MAGOLA MORENO AND JOSÉ VIVENES: REPRESENTATIONS OF A POSSIBLE BLACKNESS

If the history of art is, to a certain extent, "the history of the complex infrastructure generated by the development of relations between artists and economic power" (López Zumelzu, 2020), when we are faced with works that subvert the canons established by tradition -and still belong to it- we may ask ourselves, how can we operate from within this framework to question the policies that constitute and decide what is made visible, and what is consequently made invisible?

Being part of this intricate structure implies understanding and accepting (or questioning and rejecting) the fact of being part of an establishment of selections and discards that every so often 'starts all over again'. Nevertheless, this recurrent tendency to restart allows us to scrutinize the framework and paradoxes established through historical discourses, finding in episodes such as the present an instance of critical revisitation, in which ethical precepts, structural concepts and inherited readings are questioned in order to make possible everything that, for a long time, has been condemned to absence.

However, in a rather contradictory way, in the midst of powerful transforming and vindicating movements, our present finds itself in a moment in which the market obeys one of the most conservative tendencies, founder in itself of the history we are referring to: the rise of painting, and in particular, of figurative painting.

Linked in a certain way to the return of these discourses made impossible by the homogenizing premises of the beginning of the Western twentieth century, the representational arts find in this moment of revision an opportunity to recover their current condition, despite the anachronistic nature inherent to painting. Thus, in a panorama largely dominated by representation and the citation of styles, a hyperbolic operation occurs that "is no longer even representation of imaginaries, but representation of representation" (Sanguino, 2024).

Making art inserted in the complexity of this context implies developing sharp intellectual mechanisms that make us think painting and the images it constructs, in such a way that it can traverse the intricate ethical paths of contemporaneity, made by the constant struggle between duty and power established by the margins of history, understood as "the space of emergence of possibilities, embodied in subjectivities endowed with power" (Berardi, 2019).

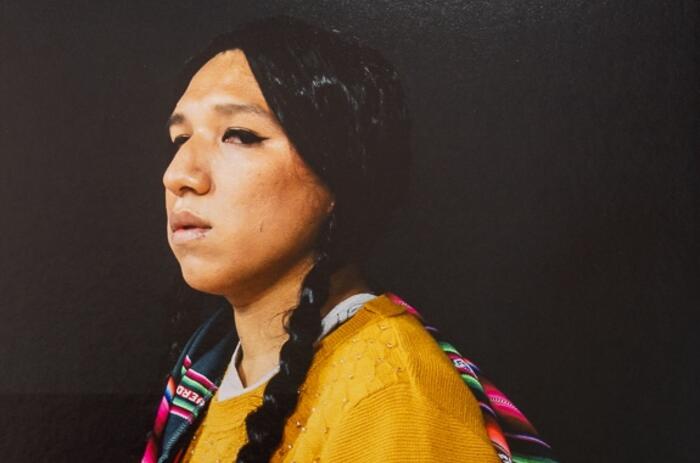

Thinking painting from its power to transform reality is a task carried out by artists such as Magola Moreno (Colombia, 1968) and Jose Vivenes (Venezuela, 1977), who, from their pictorial practices, have developed an interest in a 'representation of representation' subject to a plot twist: the insertion of black people in white-western historical imaginaries, characterized by their status of economic power. From different places of enunciation, both artists appropriate recognizable icons and silhouettes, assuming an inevitable critical position towards them. Thus, making use of the historical apparatus of portraiture and the desire for transcendence that gives rise to this pictorial genre, the images constructed by Magola Moreno and José Vivenes use the preconceptions of tradition (the pose, the clothing, the look, the setting) to represent a fictionalized reality, whose existence originates in the absence of itself, taking into account that "next to each thing that exists and can be seen, there is always another thing that cannot be seen, but is present" (Nuala, 2023).

Therefore, as a form of futurability, the representations of both artists are based on narratives that for a long time have privileged the white image -which in turn has fed and sustained many of the racist imaginaries and processes of whitening that are now being questioned- to offer a possible reality. Rejecting the customary underrepresentation of the anonymous, precarious or enslaved black people, Moreno and Vivenes' paintings offer a rearticulation and resemantization of recognizable symbols and discourses to present black people in positions of power, far from the idea of the 'black man who wants to be white' (in Fanon's words), but in a human condition that in itself poses a re-reading of the unjust historical narrative of humanity.

