"NEGOTIATING TO CARRY THE LOAD": A CONVERSATION WITH FABIOLA R. DELGADO

It is difficult to define the exact date on which migration - a natural and profoundly human process - became, in Venezuela, an exodic phenomenon of alarming daily figures, with statistics that exceed all historical precedents and whose future projection only aspires to continue rising. However, it is since 2016 when its popularization and remarkable growth begins to draw a series of images and stories that, from an 'exposed' anonymity (from word of mouth, social networks, personal testimonies), provide an existential proof of what it means to cross a border in the midst of uncertainty, to abandon belongings and values, to forcibly break affective ties and abandon, in many ways, the idea of building a life in the territory that had been inhabited until that moment.

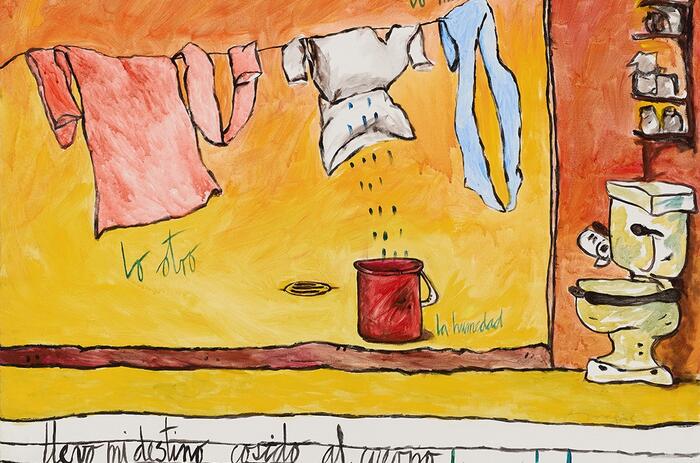

In a conjunction of individual efforts to sublimate the disagreements of the migratory experience, to resignify the poetics of loss, but also to leave an incisive record of what has been lived, the group exhibition Build what we hate. Destroy what we love, curated by Fabiola R. Delgado, develops a series of approaches in which, from their particular places of enunciation, Venezuelan artists Ronald Pizzoferrato, Cassandra Mayela and Juan Diego Perez La Cruz delve into the circumstance of being a migrant in today's globalized world, through artistic practices in which the anonymous voices of displacement find a space of echo and expansion for the construction of a collective testimony.

The exhibition, an apexart (New York) Open Call winner, aims to provide an approach to a complex reality unknown to many, through the sensitive and critical gaze of three diasporic artists who, being part of the millions of Venezuelan migrants, outline a different trajectory of the visual arts in the country: A 'dislocated' Venezuelan art, which still does not cease to reflect on heartfelt and shared problems, "connected in the distance" with a territory in conflict that has made the exception, the normality.

In this conversation with Fabiola R. Delgado, curator of the exhibition, we propose to know a little more about what is built and destroyed in the process of migrating, about the looks towards Venezuela from abroad and about the importance of making visible the continuity of the humanitarian crisis from a reflective, poetic and acute perspective of what happens after crossing the borders.

Manuel Vásquez Ortega: The subject of Venezuelan migration in the 21st century has been present in several of your curatorial projects and research. Where does your interest in this subject come from? Why do you think it is relevant to give it visibility at this time?

Fabiola R. Delgado: My interest in the subject comes from the desire to understand the complexity of this historical phenomenon and to articulate its importance in the international social and political sphere. Migration not only impacts the individual who experiences it firsthand, but also shapes and redefines entire communities-including those who move, those who welcome, and those who are left behind.

Particularly, these projects are also part of an autoethnographic investigation; as a Venezuelan migrant I find myself directly connected to the experiences and challenges faced by my co-nationals as they are forced to leave the country. I also meditate on the rupture that this implies in our family, friendships, professional, cultural circles… There are so many simultaneous pains, a web of losses, and layers of identity that are affected when a new diaspora is born; which motivates me to dig into my own roots and understand -from a distance and without the immediate influence of the national environment- the different contemporary realities of our people. And it is not only a personal quest, it is also a way to explore ideas about the preservation and reconstruction of the fragile memory of a "spilled" country, as well as the construction of new identities that emerge from the fusion of cultures and geographies in movement.

The importance of giving visibility to this theme lies in its ability to promote empathy, understanding and meaningful dialogues around the experiences of those affected by this process (dialogues that go beyond obsolete political divisions and regionalisms).

By highlighting these stories, universal in their individuality, I seek to raise awareness about the realities of migration, and thus encourage a deeper reflection on the social and human aspects involved. At the same time, we cannot ignore the magnitude of the tangible losses and emotional scars that migration leaves in our communities, so with these projects I aspire to create spaces of mourning, of consolation, but also of commemoration that help us process our national traumas and contribute to the healing of the migratory wound.

MVO: How does this interest tie in with Build what we hate. Can you tell us about the title of the exhibition?

FRD: The title of the show, "Build what we hate. Destroy what we love" encapsulates a paradoxical dynamic that reflects the complexity of human interactions with oppressive systems. This duality is not limited to a simple dichotomy, but encompasses a range of daily actions, in which corrupt and violent practices generated in power permeate society and are adopted to survive, and even thrive.

These practices of violence are intertwined with the need to question and change systems that harm us, but at the same time sustain (or suspend) us while "working things out". This tension and reciprocity presents us with a logical challenge, and with that title, I seek to evoke the desire to disarm that which has caused us harm, but with which we have learned to live, whether out of habit, convenience, fear, or weariness.

