LUCIO FONTANA. IL Y A BIEN EU UN FUTUR - UN FUTURO C'É STATO

Lucio Fontana made one of the most extraordinary and radical gestures of modern art in 1958 when he cut the surface of a monochromatic canvas with a razor blade. The exhibition “Il y a eu un futur- Un Futuro c'é stato” at the Musée Soulage, Rodez, revisits the legacy of this artist and offers a survey of his entire oeuvre, before and after the war, in Argentina and Italy.

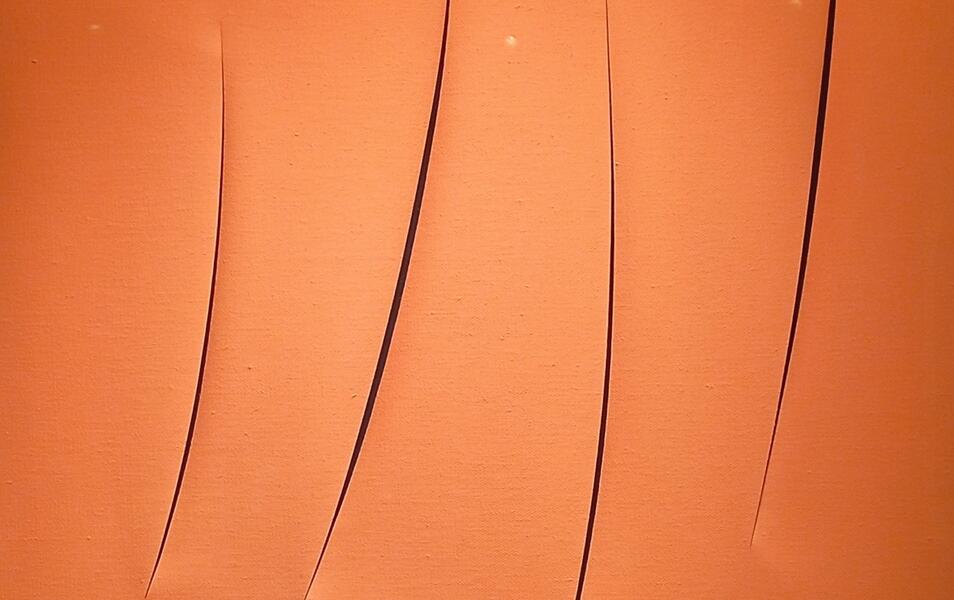

The exhibition, produced in collaboration with the Fondazione Lucio Fontana, highlights the diversity of his creation, between abstraction and figuration, metaphysical research and incarnation, utopia and kitsch, technological fascination and formless materials. Through a selection of more than 80 works, the exhibition goes through all his great cycles: primitive and abstract sculptures, drawings, polychrome ceramics, spatialist works, perforated canvases, informal works, environments, Tagli, Nature, Fine di Dio, Venezie, Metalli, Teatrini, etc., oscillating between the refined conceptual gesture and the profusion of materials and colors that play with the decorative. The public will discover beyond the Concetti Spaziali, with the Attese and the Buchi, a figurative and informal artist, a classic and futuristic man and it will be the opportunity to admire two Ambienti spaziali, that of the neon lights with curved lines, the arabesques of the IX Tiennale in Milan-1951-, recreated especially for the exhibition, and that of the Galleria del Deposito in Genevé-1967-. Curated by Paolo Campiglio and Benoît Decron, the exhibition is based on the concept of intuition of the future in Fontana's work, of the renewal of the status of art, to present a singular journey centered on the idea of dialectical oppositions between the material and the immaterial, on the concept of utopia assuming a contradictory relationship, of attraction and repulsion, in the face of concrete reality.

Fontana (Rosario, Argentina 1899 – Comabbio, Italy 1968) was the son of Lucia Bottini of Swiss Italian origin, and Luigi Fontana Italian sculptor of funerary monuments. Although as a child he was taken to Italy, where he was able to participate in the First World War, he returned to Argentina at the age of 22, working actively as a sculptor for more than seven years. He returned to Europe around 1928, where he spent the thirties and forties in France and Italy, worked as a sculptor, held his first exhibitions and collaborated with expressionist and abstract painters; he worked with avant-garde architects, while investigating new plastic forms using various materials. At the outbreak of World War II, Fontana took refuge in Argentina, his native country, where he opened a sculpture workshop.

