice Biennale 2024. Curated by Ana Simona Zelenović and organized by the Museum of Contemporary Art of Montenegro at the initiative of commissioner Vladislav Šćepanović, the exhibition will present a critical consideration of the culture of collective memory and the relationship to shared historical heritage.

The monumental commission by British artist John Akomfrah RA for the 2024 Venice Biennale is a multi-layered exhibition which encourages visitors to experience the British Pavilion’s 19th century neoclassical building in a new way.

THE SOUNDS OF TIME – UNITED KINGDOM AT THE VENICE BIENNALE

The monumental commission by British artist John Akomfrah RA for the 2024 Venice Biennale is a multi-layered exhibition which encourages visitors to experience the British Pavilion’s 19th century neoclassical building in a new way.

Engaging with the theme of Adriano Pedrosa’s main exhibition for the Venice Biennale, Stranieri Ovunque—Foreigners Everywhere, Vlatka Horvat’s project for the Croatian Pavilion by the Means at Hand, curated by Antonia Majaca, exists as an accumulative exhibition of artworks by a wide-ranging group of international artists living as “foreigners,” reflecting on questions and urgencies of the diasporic experience.

CROATIAN PAVILION AT THE VENICE BIENNALE

Engaging with the theme of Adriano Pedrosa’s main exhibition for the Venice Biennale, Stranieri Ovunque—Foreigners Everywhere, Vlatka Horvat’s project for the Croatian Pavilion by the Means at Hand, curated by Antonia Majaca, exists as an accumulative exhibition of artworks by a wide-ranging group of international artists living as “foreigners,” reflecting on questions and urgencies of the diasporic experience.

The title of the 60th International Art Exhibition of the Biennale di Venezia, "Stranieri Ovunque", refers, in part, to foreignness as the inherent nature of the subject. Understood in this way, the national pavilions of Spain, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom exhibit artistic proposals that develop the theme of colonialism and reconstruct histories, remedy ties between identity and territory, and explore the dramatic plurality of this potent historical axis. That said, this review does not intend to unveil or unpack the most unjust transcendental truths, but merely to reflect on the musings of others.

THREE PAVILIONS AT BIENNALE 2024 THAT EXPLORE THEIR OWN COLONIAL PASTS

The title of the 60th International Art Exhibition of the Biennale di Venezia, "Stranieri Ovunque", refers, in part, to foreignness as the inherent nature of the subject. Understood in this way, the national pavilions of Spain, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom exhibit artistic proposals that develop the theme of colonialism and reconstruct histories, remedy ties between identity and territory, and explore the dramatic plurality of this potent historical axis. That said, this review does not intend to unveil or unpack the most unjust transcendental truths, but merely to reflect on the musings of others.

The Mongolian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale presents artist Ochirbold Ayurzana with the exhibition Discovering the Present from the Future. The proposal is curated by Oyuntuya Oyunjargal, the Cultural Envoy of Mongolia to Germany, and co-curated by Gregor Jansen, director of the Kunsthalle Düsseldorf in Germany.

OCHIRBOLD AYURZANA AT THE MONGOLIAN PAVILION

The Mongolian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale presents artist Ochirbold Ayurzana with the exhibition Discovering the Present from the Future. The proposal is curated by Oyuntuya Oyunjargal, the Cultural Envoy of Mongolia to Germany, and co-curated by Gregor Jansen, director of the Kunsthalle Düsseldorf in Germany.

Future Imaginaries, the collective exhibition at The Autry Museum of the American West, explores the rise of Futurism in contemporary Indigenous art as a means of enduring colonial trauma, creating alternative futures and advocating for Indigenous technologies in a more inclusive present and sustainable future.

FUTURE IMAGINARIES: INDIGENOUS ART, FASHION & TECHNOLOGY

Future Imaginaries, the collective exhibition at The Autry Museum of the American West, explores the rise of Futurism in contemporary Indigenous art as a means of enduring colonial trauma, creating alternative futures and advocating for Indigenous technologies in a more inclusive present and sustainable future.

The Mexico Pavilion at the Venice Biennale 2024 proposes an immersive experience that invites the viewer to reflect on the act of migrating and its impact on identity and sense of belonging. As we marched away, we were always coming back is Erick Meyenberg's project curated by Tania Ragasol. It includes elements created in Mexico, Italy and Albania.