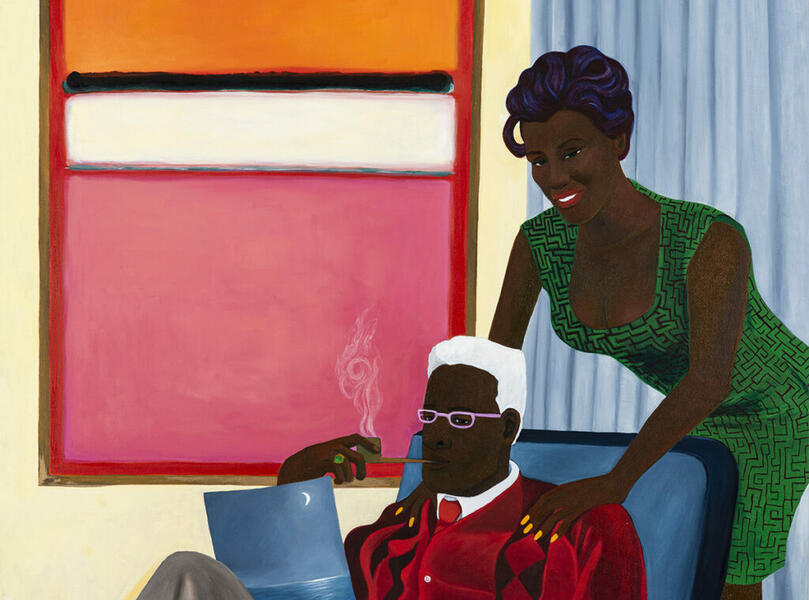

Originally, the portrait genre was the mechanism of maintenance of choice for artists in the Modern Era, a period in which, through the power of the image, patrons achieved a symbolic manifestation of their dominion and transcendence. This system of capital exchange appears as one of the many links in the relations between artists and the economy that shape the history of art, from which there would be a "succession of discourses that deal with whites, from whites and exhibited in white cubes" (Simões, 2023). All this framework underlies the series Art Lovers (2020-) by Magola Moreno, in which the artist portrays fictional characters who enjoy a privilege historically associated with the upper classes: collecting and enjoying art.

Situated in environments of domestic appearance, Moreno's paintings offer a rearticulation of signs and a clear citation of works that obey the deliberate interests of the artist, who in turn develops her own language through gestures and details such as the two-dimensionality of her backgrounds, the incorporation of graphic patterns in textiles and the distortion of anatomical proportions; which together, make up a painting designed to point out the canons, roles and stereotypes of the portrait of traditional society, through the alteration of its pre-established values.

Her work, made and thought from the Colombian Caribbean, responds to a context in which the 'Afro' heritage is present in the national imaginary, through a disseminated representation, which assimilates the primitivist projections that satisfy the taste of those who acquire them. On the contrary, Magola Moreno's work is located in scenarios that understand race as a mere fictional construction, returning a possible humanity to these characters who pose, embrace, relate affectively and show emotions distant from the exotic (erotic, voluptuous, carnal) or costumbrista (exploited, marginalized, poor) image to which the black figure has been historically marked.

Thus, by incorporating into the representational space of the painting a series of emblematic works by artists such as Fernando Botero, Beatriz González or Mark Rothko (and citing them as gestures of meta-painting), Magola's work puts into a possible context a whole history of art thought from the perspective of power: who can access these images and under what logics are they used, what historical economic structures have allowed the acquisition and storage of capital, and in whose hands is it, and finally, who has the possibility of making art a luxury?

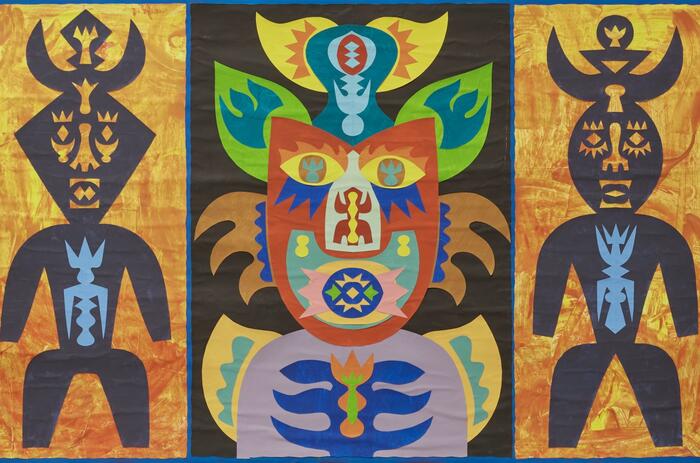

On the other hand, and continuing with an idea already exposed, endowed with symbolic values ranging from the cultural to the religious, the image of Western power has manifested itself to a great extent through the portrait genre. Aware of the power of the image and of the discursive apparatuses of history, in the painting of Venezuelan José Vivenes, the artist revisits and reveals the heritage of colonial imaginaries to build a syncretic image, in which, through appropriations and symbolisms, Vivenes' paintings position themselves in the face of power; in this case understood as "the selection and imposition of one possibility among many, and the simultaneous exclusion -and invisibilization- of many other possibilities" (Berardi, 2019).

