NO WALLS, BUT TRANSPARENCIES

"The ruins in their singularity are the most living thing in history, since only what has survived its destruction, what has remained in ruins, lives historically," says María Zambrano. Jorge Scrimaglio, Argentine architect, is a builder who appeals to that spirit that Kahn defined in the same sense: “you have to surround buildings with ruins”. And a building that appeals to be a ruin, with walls that are not such, that house emptiness and serve as support to a sense that extends triumphant; as a way of survival, not from what it was, but from what it did not become. Empty as absence. Making concrete a possibility not yet realized, like the life of the ruins that are indefinite and more than any other spectacle awakens in the mind of those who contemplate them the impression of an infinity.

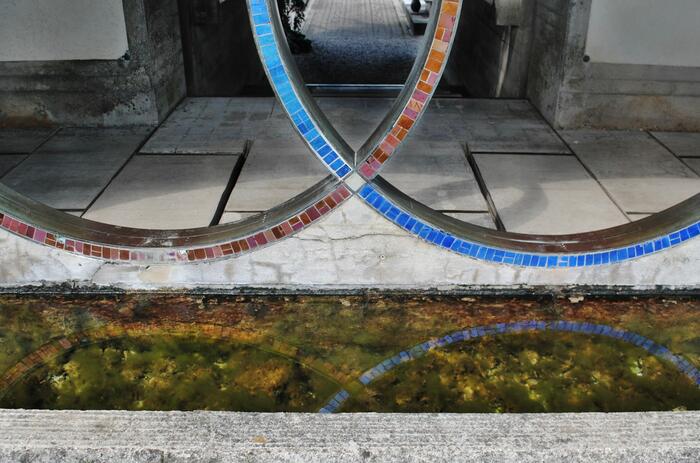

Scrimaglio appeals to the world of American geometricism of the Mezo-American temples, which come to us as ruins, and builds walls of screened bricks that house emptiness with a material logic that more than walls consists of transparencies. "It", brick, IS a non-subjective element, which does not have intrinsic properties, but rather a situation: "It" can be floor, ceiling, staircase, window, eventually a wall, according to the place it occupies in space ... "It" —the insistent brick— builds, breaks, covers, borders, rises, falls, supports, retains, becomes absent, disappears, without altering the unit.

Between the mid-1960s and the 1980s, he built notable works, such as the Alorda house (1968/73), which I visited after one of the trips we made with AVB workshop students in 2014 to the city of Rosario.

Located in a territory of meager measures, the proposal is overwhelming. The entire program was decided to be located at the back, leaving a generous patio in front. And it is this patio and its rigorous sieved brick wall that houses the void, the first thing that strikes the visitor. Following an impeccable constructive and geometric logic, it is accessed after crossing the only way in that the house has from the front. A thick wooden slatted gate decorated with a rhomboid iconography - the pampas guard motif - is repeated on the brick wall, and from there we enter the garage/hall that leads to the rather meager kitchen.

We were greeted, after a failed first attempt, by the actor's niece, Yanina Alorda, who had known the house since her childhood. It was then that we were able to visit with the whole group, not only the magnificent interior patio with its brick stairs and particularly high elevations (since they respond to the mono-material module with which it is built), but also the exterior light devices that repeat the staggered brick motif or bedroom ceilings seen in the photo set.

It is clear that it is a very particular work, out of any canon ... the Alorda house is the first significant work by Scrimaglio that wisely assumes those words that Gerardo Caballero - last Argentine curator of the Venice Architecture Biennale (2020-21) - dedicates:

"It's like taking a brick and not making a wall ...

There are no walls but there are transparencies,

There are no windows but there is light,

There is no scale but there are relationships,

The result is the magnificent manipulation of the same element. The desire to create a vacuum determines the constructive technique.

A true exercise of architecture."

Jorge Enrique Scrimaglio, architect, was born in Rosario, Santa Fe, Argentina in 1937. He completed his first studies at a public school and at the General José de San Martín National Industrial School, where he specialized as a chemical technician. It was there that he received the first practical experiences in carpentry, blacksmith and foundry workshops. He entered the School of Architecture of the UNL (Universidad Nacional del Litoral) in 1956. At that time, the School depended on the Faculty of Applied Mathematical, Physical and Natural Sciences, directed by the engineer José León Garibay - who a few years later entrusted Scrimaglio with his own house in Fisherton, Rosario (1962-1971) -. During Scrimaglio’s student years, the School of Architecture was directed by the architect Jorge Ferrari Hardoy, a disciple of Le Corbusier and partner with Kurchan and Bonet. Authors of notable modern works from the River Plate area, as well as the internationally famous BKF armchair (Bonet-Kurchan-Ferrari) - an icon of modern Argentine furniture design.

In 1957, Scrimaglio designed his first architectural work: the weekend family home in the Granadero Baigorria nature reserve, on the banks of the Paraná, where he would later install his studio. At that time he is 20 years old and in the 2nd year of college. At the end of that year, he attended the summer course that is dictated at the University of Tucumán by his encouraging teacher, the architect Eduardo Sacriste (1905-1999). Sacriste is a relevant personality of Argentine architecture, Master of great Masters, who a few years later says of his disciple: “Scrimaglio is a true creator, all works, whatever their magnitude, will have interest, they will be a contribution to the architecture medium."

During the last years of his studies, Jorge Scrimaglio produced two works that were to have a marked impact on his later creations: La Librería del Ateneo Universitario, on the ground floor of the Faculty of Mathematical Sciences, and the magnificent little Chapel of the Holy Spirit in the Women's University Home, unfortunately demolished. Both are projected and built in common with his students and function as a kind of “declaration of principles”. The small chapel is recognized in Europe, defined by the eminent Belgian Dominican specialist Fréderic Debuyst as "eloquent expression of the mystical spirit of the Latin American peoples."

In 1961 he graduated as an architect with brilliant qualifications and in 1969 he was called by the Italian architect Enrico Tedeschi, founder of the Mendoza Faculty of Architecture, to teach architecture courses at said faculty.

Scrimaglio developed 25 works during a little over half a century, most of them located in Arroyo Seco, Rosario, General Lagos, Granadero Baigorria and Firmat. His architectural work was also accompanied by the design of furniture, graphic design and successive writings, such as Una arquitectura argentina (An Argentine Architecture) (1983), which summarizes his ideas about what he understands Architecture to be.