THE PATH OF MEMORIES – MEXICO AT THE BIENNALE

The Mexico Pavilion at the Venice Biennale 2024 proposes an immersive experience that invites the viewer to reflect on the act of migrating and its impact on identity and sense of belonging. As we marched away, we were always coming back is Erick Meyenberg's project curated by Tania Ragasol. It includes elements created in Mexico, Italy and Albania.

Disobedience Archive is a video archive project in constant transformation, linking artistic practices and political action. At the Venice Biennale exhibition, it takes the form of The Zoentrope, a pre-cinematographic machine that gives life to a space that generates new perspectives.

A GUIDE FOR PRACTICING DISOBEDIENCE

Disobedience Archive is a video archive project in constant transformation, linking artistic practices and political action. At the Venice Biennale exhibition, it takes the form of The Zoentrope, a pre-cinematographic machine that gives life to a space that generates new perspectives.

Crisis Galería announced the recent acquisition of the painting Cosmovisión Huitoto (2022) by the outstanding indigenous artist Santiago Yahuarcani by the Museum of Modern Art of New York (MoMA). This extraordinary large format work, made with natural dyes and acrylic paint on llanchama, is one of the largest produced by the artist with more than two meters high and four meters wide.

SANTIAGO YAHUARCANI ENTERS THE MoMA COLLECTION

Crisis Galería announced the recent acquisition of the painting Cosmovisión Huitoto (2022) by the outstanding indigenous artist Santiago Yahuarcani by the Museum of Modern Art of New York (MoMA). This extraordinary large format work, made with natural dyes and acrylic paint on llanchama, is one of the largest produced by the artist with more than two meters high and four meters wide.

The 2024 edition of the Venice Biennale is coming to an end. Stranieri Ovunque - Foreigners Everywhere, curated by Brazilian Adriano Pedrosa, offered a reflection through art about migration and borders, recurring themes in today's global discussion. Arte al Día was present to cover the 60th International Exhibition, not only to bring the work of more than 300 artists from almost 100 countries, but also to focus on the contribution of Latin American artists to the global scene, whose presence marked a high point in this edition.

VENICE BIENNALE 2024 – LATIN AMERICA EVERYWHERE

The 2024 edition of the Venice Biennale is coming to an end. Stranieri Ovunque - Foreigners Everywhere, curated by Brazilian Adriano Pedrosa, offered a reflection through art about migration and borders, recurring themes in today's global discussion. Arte al Día was present to cover the 60th International Exhibition, not only to bring the work of more than 300 artists from almost 100 countries, but also to focus on the contribution of Latin American artists to the global scene, whose presence marked a high point in this edition.

The Venice Biennale 2024 offers an exceptional platform for examining the challenges and opportunities facing the future. The pavilions of Japan, Germany, Switzerland and Hungary trace different forms of looking at and thinking about the world to come, projecting visions of the environment, equilibrium, adaptation, world order and, of course, collective memory.

POSSIBLE FUTURES AT THE VENICE BIENNALE

The Venice Biennale 2024 offers an exceptional platform for examining the challenges and opportunities facing the future. The pavilions of Japan, Germany, Switzerland and Hungary trace different forms of looking at and thinking about the world to come, projecting visions of the environment, equilibrium, adaptation, world order and, of course, collective memory.

The voices of Latin American artists emerge strongly in this 2024 edition of the Venice Biennale. Claudia Alarcón, Julia Isídrez and Juana Marta Rodas, Ana Segovia, Frieda Toranzo Jaeger and Claudia Andújar lead viewers on a profound journey through their cultural heritage and unique artistic practices.

FIVE LATIN AMERICAN ARTISTS EXHIBITING FOR THE FIRST TIME AT THE VENICE BIENNALE

The voices of Latin American artists emerge strongly in this 2024 edition of the Venice Biennale. Claudia Alarcón, Julia Isídrez and Juana Marta Rodas, Ana Segovia, Frieda Toranzo Jaeger and Claudia Andújar lead viewers on a profound journey through their cultural heritage and unique artistic practices.

It takes an Island to Feel this Good is Darja Bajagić’s exhibition for the Montenegro pavilion at Venice Biennale 2024. Curated by Ana Simona Zelenović and organized by the Museum of Contemporary Art of Montenegro at the initiative of commissioner Vladislav Šćepanović, the exhibition will present a critical consideration of the culture of collective memory and the relationship to shared historical heritage.

