MARIA WILLIS AND DENILSON BANIWA ON AMAZOFUTURISM

Maria Willis (Bogota, Colombia 1979) and Denilson Baniwa (Barcelos, Brazil, 1984) are the responsible for Wametisé: ideas for an amazofuturism, one of the special programs curated for ARCO 2025 and that navigates the Amazon and its growing impact on contemporary art. This proposal proposes a scenario of representation and dialogue through a selection of galleries and guest artists who will raise, through their works and their realities, the different conceptions of the Amazonian world and the possibilities of a collective future.

The program will also materialize this space in the form of a forum, an agenda of interventions and conversations that invites reflection on the difficult balance between the ancestral and the technological in the construction of this future and how to face the challenges and possibilities of the area. Turned into a place for reflection, it becomes the center of an extensive program that is not exempt of theoretical and critical difficulties that its two curators reveal to us.

How and why Wametisé: ideas for an amazofuturism and what are the objectives of this curatorial activity?

Maria Willis [M.W.]: The idea was to leave aside states and limits. ARCO has been betting on themes for some time now and abandoning the concept of guest countries. In that sense, I proposed to Maribel López to work on the Amazon, because it allowed us to discuss how to understand a region and also how to understand a cause beyond borders. I always wanted to work with Denilson, I called him, and we put forward a proposal that would question those visions that exist, sometimes too stereotyped, about the Amazon.

Denilson Baniwa [D.B.]: The Amazon is a very large area, and I think there has not been enough communication between artists and that is why it was important to build a space where they could meet, make them talk and create an exercise to bring them together. In that sense, Wametisé is conceived with the sense of tracing dynamics that could facilitate that encounter.

-

María Willis y Denilson Baniwa

You mention the issue of the borders of the countries and the natural region, but there are some lines of thesis that advocate for an Amazonia that, although it is a natural region, inescapably drinks from the history of each country, with different degrees of exposure. Knowing that your work is based on treating it as a natural region, don't you think that borders affect this conception that there is not only one Amazon?

D.B.: We are of the opinion that there are many more points in common than those that separate it. The Amazon has the same history, the same themes and, I dare say, similar cultural traits, although, obviously, each community has its own traits. Many have the same mythologies about magical snakes and the rituals and representations are similar. This is very important for us, because we believe more in all those elements of union.

M.W.: The poetics of the myths of origin that exist in the Amazon is a way that allows, from the ancestral, to narrate new possibilities for the future. This is how we propose this futuristic approach. From there, many artists contemplate possible speculations to talk about the human and the natural and the artificial, and from there, amazofuturism is proposed as something close to science fiction. The narratives about the Amazon from art undoubtedly reflect crises, but they are quite renovating and open critiques to stereotypes and allow opening the possibility of redefining science and history. Hence the importance of the decolonial. We do not want to generalize. Of course, there are very specific contexts, and I think the diversity of our project is that each artist is a unique life story and is telling something very particular. Rather than saying that each country has it, I would say that each artist has a specific context. Amazofuturismos talks about diversity and also about overcoming prejudices about the primitive, the isolated, the wild. But, most importantly, it raises awareness about the need for self-determination of the Amazonian peoples and the agency of the jungle itself.

-

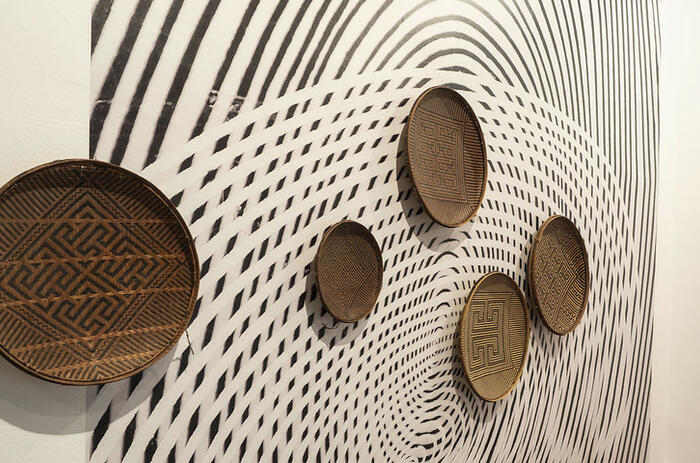

Wametisé: ideas para un amazofuturismo para ARCOmadrid 2025 (IFEMA)