Although he is best known for his paintings, Fontana was initially trained as a sculptor, and his career in this field explains his incessant interest in the notions of surface and dimension. Thanks to his perseverance, Fontana's techniques were perfected, leading him to go beyond the commercial styles he was used to producing. He stood out as one of the most innovative sculptors of his time, especially in ceramics, working and researching new plastic forms, using various materials, including terracotta, bronze, porcelain and even reinforced concrete.

In Buenos Aires, Lucio Fontana founded the Altamira Academy with Argentine colleagues and there he gathered around him a group of young students with whom he published, in 1946, the White Manifesto, in which he outlined the theories and ideas that gave shape to the spatialist movement that inaugurated a new stage in his artistic career. By formulating his ideas on artistic research, he defined a new art and rejected the old traditions. After the war, Fontana returned permanently to Italy where he continued to explore the ideas of spatialism; as he explained in his White Manifesto: the main idea of spatialism was to create an art form that synthesized sounds, colors, movement and space in a single work. In 1947, back in Milan, he created the artists' group “Movimento Spaziale”, published two manifestos and established himself as one of the most important avant-garde artists of the first post-war generation. From 1949 his researches conclude in the generic denomination Concetti Spaziali perforated, also called Buchi, gathering sculptures and paintings through which he tried to overcome the physical limits of the work of art and its materiality to reveal its absolute. This research leads Lucio Fontana to insert emptiness into the compact matter that constitutes his work. He thereby uses the canvas as a screen whose perforations open onto a transcendental and cosmogonic experience. Spazialismo aims to create a form of art that does not respond to academic codes, but seeks to go beyond simple colors fixed to a support; in fact it responds to a society in full change, concerned by spatial discoveries and a new modernity.

Fontana was obsessed with the conceptual dimension of art, which he perceived as an instrument of research rather than a simple aesthetic questioning. In fact, Fontana said that he did not want to paint, he wanted to “open a space,” “a new dimension.” These innovations opened up new perspectives for artistic research, foreshadowing the major artistic movements of the 20th century, such as Arte Povera, Abstract Expressionism, the Zero Group and Minimalism.

At the end of the 50's, after a process of reduction to monochrome, Fontana completes his cycle of tagli. Subtitled Attese, the Concetto Spaziale series is the artist's most famous one. These meticulously cut monochromatic canvases initiated the “Tagli” period, breaking with the informal and random gesture of his earlier “Buchi” phase. By piercing and lacerating his canvases, Fontana goes beyond the materiality of their support. The canvas is no longer a flat surface but a three-dimensional object; he uses the cuts to suggest an idea of openness and emptiness, to offer a concrete experience of space. The painting itself becomes obsolete, which makes the creation of the work no longer additive but subtractive; it breaks with the illusionistic tradition associated with painting, the sacred canvas is so to speak violated. The shadows really appear on the canvas and are no longer simply simulated by mimesis. The idea of the future, which Fontana inherits from Futurism, is that of an art liberated from the traditional categories of painting and sculpture that is increasingly immaterial as an act.

Reconstructing Fontana's thought is an arduous task, though not a difficult one, since he is an artist who has written and traveled extensively and conceived numerous interviews; we can therefore consider him not only as the first and most important of the spatialist artists, but also as their theoretician. Clairvoyant, frank, Fontana was a multifaceted artist, current, cultured, knowledgeable of art history; he is the reference of the Italian artists of the 1950s and a model for the avant-garde of the 1960s. His “Buchi” and “Tagli” are often puzzling, sometimes provoking the perplexity of those who discover them; however, few works have been so revolutionary, their value does not lie so much in the technical simplicity of their creation - which in any case is only a presumption - they were born after a very elaborate process. Through his art, Lucio Fontana considered himself satisfied to have had the intuition of the eternal contradictions between the material and the non-material, to have worked on the idea of the infinite, foreseeing that someday the human being would find his destiny there.