ICONOGRAPHY, MEMORY AND HISTORY - THE MONTENEGRO PAVILION

It takes an Island to Feel this Good is Darja Bajagić’s exhibition for the Montenegro pavilion at Venice Biennale 2024. Curated by Ana Simona Zelenović and organized by the Museum of Contemporary Art of Montenegro at the initiative of commissioner Vladislav Šćepanović, the exhibition will present a critical consideration of the culture of collective memory and the relationship to shared historical heritage.

The monumental commission by British artist John Akomfrah RA for the 2024 Venice Biennale is a multi-layered exhibition which encourages visitors to experience the British Pavilion’s 19th century neoclassical building in a new way.

THE SOUNDS OF TIME – UNITED KINGDOM AT THE VENICE BIENNALE

The monumental commission by British artist John Akomfrah RA for the 2024 Venice Biennale is a multi-layered exhibition which encourages visitors to experience the British Pavilion’s 19th century neoclassical building in a new way.

Engaging with the theme of Adriano Pedrosa’s main exhibition for the Venice Biennale, Stranieri Ovunque—Foreigners Everywhere, Vlatka Horvat’s project for the Croatian Pavilion by the Means at Hand, curated by Antonia Majaca, exists as an accumulative exhibition of artworks by a wide-ranging group of international artists living as “foreigners,” reflecting on questions and urgencies of the diasporic experience.

CROATIAN PAVILION AT THE VENICE BIENNALE

Engaging with the theme of Adriano Pedrosa’s main exhibition for the Venice Biennale, Stranieri Ovunque—Foreigners Everywhere, Vlatka Horvat’s project for the Croatian Pavilion by the Means at Hand, curated by Antonia Majaca, exists as an accumulative exhibition of artworks by a wide-ranging group of international artists living as “foreigners,” reflecting on questions and urgencies of the diasporic experience.

The title of the 60th International Art Exhibition of the Biennale di Venezia, "Stranieri Ovunque", refers, in part, to foreignness as the inherent nature of the subject. Understood in this way, the national pavilions of Spain, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom exhibit artistic proposals that develop the theme of colonialism and reconstruct histories, remedy ties between identity and territory, and explore the dramatic plurality of this potent historical axis. That said, this review does not intend to unveil or unpack the most unjust transcendental truths, but merely to reflect on the musings of others.

THREE PAVILIONS AT BIENNALE 2024 THAT EXPLORE THEIR OWN COLONIAL PASTS

The title of the 60th International Art Exhibition of the Biennale di Venezia, "Stranieri Ovunque", refers, in part, to foreignness as the inherent nature of the subject. Understood in this way, the national pavilions of Spain, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom exhibit artistic proposals that develop the theme of colonialism and reconstruct histories, remedy ties between identity and territory, and explore the dramatic plurality of this potent historical axis. That said, this review does not intend to unveil or unpack the most unjust transcendental truths, but merely to reflect on the musings of others.

The Mongolian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale presents artist Ochirbold Ayurzana with the exhibition Discovering the Present from the Future. The proposal is curated by Oyuntuya Oyunjargal, the Cultural Envoy of Mongolia to Germany, and co-curated by Gregor Jansen, director of the Kunsthalle Düsseldorf in Germany.

OCHIRBOLD AYURZANA AT THE MONGOLIAN PAVILION

The Mongolian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale presents artist Ochirbold Ayurzana with the exhibition Discovering the Present from the Future. The proposal is curated by Oyuntuya Oyunjargal, the Cultural Envoy of Mongolia to Germany, and co-curated by Gregor Jansen, director of the Kunsthalle Düsseldorf in Germany.

Future Imaginaries, the collective exhibition at The Autry Museum of the American West, explores the rise of Futurism in contemporary Indigenous art as a means of enduring colonial trauma, creating alternative futures and advocating for Indigenous technologies in a more inclusive present and sustainable future.

FUTURE IMAGINARIES: INDIGENOUS ART, FASHION & TECHNOLOGY

Future Imaginaries, the collective exhibition at The Autry Museum of the American West, explores the rise of Futurism in contemporary Indigenous art as a means of enduring colonial trauma, creating alternative futures and advocating for Indigenous technologies in a more inclusive present and sustainable future.