How can a safe environment be established to create these dialogues and make problems and theories visible in the future without the risk that a market such as art, with a very different structural cut, ends up perverting Amazonian art and its peculiarity and idiosyncrasy in all its aspects?

D.B.: That is a question that always arises. There is a radical change in the Amazonian world and in the world of the arts thought by indigenous people in which the occupation of spaces is much discussed. There are many artists who are interested in being in the art market and others in occupying that space to bring benefits to their communities. It is difficult to talk about “artistic perversion” when there are very different thoughts and practices of indigenous artists, but there is an interest in being in art fairs and galleries that were occupied by non-indigenous people who sold works dealing with indigenous themes. Of course, there are many dangers in that self-representation within a space that is super-mercadologic, that is super-capitalist, but there are also artists who have realized the cultural symbolic value of these spaces and the value of their work. Fortunately, the indigenous artists of the Amazon are discussing this insertion into the art market and talking about how to minimize these risks. We cannot answer this question now; we can only observe what will happen in the coming years.

M.W.: I think it is important to address the issue of circulation spaces, from museums and galleries to fairs. It is essential that they be accessible to all the populations that wish to be part of them. Are museums colonized, is there an appropriation of the indigenous from the art circuit? I don't think we should take it for granted. Of course, good practices and ethics must be tracked down. Here and in several projects currently underway in Spain, we are encouraging dialogue and also exchange formats and reviewing categories, such as “art” and “craftsmanship”. Artisans are immense masters and historically they have received less retribution. Why? There are many whys. In amazofuturismos all the indigenous artists, obviously, and the mestizos or white guests have created and existed from within the jungle and in respectful dialogue. All these exhibitions and attention to the Amazon help to make critical analyses. Capitalism is a model to be questioned, and I believe that the proposals of many artists are questioning the way in which current economic models affect their environment in a critical way. What Denilson said about self-representation is key here. In that sense, within the forum, we proposed conversations with Suely Rolnik and Rember Yahuarcani, who is becoming a leader in art on these issues. Also, the program with the Amazon galleries allows opportunities for galleries in the territories. As an outside curator, white, mestizo, I believe in the possibility of permeating or contaminating ourselves, in a good way. I have been going to the Amazon to learn and not to take on anyone's voice, but to generate collaborative ties and hopefully allow for a healing in the way Western ways of thinking have been imposed. I believe in the need to find ways to talk about the difficult issues that exist within the Amazon and also to be agents of change.

That point seems relevant to me, because, obviously, there are subtle and, dare I say, political differences in the conception of vindication, inspiration or appropriation. How to separate them and make viable, in terms of curatorial work, this set of apparently watertight compartments?

D.B.: All relationships are very complex, be they indigenous or non-indigenous, but our exercise as curators of this space is to bring a communitarian perspective to the work. The artists we bring to Madrid are part of this exercise, and we understand that many non-indigenous artists who are and who have a very close relationship with the indigenous populations are at the service of that community. And, at the same time, indigenous artists who live very close to the cities and to Western thought. And that will be very clear in the sequence of conversations and talks during ARCO, where we will see that many artists are appropriating a Western language so that their voice can be heard. We are very careful in the choice of artists to show that Amazonian art today can no longer live in a complete separation, neither from the indigenous world nor from the Western world, due to many influencing factors, and it is necessary for people to understand that the relationship is much closer and that we are dependent on each other.

