Susy Iglicki

Curator’s Voice Art Projects, Miami

Photography-based works by Susy Iglicki tie together very diverse space-historical times, showing how the river of blood that crosses the history of the world tends to bury the signs of identity. Her art tries to make us see, to re-humanize.

On a first impression, one can miss the line of continuity between the photographs of the city of Caracas that are added to the tradition of photography of the architecture of Latin American large cities that reflects the splitting of the social structures, and the pieces of photographic support installed in the light boxes that refer us to the personal or collective memory of the Jewish people, in which the artist goes back to her personal identity. And yet the vision that seeks to recognize the face of her ancestral past, without which it cannot be explained, but also the face of the social world that constitutes a shared present which is unfortunately invisible for a huge social sector, is one and the same.

Her art is a way of tying herself to her own identity through the portrait of the existences that preceded her own, or through the memory of the indescribable that will never be completely left behind, but also of recognizing herself in that river which is the others who are unable to see themselves and who converge in the present of Latin American large cities.

In Ich Bin (I am), Iglicki continues those earlier works in which she developed the theme of identity with the silhouettes of her ancestors over the image of the sea, which for her is a “metaphor for spiritual connections”. The irrational current of violence that severs lives − whose sea route transit she visualizes in a piece recalling the trip from Europe to America made by her ancestors when they came to settle in Venezuela − can be embodied in spaces and times so distant as the east and the west. The revelation of the continuity of the river of violence contained in Iglicki’s images preserves us from oblivion of the past and from the blindness of the present, connecting identity to a form of compassion that vindicates the human.

One of the most moving pieces, terrible in its beauty, Wir Waren (We were), is constructed with the photographs of shoes that used to pile up in concentration camps before the final moments of those who succumbed in the extermination of the holocaust. In the same way, in the diptych Morgue she uses a photograph of that place in Caracas, taken by a journalist from the newspaper El Nacional that provoked a scandal. “Ironically – says Iglicki – in our cities the images of the dead are allowed in the streets, but not in publications”.

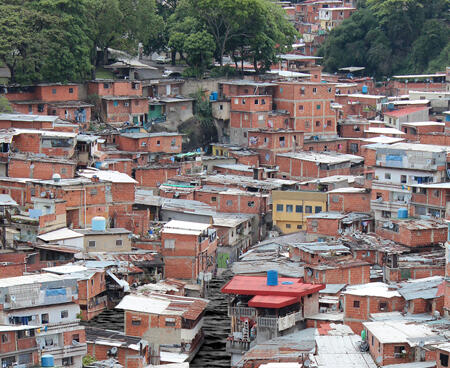

In the first part of the diptych she takes up images of tragic events published by the press during three months, while in Requiem, Iglicki connects that extreme violence to the vision of the marginal zones where young people die with horrifying frequency. The black river that she intervenes digitally to make it resemble a flow of oil that splits the crawling construction of precarious houses of the slums of Caracas in two refers us to that economic violence that also erases the signs of identity of large fragments of humanity, while chasing luxury mirages.

By intervening the photograph of the concentration of shacks in a quarter of one of the poverty belts of Caracas so as to leave only one of them in color, she restores the identity that is mined by the extended socio-economic violence that de-humanizes those who exercise it or suffer it.

-

Black River, 2011. Digital Print/Impresión digital

Black River, 2011. Digital Print/Impresión digital

Courtesy of the artist /Cortesía de la artista.