The Mexico Pavilion at the Venice Biennale 2024 proposes an immersive experience that invites the viewer to reflect on the act of migrating and its impact on identity and sense of belonging. As we marched away, we were always coming back is Erick Meyenberg's project curated by Tania Ragasol. It includes elements created in Mexico, Italy and Albania.

THE PATH OF MEMORIES – MEXICO AT THE BIENNALE

The Mexico Pavilion at the Venice Biennale 2024 proposes an immersive experience that invites the viewer to reflect on the act of migrating and its impact on identity and sense of belonging. As we marched away, we were always coming back is Erick Meyenberg's project curated by Tania Ragasol. It includes elements created in Mexico, Italy and Albania.

Disobedience Archive is a video archive project in constant transformation, linking artistic practices and political action. At the Venice Biennale exhibition, it takes the form of The Zoentrope, a pre-cinematographic machine that gives life to a space that generates new perspectives.

A GUIDE FOR PRACTICING DISOBEDIENCE

Disobedience Archive is a video archive project in constant transformation, linking artistic practices and political action. At the Venice Biennale exhibition, it takes the form of The Zoentrope, a pre-cinematographic machine that gives life to a space that generates new perspectives.

Crisis Galería announced the recent acquisition of the painting Cosmovisión Huitoto (2022) by the outstanding indigenous artist Santiago Yahuarcani by the Museum of Modern Art of New York (MoMA). This extraordinary large format work, made with natural dyes and acrylic paint on llanchama, is one of the largest produced by the artist with more than two meters high and four meters wide.

SANTIAGO YAHUARCANI ENTERS THE MoMA COLLECTION

Crisis Galería announced the recent acquisition of the painting Cosmovisión Huitoto (2022) by the outstanding indigenous artist Santiago Yahuarcani by the Museum of Modern Art of New York (MoMA). This extraordinary large format work, made with natural dyes and acrylic paint on llanchama, is one of the largest produced by the artist with more than two meters high and four meters wide.

The 2024 edition of the Venice Biennale is coming to an end. Stranieri Ovunque - Foreigners Everywhere, curated by Brazilian Adriano Pedrosa, offered a reflection through art about migration and borders, recurring themes in today's global discussion. Arte al Día was present to cover the 60th International Exhibition, not only to bring the work of more than 300 artists from almost 100 countries, but also to focus on the contribution of Latin American artists to the global scene, whose presence marked a high point in this edition.

VENICE BIENNALE 2024 – LATIN AMERICA EVERYWHERE

The 2024 edition of the Venice Biennale is coming to an end. Stranieri Ovunque - Foreigners Everywhere, curated by Brazilian Adriano Pedrosa, offered a reflection through art about migration and borders, recurring themes in today's global discussion. Arte al Día was present to cover the 60th International Exhibition, not only to bring the work of more than 300 artists from almost 100 countries, but also to focus on the contribution of Latin American artists to the global scene, whose presence marked a high point in this edition.

The Venice Biennale 2024 offers an exceptional platform for examining the challenges and opportunities facing the future. The pavilions of Japan, Germany, Switzerland and Hungary trace different forms of looking at and thinking about the world to come, projecting visions of the environment, equilibrium, adaptation, world order and, of course, collective memory.

POSSIBLE FUTURES AT THE VENICE BIENNALE

The Venice Biennale 2024 offers an exceptional platform for examining the challenges and opportunities facing the future. The pavilions of Japan, Germany, Switzerland and Hungary trace different forms of looking at and thinking about the world to come, projecting visions of the environment, equilibrium, adaptation, world order and, of course, collective memory.

The voices of Latin American artists emerge strongly in this 2024 edition of the Venice Biennale. Claudia Alarcón, Julia Isídrez and Juana Marta Rodas, Ana Segovia, Frieda Toranzo Jaeger and Claudia Andújar lead viewers on a profound journey through their cultural heritage and unique artistic practices.

FIVE LATIN AMERICAN ARTISTS EXHIBITING FOR THE FIRST TIME AT THE VENICE BIENNALE

The voices of Latin American artists emerge strongly in this 2024 edition of the Venice Biennale. Claudia Alarcón, Julia Isídrez and Juana Marta Rodas, Ana Segovia, Frieda Toranzo Jaeger and Claudia Andújar lead viewers on a profound journey through their cultural heritage and unique artistic practices.