M.W.: The fairs are short, and that's why they don't allow us to go deeper, but ARCO has been fostering structural changes by opening up to thematic curatorships. It is also key to question the roles of the curator, the collector, the anthropologist and, of course, the artist. Working with Denilson was very fertile and his experience as an artist feeds all these discussions. We are going to allow ourselves to generate this questioning from the forum, where each artist and speaker brings a very valuable story. In our experience as curators, we have been very careful to understand from what place of enunciation comes what is being created and what makes it legitimate. Not only can what the native peoples enunciate be legitimate, there are also very serious voices that are generating crossings and possibilities of cultural translation when it is possible. But there are also times when it is not possible. We have very different belief systems and we should also throw ourselves into the mysteries that the Amazon itself gives us, such as, for example, believing in dreams, letting animals talk to us, understanding that trees walk, and not trying to establish how the world should be from our point of view. To erase beliefs or absolute truths. This curatorship wants to question these commonplaces. We put gender issues on the table, something that is not talked about much in the Amazon, and we allow ourselves an Amazonian futurism that addresses essential aspects from radically new places, allowing art to talk about their problems, which are often not what Western thought believes them to be. We are also interested in intersectionality, being indigenous, trans, among other social factors. The jungle is queer because in it there is such a radical abundance that allows us to understand what we really are: interspecies. We co-depend and coexist, something that the ancestral cosmogonies understood.

A constant has appeared that speaks of a single region, but we are always opposing two elements: a western one, which can come into contact with the indigenous, and an indigenous one, which can come into contact with the western. Thinking at what point a social policy can take precedence over a question of identity or ethnicity, I do not know if there is a certain risk of a norm prevailing over an eminently political norm and vice versa. I think it's something really complicated to address in a curatorial scene.

M.W.: There is an important issue that is even addressed by one of our artists, Brus Rubio, who talks about the fact that the word “anthropology” did not exist in the indigenous field. Anthropologists came to impose certain methods and your question seems fundamental to me, but I think there is no clear answer. To a certain extent, it is impossible not to speak of a mutual contamination. The Institute for Postnatural Studies, who also collaborate in the program, have a very interesting perspective on how to approach, and I think they have done it with extreme care, through the Amazonian architecture to dialogue. There are subtle gestures that denote that we do not want the forum to be a space where this Western idea of lecturers, seminarians on a podium, and people below is perpetuated, but rather the circle. If a person wants to come and criticize, he will say that there is appropriation. And there will be a certain contamination, or a certain inspiration, if we want to see it in a more naive sense, but I think it is worth trying this experiment. What Denilson says is absolutely true: art allows us to be very experimental, and we will have an indication that something is going to happen and will change. If you hold on to that thought, and you are right, there is the West, there is Amazonia, but there are more and more white artists who have lived more in the jungle than in the city and in doing so the same communities have welcomed them as if they were their own. This contamination works as long as it is not understood as a harsh imposition, but as something that allows it to permeate. Now there are a number of more sensitive places where Western art, hard, historical, theoretical, had never been allowed, and now it is entering. The idea of being permeated, of “contaminating” ourselves, is very nice.

D.B.: The world has changed a lot in recent years and there is hardly any Amazonian indigenous community that has not been contacted by the Western world and has not been influenced by the Western world. It is very special, very sensitive, that we can perceive through all the senses a work of art and, at the same time, have people who are interested in participating in this Amazonian change. They are welcome, but not as explorers or as someone who wants to plunder that space, but as someone who wants to participate in that space. I believe that art is a good response, as Maria said, to the world, to all worlds, indigenous, non-indigenous or western.

The Wametisé: ideas for an amazofuturism gallery program will take place during ARCO Madrid 2025. The Wametisé Forum activities will be held from March 6 to 8 at the #amazofuturismo Auditorium, IFEMA Pavilion 7, Partenón, 5, Madrid (Spain).