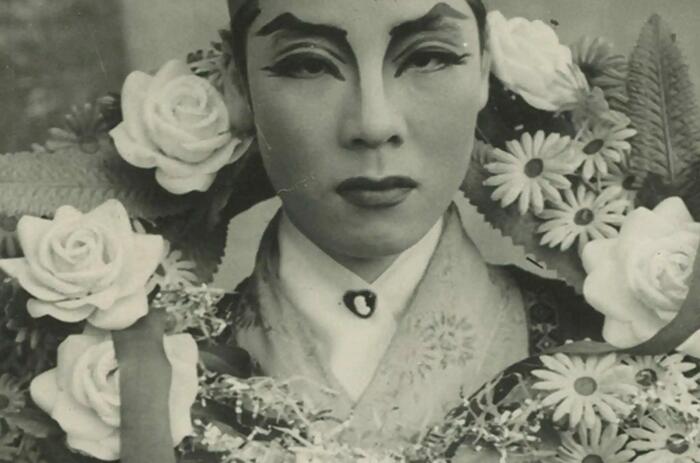

To exercise power, however, violence has been one of the most used mechanisms in any process of domination and subjugation; that is why Vivenes' images offer through his gestures, stains and strokes a technical metaphor (typical of painting) of the force used in the construction of a colonizing discourse, in which the artist resorts to black figures dressed in martial and bourgeois costumes (alien to any African culture) to create portraits of an impossible past, whose ironic signaling presents us with an imaginary futurization: A world in which the colonized are now the colonizers.

Following an appropriationist logic, Vivenes' operations "are not only about replacing the meaning of each image, but about remaking it, meaning that each image and procedure becomes the mirror of the same procedure and the same image" (Guasch, 2000); therefore, implementing a semantic transformation whose reflection-meaning is now inverse, substantial and elusive of any tangible reality. In this way, in the rearticulation of the imaginaries proposed by Vivenes, the African characters make use of ornaments that, understood as racial codes, remind us that race is prevalent not only as a concept, but also as an imaginary of the identity of a dehumanized subject, "who has found in language and in the image a euphemistic way to exist without responsibility" (Mbembé, 2016).

But how can black representation exist in painting while assuming the responsibility of moving away from stereotypes, of not making an exotic impression, and of not ending up in a white cube being looked at by white people? How can these images offer something more than the 'representation of a representation'?

By presenting scenarios that subvert the traditional reading of white history, the paintings of Magola Moreno and José Vivenes make possible the impossible, reminding us that just as representation depends on reality, it is also possible to conceive reality through its various forms of presentation. However, in the ironic nature of these artists' appropriation and citation of history, their works allow us to glimpse a hard certainty: that "the postcolonial world will not imitate or reproduce that which was realized elsewhere" (Mbembé, 2016), and that the desired future lies far beyond its representation.

By presenting scenarios that subvert the traditional reading of white history, the paintings of Magola Moreno and José Vivenes make possible the impossible, reminding us that just as representation depends on reality, it is also possible to conceive reality through its various forms of presentation. However, in the ironic nature of these artists' appropriation and citation of history, their works allow us to glimpse a hard certainty: that "the postcolonial world will not imitate or reproduce that which was realized elsewhere" (Mbembé, 2016), and that the desired future lies far beyond its representation.

References:

Berardi, Franco (2019): Futurabilidad: La era de la impotencia y el horizonte de la posibilidad. Buenos Aires, Caja Negra.

Guasch, Anna María (2000): El arte último del siglo XX: del posminimalismo a lo multicultural. Madrid, Alianza Editorial.

López Zumelzu, Víctor (2020): ¿Qué tan libre es el arte: La práctica artística en la cadena capitalista de generación de (otro) valor, en: Rotunda. Available online.

Mbembé, Achilles (2016): Crítica de la razón negra. Buenos Aires, Furor Anterior Ediciones.

Nuala, Ariana (2023): Reis Malunguinho: Na mata só tem um, en LA ESCUELA___. Available online.

Sanguino, Jorge (2024): Quo vadis pintura, in Esfera Pública. Available online.

Simões, Igor (2023): Dos Brasis: Arte e pensamento negro. São Paulo, Sesc Belenzinho.