It takes an Island to Feel this Good is Darja Bajagić’s exhibition for the Montenegro pavilion at Venice Biennale 2024. Curated by Ana Simona Zelenović and organized by the Museum of Contemporary Art of Montenegro at the initiative of commissioner Vladislav Šćepanović, the exhibition will present a critical consideration of the culture of collective memory and the relationship to shared historical heritage.

ICONOGRAPHY, MEMORY AND HISTORY - THE MONTENEGRO PAVILION

It takes an Island to Feel this Good is Darja Bajagić’s exhibition for the Montenegro pavilion at Venice Biennale 2024. Curated by Ana Simona Zelenović and organized by the Museum of Contemporary Art of Montenegro at the initiative of commissioner Vladislav Šćepanović, the exhibition will present a critical consideration of the culture of collective memory and the relationship to shared historical heritage.

The monumental commission by British artist John Akomfrah RA for the 2024 Venice Biennale is a multi-layered exhibition which encourages visitors to experience the British Pavilion’s 19th century neoclassical building in a new way.

THE SOUNDS OF TIME – UNITED KINGDOM AT THE VENICE BIENNALE

The monumental commission by British artist John Akomfrah RA for the 2024 Venice Biennale is a multi-layered exhibition which encourages visitors to experience the British Pavilion’s 19th century neoclassical building in a new way.

Engaging with the theme of Adriano Pedrosa’s main exhibition for the Venice Biennale, Stranieri Ovunque—Foreigners Everywhere, Vlatka Horvat’s project for the Croatian Pavilion by the Means at Hand, curated by Antonia Majaca, exists as an accumulative exhibition of artworks by a wide-ranging group of international artists living as “foreigners,” reflecting on questions and urgencies of the diasporic experience.

CROATIAN PAVILION AT THE VENICE BIENNALE

Engaging with the theme of Adriano Pedrosa’s main exhibition for the Venice Biennale, Stranieri Ovunque—Foreigners Everywhere, Vlatka Horvat’s project for the Croatian Pavilion by the Means at Hand, curated by Antonia Majaca, exists as an accumulative exhibition of artworks by a wide-ranging group of international artists living as “foreigners,” reflecting on questions and urgencies of the diasporic experience.

The title of the 60th International Art Exhibition of the Biennale di Venezia, "Stranieri Ovunque", refers, in part, to foreignness as the inherent nature of the subject. Understood in this way, the national pavilions of Spain, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom exhibit artistic proposals that develop the theme of colonialism and reconstruct histories, remedy ties between identity and territory, and explore the dramatic plurality of this potent historical axis. That said, this review does not intend to unveil or unpack the most unjust transcendental truths, but merely to reflect on the musings of others.

THREE PAVILIONS AT BIENNALE 2024 THAT EXPLORE THEIR OWN COLONIAL PASTS

The title of the 60th International Art Exhibition of the Biennale di Venezia, "Stranieri Ovunque", refers, in part, to foreignness as the inherent nature of the subject. Understood in this way, the national pavilions of Spain, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom exhibit artistic proposals that develop the theme of colonialism and reconstruct histories, remedy ties between identity and territory, and explore the dramatic plurality of this potent historical axis. That said, this review does not intend to unveil or unpack the most unjust transcendental truths, but merely to reflect on the musings of others.

The Mongolian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale presents artist Ochirbold Ayurzana with the exhibition Discovering the Present from the Future. The proposal is curated by Oyuntuya Oyunjargal, the Cultural Envoy of Mongolia to Germany, and co-curated by Gregor Jansen, director of the Kunsthalle Düsseldorf in Germany.

OCHIRBOLD AYURZANA AT THE MONGOLIAN PAVILION

The Mongolian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale presents artist Ochirbold Ayurzana with the exhibition Discovering the Present from the Future. The proposal is curated by Oyuntuya Oyunjargal, the Cultural Envoy of Mongolia to Germany, and co-curated by Gregor Jansen, director of the Kunsthalle Düsseldorf in Germany.

Future Imaginaries, the collective exhibition at The Autry Museum of the American West, explores the rise of Futurism in contemporary Indigenous art as a means of enduring colonial trauma, creating alternative futures and advocating for Indigenous technologies in a more inclusive present and sustainable future.