This dilemma establishes a direct connection with the experiences of Venezuelan migrants, who, despite facing oppressive systems, are forced to negotiate with them in order to cope with the burden. Similarly, the concepts of destruction and construction are strongly linked to migratory processes. Destruction manifests itself in the rupture of familiarity, in the parting of homes, and in the inevitable separation from the homeland. This process of atomization and detachment implies leaving behind physical and emotional places, rooted memories, the identity that has been built in the original context (one destroys what one loves). And as migrants immerse themselves in the journey, the need arises to build new foundations, both physical and symbolic. The construction manifests itself in the creation of new connections, the adaptation to unfamiliar surroundings, and the uncomfortable formation of hybrid identities that merge our roots with the experiences of the new context. Erecting a new reality, especially in a place like the United States (one builds what one hates).

MVO: There is a particular and genuine criterion in the selection of the artists participating in the show, Venezuelan migrant artists who address the theme of exile in their work, as something beyond a place of enunciation but as a condition of their existence. Could you tell us a little about the selection of these three creators?

FRD: The choice of these artists is based on the commitment to highlight authentic and significant voices that address the issues of exile and Venezuelan migration from diverse and honest perspectives. Each artist brings a unique perspective, offering a thoughtful and emotive exploration of the complexities associated with migration experiences, without falling into stereotypes or generalizations, as their own experiences inform their work. For example, in the case of Ronald Pizzoferrato (1988, Caracas, Venezuela), the artist adopts an investigative and documentary approach that not only addresses conflicts, but also highlights the mark left by the migrant, becoming an integral part of the environment and contributing to define it. Cassandra Mayela (1989, Caracas, Venezuela) stands out for her exploration of identities and belonging through textile works, demonstrating her ability to weave deeply personal stories with seemingly ordinary materials. And finally, Juan Diego Pérez la Cruz (1986, Maracaibo, Venezuela) embarks on the rescue of family and national memories, seeking to replicate them in other lands with the resources available to the newcomer.

The three artists also share a concern for safeguarding the identity of migrant individuals, who are not mere subjects in their works, but, in many cases, essential collaborators. The preservation of their identities becomes a key element of this exhibition, as it uses material objects and linguistic resources to convey these narratives; likewise, maintaining this anonymity in the works serves to demonstrate the universality inherent in the stories depicted, emphasizing the shared experience.

MVO: The selection of artists allows us to draw a parallel (but convergent) history of contemporary Venezuelan art developed outside the country. How do you think the influence of seeing/living the migration phenomenon from abroad?

FRD: The influence is inevitable and substantial in the evolution of contemporary Venezuelan art. I think the geographical and cultural distance between us and our country of origin offers us migrants a unique view, and the opportunity to reflect on our identities, affiliations, loyalties and so on. We are in a distant but connected position. Finding ourselves outside our original environment, we are challenged to reinterpret and reconstruct our lives, often integrating new cultural influences and perspectives.

This positioning can also generate a broader and more global connection with new audiences; thus, the Venezuelan diaspora directly or indirectly shapes their experiences and reflections in art, contributing to transnational conversations about issues that we may not have previously understood, and that we are now developing, given that historically Venezuela did not have a considerable diaspora like the one we are currently witnessing. Therefore, contemporary Venezuelan art developed outside the country not only reflects the individual complexities of migrant artists, but also amplifies the voices of a dispersed community eager to encounter/re-ecounter themselves.

MVO: In the essay you wrote for the exhibition you make a difference between the notion of embodied objects of memory and the idea of material culture. Could you tell us about this aspect?

FRD: This is a concept that I have been developing based on observations and autonomous research projects, and which I presented in the framework of the 4th Symposium "(Re)Thinking Venezuela: Movement, Transit, Displacement" held at Cornell University in the spring of 2023. The distinction between the notion of "objects of embodied memories" and the concept of "material culture" focuses on the depth of personal connection that the former carry with them.

As a contrast to material culture - an anthropological term that refers to objects and artifacts associated with a particular group (jewelry, tools, art, architecture...) - objects of embodied memories comprise elements imbued with personal meaning and individual experiences. By this I mean things that have a unique and special meaning for the individual, regardless of their importance to the collective Venezuelan identity. These are things that may not be recorded and endure in the passage of history, but are integral parts of our own microhistories, even if they are not "anthropologically important" (and that is the point). For example: family photographs, letters, childhood toys, clothing... as they carry with them the memories and experiences of migrants. These objects are not necessarily representative of Venezuelan material culture, but they are witnesses and potential narrators of past lives and highly personal stories, highlighting the emotional charge of these objects and the threads between the singularity and universality of the narratives encountered.

MVO: Nostalgia is a feeling present in a notable part of the history of Venezuelan art. Do you consider that this feeling exists in the works that make up the exhibition Build what we hate. Destroy what we love?

FRD: I don't think that nostalgia predominates so much in the works of "Build what we hate. Destroy what we love", but rather an active process of documenting in order to recognize, and preserve in order to remember, both the memories of the artists and of the many unprotected people who have been affected by a process of forced displacement such as the one experienced in Venezuela.

It’s a bit complicated, because the works show us experiences of a very recent past (and that are still being lived) and it is like a wound that is still open. I think the artists make a great effort to bring to the collective conscience the migratory experiences and the challenges related to them, without becoming melancholic or longing for the past. The emphasis is on remembering, not only as a sentimental act, but as an action that invites us to reflect collectively, analyze the multiple layers of the migratory experience, and build shared stories that unite us in our separation. The commitment to memory implies not only reflecting on the past, but building connections with our present and future. It is an act of resistance in the face of oblivion and cultural homogenization, especially when the stories of those who are most vulnerable and neglected by oppressive systems are remembered and transmitted.

Build what we hate. Destroy what we love. will be open to the public until March 9, 2024 at 291 Church Street, New York, USA and online through the apexart website.