THE WIND OF HISTORY. THE FRAGILITY OF THE ANCESTRAL TIME

History forms an invisible rhythm, resounding in the background of visual stories. Listen carefully and the past will also reveal its intrinsic connection with the future. “Which of these two constructs is the driving force, and which sets the tone of the current moment?” asks "The Fragility of the Ancestral Time," a group exhibition first shown at Casa Velazquez in Santo Domingo and now on view at the Avèle gallery in Cap Cana. Bordering on philosophical treatises, the exhibition provides great aesthetic pleasures.

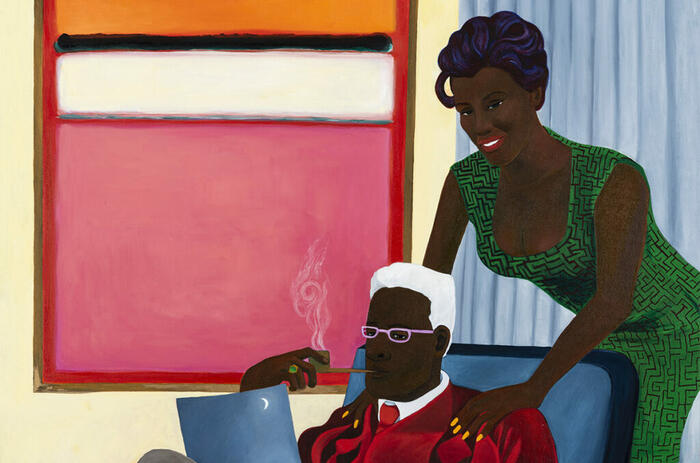

The bubbles on Olamide Ogunade's canvases are relatively small and, as bubbles tend to, barely stand out from the background; you have to strain your gaze to see them. They work like drapery or a curtain that almost disappears once the eye becomes used to the canvas and the viewer is drawn to the true depiction behind them: the glamorous world of women dressed in colorful clothes, overly stylish, immortalized in poses that wink at historical painting costumes. Like a refrain, the white circles of bubbles return in every Ogunade canvas. A touch of geometric abstraction in a portrait? Perhaps, but probably above all, a strong narrative statement: what is painted is a fleeting moment taken out of the stream of time, conceivably more meaningful than the moments of the great history of nations, continents, and cultures. This thought runs through the exhibition by the collective Heliconia Projects, created by Nicole Bainov and Elsa Maldonaldo-Buitron. It is also one of the first opportunities to see this unique set of talents in the Carribean. In addition to the fantastic Latin voices of Clara de Tezanos and Francisca Sosa López, the exhibition features Cecilia Fiona, the Danish experimenter with painting language, and Ogunade, from Nigeria. Curiously, these are stars of the new generation. Recently, Fiona was featured in the Danish royal collection and Sosa López showed her works at the British Museum.

The starting point for the story constructed by the curators is Walter Benjamin's notion of the historical past, which drives the present and equips it with meaning, but at the same time, pulls it back and prevents a true, unrestrained exit into the future. This is a thesis formulated by the philosopher when describing the "Angel of History," painted by Paul Klee in the 1920s. In the painting, the angel looks into the past, his back turned to the future, though it is towards the future that the wind of progress or the passage of time draws him. The curators recall this symbolic image by adding that nothing happening today could happen without being fed by the fluids of the past, the work of generations and traditions.

And yet, it appears Benjamin's position can be supplemented with a footnote from later studies of this topic, most notably "Retrotopia" by Zygmunt Bauman. Let us remember, when the future is inconvenient and cannot be predicted and controlled, the past becomes a source of hope and freedom. The retrotopias of the title are visions set in what is almost lost; they are on the verge of death and loss, but still able to rise from the ground and construct one's happiness and community identity. Composed of works by Sosa López, de Tezanos, Fiona, and Ogunade, the show takes us one step further. While Bauman writes about retrotopias as concepts belonging to communities, creating new political entities and sometimes populist ideas, the artists presented by Heliconia Projects talk about private worlds and personal visions of history, about what we could call "private retrotopias," idealized visions of the past marked by their history and their own point of view.

These threads are the axes that define the works of Sosa, an artist working with draperies--or rather, tapestries--that are nothing more than an assemblage of materials inherited from the family, such as old bedding and textiles used at home. The Venezuelan artist combines traditional weaving techniques, embroidery with beads, and mother-of-pearl, and transforms them into wall hangings that give voice to the material heritage and legacy of the techniques. Large-format objects hung on the brightly lit walls of Casa Velazquez and the exhibition spaces of Avèle gallery are substantial statements of Sosa’s interest in a private search of family history, marking the artist's subjective position.

This privacy of gaze is reflected also in the fantastic installations of de Tezanos, an artist who researches the play of light and the liminal situations created by sunlight. Prisms hung on one of the walls are an invitation to reflect on the titular transience and passage of time. Although a stream of light passing through the glass element of the installation is registered by the human eye as continuity and uninterrupted duration, it is nothing other than a journey in time. Passing through the border of the glass changes the course of the light and splits the stream into many colorful rays, seen differently by each viewer depending on the angle from which the sculpture is observed. A look into the future is individual and highly subjective, the artist seems to suggest.

Fiona’s works also include cosmogonic stories on canvas. In visually seductive works that formally resemble cutouts or puzzles, we detect notes of the transformation of human and animal figures. Scenes from Fiona's paintings resemble snapshots from a mystical dream. At first everything appears to occur simultaneously, but look more closely and a sequence of events seems to emerge. The viewer's eye combines them into a story about the eternal, repeating nature of the world or an adventure story written linearly in time--a neat visual reminder that time is just a construct and visual conventions known from primitive cultures can serve contemporary painting just as well.

The distinctive artistic voices evoked by the Heliconia Projects make up a curatorial story: imposed and solidified conventions of time and history lose their strength when confronted with the filter of creation and artistic transformation of the world. The featured artists break the tight framework of historiosophy with their elbows to suggest that we cannot be confined to one narrative and one view of the times, that private visions of history are more important than narratives about the historical moment introduced by communities and politics. It is a breath of relief in a world where we are conditioned to experience the zeitgeist in predetermined ways. Ah, once again we will be consoled by art.

The exbition is on view until Monday May 20th in Avèle Gallery, Cap Cana, Punta Cana 23203, Dominican Republic.