FUTURE IMAGINARIES: INDIGENOUS ART, FASHION & TECHNOLOGY

Future Imaginaries, the collective exhibition at The Autry Museum of the American West, explores the rise of Futurism in contemporary Indigenous art as a means of enduring colonial trauma, creating alternative futures and advocating for Indigenous technologies in a more inclusive present and sustainable future.

The Mexico Pavilion at the Venice Biennale 2024 proposes an immersive experience that invites the viewer to reflect on the act of migrating and its impact on identity and sense of belonging. As we marched away, we were always coming back is Erick Meyenberg's project curated by Tania Ragasol. It includes elements created in Mexico, Italy and Albania.

THE PATH OF MEMORIES – MEXICO AT THE BIENNALE

The Mexico Pavilion at the Venice Biennale 2024 proposes an immersive experience that invites the viewer to reflect on the act of migrating and its impact on identity and sense of belonging. As we marched away, we were always coming back is Erick Meyenberg's project curated by Tania Ragasol. It includes elements created in Mexico, Italy and Albania.

Disobedience Archive is a video archive project in constant transformation, linking artistic practices and political action. At the Venice Biennale exhibition, it takes the form of The Zoentrope, a pre-cinematographic machine that gives life to a space that generates new perspectives.

A GUIDE FOR PRACTICING DISOBEDIENCE

Disobedience Archive is a video archive project in constant transformation, linking artistic practices and political action. At the Venice Biennale exhibition, it takes the form of The Zoentrope, a pre-cinematographic machine that gives life to a space that generates new perspectives.

Crisis Galería announced the recent acquisition of the painting Cosmovisión Huitoto (2022) by the outstanding indigenous artist Santiago Yahuarcani by the Museum of Modern Art of New York (MoMA). This extraordinary large format work, made with natural dyes and acrylic paint on llanchama, is one of the largest produced by the artist with more than two meters high and four meters wide.

SANTIAGO YAHUARCANI ENTERS THE MoMA COLLECTION

Crisis Galería announced the recent acquisition of the painting Cosmovisión Huitoto (2022) by the outstanding indigenous artist Santiago Yahuarcani by the Museum of Modern Art of New York (MoMA). This extraordinary large format work, made with natural dyes and acrylic paint on llanchama, is one of the largest produced by the artist with more than two meters high and four meters wide.

The 2024 edition of the Venice Biennale is coming to an end. Stranieri Ovunque - Foreigners Everywhere, curated by Brazilian Adriano Pedrosa, offered a reflection through art about migration and borders, recurring themes in today's global discussion. Arte al Día was present to cover the 60th International Exhibition, not only to bring the work of more than 300 artists from almost 100 countries, but also to focus on the contribution of Latin American artists to the global scene, whose presence marked a high point in this edition.

VENICE BIENNALE 2024 – LATIN AMERICA EVERYWHERE

The 2024 edition of the Venice Biennale is coming to an end. Stranieri Ovunque - Foreigners Everywhere, curated by Brazilian Adriano Pedrosa, offered a reflection through art about migration and borders, recurring themes in today's global discussion. Arte al Día was present to cover the 60th International Exhibition, not only to bring the work of more than 300 artists from almost 100 countries, but also to focus on the contribution of Latin American artists to the global scene, whose presence marked a high point in this edition.

The Venice Biennale 2024 offers an exceptional platform for examining the challenges and opportunities facing the future. The pavilions of Japan, Germany, Switzerland and Hungary trace different forms of looking at and thinking about the world to come, projecting visions of the environment, equilibrium, adaptation, world order and, of course, collective memory.

POSSIBLE FUTURES AT THE VENICE BIENNALE

The Venice Biennale 2024 offers an exceptional platform for examining the challenges and opportunities facing the future. The pavilions of Japan, Germany, Switzerland and Hungary trace different forms of looking at and thinking about the world to come, projecting visions of the environment, equilibrium, adaptation, world order and, of course, collective memory.

The voices of Latin American artists emerge strongly in this 2024 edition of the Venice Biennale. Claudia Alarcón, Julia Isídrez and Juana Marta Rodas, Ana Segovia, Frieda Toranzo Jaeger and Claudia Andújar lead viewers on a profound journey through their cultural heritage and unique artistic practices.

FIVE LATIN AMERICAN ARTISTS EXHIBITING FOR THE FIRST TIME AT THE VENICE BIENNALE

The voices of Latin American artists emerge strongly in this 2024 edition of the Venice Biennale. Claudia Alarcón, Julia Isídrez and Juana Marta Rodas, Ana Segovia, Frieda Toranzo Jaeger and Claudia Andújar lead viewers on a profound journey through their cultural heritage and unique artistic practices.

It takes an Island to Feel this Good is Darja Bajagić’s exhibition for the Montenegro pavilion at Venice Biennale 2024. Curated by Ana Simona Zelenović and organized by the Museum of Contemporary Art of Montenegro at the initiative of commissioner Vladislav Šćepanović, the exhibition will present a critical consideration of the culture of collective memory and the relationship to shared historical heritage.

ICONOGRAPHY, MEMORY AND HISTORY - THE MONTENEGRO PAVILION

It takes an Island to Feel this Good is Darja Bajagić’s exhibition for the Montenegro pavilion at Venice Biennale 2024. Curated by Ana Simona Zelenović and organized by the Museum of Contemporary Art of Montenegro at the initiative of commissioner Vladislav Šćepanović, the exhibition will present a critical consideration of the culture of collective memory and the relationship to shared historical heritage.

The monumental commission by British artist John Akomfrah RA for the 2024 Venice Biennale is a multi-layered exhibition which encourages visitors to experience the British Pavilion’s 19th century neoclassical building in a new way.

THE SOUNDS OF TIME – UNITED KINGDOM AT THE VENICE BIENNALE

The monumental commission by British artist John Akomfrah RA for the 2024 Venice Biennale is a multi-layered exhibition which encourages visitors to experience the British Pavilion’s 19th century neoclassical building in a new way.

Engaging with the theme of Adriano Pedrosa’s main exhibition for the Venice Biennale, Stranieri Ovunque—Foreigners Everywhere, Vlatka Horvat’s project for the Croatian Pavilion by the Means at Hand, curated by Antonia Majaca, exists as an accumulative exhibition of artworks by a wide-ranging group of international artists living as “foreigners,” reflecting on questions and urgencies of the diasporic experience.

CROATIAN PAVILION AT THE VENICE BIENNALE

Engaging with the theme of Adriano Pedrosa’s main exhibition for the Venice Biennale, Stranieri Ovunque—Foreigners Everywhere, Vlatka Horvat’s project for the Croatian Pavilion by the Means at Hand, curated by Antonia Majaca, exists as an accumulative exhibition of artworks by a wide-ranging group of international artists living as “foreigners,” reflecting on questions and urgencies of the diasporic experience.

The title of the 60th International Art Exhibition of the Biennale di Venezia, "Stranieri Ovunque", refers, in part, to foreignness as the inherent nature of the subject. Understood in this way, the national pavilions of Spain, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom exhibit artistic proposals that develop the theme of colonialism and reconstruct histories, remedy ties between identity and territory, and explore the dramatic plurality of this potent historical axis. That said, this review does not intend to unveil or unpack the most unjust transcendental truths, but merely to reflect on the musings of others.

THREE PAVILIONS AT BIENNALE 2024 THAT EXPLORE THEIR OWN COLONIAL PASTS

The title of the 60th International Art Exhibition of the Biennale di Venezia, "Stranieri Ovunque", refers, in part, to foreignness as the inherent nature of the subject. Understood in this way, the national pavilions of Spain, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom exhibit artistic proposals that develop the theme of colonialism and reconstruct histories, remedy ties between identity and territory, and explore the dramatic plurality of this potent historical axis. That said, this review does not intend to unveil or unpack the most unjust transcendental truths, but merely to reflect on the musings of others.

The Mongolian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale presents artist Ochirbold Ayurzana with the exhibition Discovering the Present from the Future. The proposal is curated by Oyuntuya Oyunjargal, the Cultural Envoy of Mongolia to Germany, and co-curated by Gregor Jansen, director of the Kunsthalle Düsseldorf in Germany.

OCHIRBOLD AYURZANA AT THE MONGOLIAN PAVILION

The Mongolian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale presents artist Ochirbold Ayurzana with the exhibition Discovering the Present from the Future. The proposal is curated by Oyuntuya Oyunjargal, the Cultural Envoy of Mongolia to Germany, and co-curated by Gregor Jansen, director of the Kunsthalle Düsseldorf in Germany.

Future Imaginaries, the collective exhibition at The Autry Museum of the American West, explores the rise of Futurism in contemporary Indigenous art as a means of enduring colonial trauma, creating alternative futures and advocating for Indigenous technologies in a more inclusive present and sustainable future.

FUTURE IMAGINARIES: INDIGENOUS ART, FASHION & TECHNOLOGY

Future Imaginaries, the collective exhibition at The Autry Museum of the American West, explores the rise of Futurism in contemporary Indigenous art as a means of enduring colonial trauma, creating alternative futures and advocating for Indigenous technologies in a more inclusive present and sustainable future.

The Mexico Pavilion at the Venice Biennale 2024 proposes an immersive experience that invites the viewer to reflect on the act of migrating and its impact on identity and sense of belonging. As we marched away, we were always coming back is Erick Meyenberg's project curated by Tania Ragasol. It includes elements created in Mexico, Italy and Albania.

THE PATH OF MEMORIES – MEXICO AT THE BIENNALE

The Mexico Pavilion at the Venice Biennale 2024 proposes an immersive experience that invites the viewer to reflect on the act of migrating and its impact on identity and sense of belonging. As we marched away, we were always coming back is Erick Meyenberg's project curated by Tania Ragasol. It includes elements created in Mexico, Italy and Albania.

Disobedience Archive is a video archive project in constant transformation, linking artistic practices and political action. At the Venice Biennale exhibition, it takes the form of The Zoentrope, a pre-cinematographic machine that gives life to a space that generates new perspectives.

A GUIDE FOR PRACTICING DISOBEDIENCE

Disobedience Archive is a video archive project in constant transformation, linking artistic practices and political action. At the Venice Biennale exhibition, it takes the form of The Zoentrope, a pre-cinematographic machine that gives life to a space that generates new perspectives.

Crisis Galería announced the recent acquisition of the painting Cosmovisión Huitoto (2022) by the outstanding indigenous artist Santiago Yahuarcani by the Museum of Modern Art of New York (MoMA). This extraordinary large format work, made with natural dyes and acrylic paint on llanchama, is one of the largest produced by the artist with more than two meters high and four meters wide.

SANTIAGO YAHUARCANI ENTERS THE MoMA COLLECTION

Crisis Galería announced the recent acquisition of the painting Cosmovisión Huitoto (2022) by the outstanding indigenous artist Santiago Yahuarcani by the Museum of Modern Art of New York (MoMA). This extraordinary large format work, made with natural dyes and acrylic paint on llanchama, is one of the largest produced by the artist with more than two meters high and four meters wide.

The 2024 edition of the Venice Biennale is coming to an end. Stranieri Ovunque - Foreigners Everywhere, curated by Brazilian Adriano Pedrosa, offered a reflection through art about migration and borders, recurring themes in today's global discussion. Arte al Día was present to cover the 60th International Exhibition, not only to bring the work of more than 300 artists from almost 100 countries, but also to focus on the contribution of Latin American artists to the global scene, whose presence marked a high point in this edition.

VENICE BIENNALE 2024 – LATIN AMERICA EVERYWHERE

The 2024 edition of the Venice Biennale is coming to an end. Stranieri Ovunque - Foreigners Everywhere, curated by Brazilian Adriano Pedrosa, offered a reflection through art about migration and borders, recurring themes in today's global discussion. Arte al Día was present to cover the 60th International Exhibition, not only to bring the work of more than 300 artists from almost 100 countries, but also to focus on the contribution of Latin American artists to the global scene, whose presence marked a high point in this edition.

The Venice Biennale 2024 offers an exceptional platform for examining the challenges and opportunities facing the future. The pavilions of Japan, Germany, Switzerland and Hungary trace different forms of looking at and thinking about the world to come, projecting visions of the environment, equilibrium, adaptation, world order and, of course, collective memory.

POSSIBLE FUTURES AT THE VENICE BIENNALE

The Venice Biennale 2024 offers an exceptional platform for examining the challenges and opportunities facing the future. The pavilions of Japan, Germany, Switzerland and Hungary trace different forms of looking at and thinking about the world to come, projecting visions of the environment, equilibrium, adaptation, world order and, of course, collective memory.