THE BRITTLE POSTCOLONIAL PROPOSAL OF GRADA KILOMBA

The Reina Sofia Museum presents in the exhibition Opera to a Black Venus a necessary journey to the work of Grada Kilomba (Lisbon, Portugal, 1968), forming the most complete exhibition of her work to date in Spain. The Portuguese artist presents a complete discourse, mainly expressed through the different languages of movement, from the body to performance, but without leaving aside other narrative and artistic techniques with which she analytically presents a certain introspective look at the world of history.

Within the ideological approach of the museum's proposal, Kilomba's postcolonial story seems to fit perfectly and decides to braid itself in that wide range of technical and academic possibilities to reinforce the political tendency. It is worth asking here if that analysis that underlies the Portuguese artist's work, whose main object is the production of knowledge to engage in a process of unlearning hegemonic narratives, collides head-on with a reality in which her idea has become an institutional mantra, underpinning that hegemonic narrative that seems to make up the ideological system in today's Spanish museum system.

For this reason, Opera to a Black Venus must be observed from a critical point of view in two areas, the aesthetic and the ideological, being able to analyze the calology of its approach against the discourse embodied. It might seem incomprehensible from an analytical point of view, since the homogeneity of its proposal becomes a unique element, but it is susceptible to be unfolded in its double intention.

Kilomba poses several scenes to highlight in them the transcendence of colonialism, climate change or the impact of immigration. “What would the bottom of the ocean tell us tomorrow if it were emptied of water today?”, a phrase that accompanies the title of the exhibition, starts from that very idea, that of the symbolic scenario of the effect of historicist discourses that it aims to rewrite.

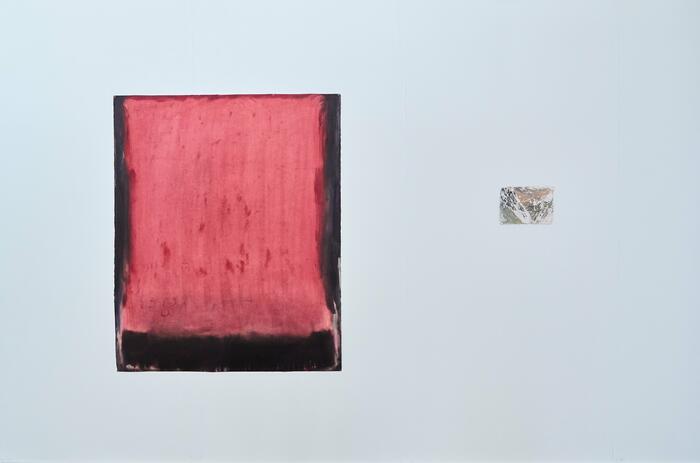

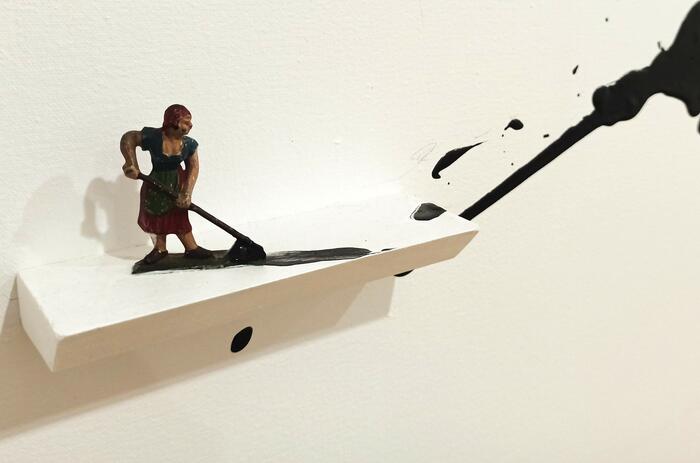

Opera to a Black Venus (2024 - in progress), the large-scale video installation that presides over the first room, constructs the beginning of a contemporary opera dedicated to a black Venus that resides at the bottom of the ocean and becomes a sort of oracle that watches over resistance and memory. In this same dynamic of the maritime imaginary, the artist directs the public towards the consolidation of this space of reference through other installations and actions that complement this main opera. Therein lies the strength of works such as 18 Verses (2022), Sounds of Water (2023), Labyrinth (2024) or Compressed Time (2024), which together with The Desire Project (2016) and Table of Gods (2017) complete the possibilities of expression.

However, beyond the meritorious aesthetic impact that harbors the discourse of the aforementioned works, perhaps the most critical point of the exhibition is the video installation A World of Illusions (2017-2019), a renowned trilogy by the artist in which she reinterprets three Greek mythologies from a postcolonial point of view: Illusions Vol. I, Narcissus and Echo (2017), with a focus on invisibility; Illusions Vol. II, Oedipus (2018), dedicated to violence; and Illusions, Vol. III, Antigone (2019), oriented to remembrance and mourning.

In it, Kilomba runs through the myths as a pointer, leaving the aesthetic protagonism to the group of artists who symbolize the critical points of the narrative. However, it can be seen that the Portuguese artist's proposal constantly incurs in conceptual contradictions. The narrative, or counter-narrative, that allows the exhibition to be articulated in this work refers us to a continuous division that pretends to fight from the division itself.

Starting from the intrinsically economic and postcolonial action of articulating everything in a language such as English, whose character of current lingua franca in part of the West does not hide a past that allows it to continue acting as colonialist in the present, Kilomba continues to propose partial fields of discourse, focusing his Afro-European critique on the white, habitual West, but at the same time circumscribing all history to that of the same, obviating the slavery and proto-colonial Arab processes in East Africa.

To pretend to recognize the idiosyncrasy of a people in an erased history by eradicating everything that allows to specify a general radiography of the people in question is to fall exactly in the error of what it describes or it is tried to advocate. And even more so if what is intended is to reread, textually, correctly. Is there a concrete guideline for a revision, rereading or reinterpretation to be correct, as encouraged by the Portuguese artist? Perhaps Kilomba leaves aside that the answer lies solely in the institutional, which is the source of all historicism.

There is also a conditioning factor in the selection of pieces of mythology and classical literature to use them instrumentally to disarticulate a historiographic discourse. We could ask ourselves to what extent one is coherent when one tries to redraw the history of a people or of certain policies, not only by presenting it in a fully colonialist language, but also from a cultural point of view and an extemporaneous gaze that is totally alien and that implicitly seeks to discredit.

The possible contradictions in Kilomba's counter-narrative are not unique among those who serve the process of decolonization in the Western institutions, but neither should we disregard the fact that there is a wide margin for falling into these inconsistencies, since the implicit rereading of history has its origin in the reading that has been made of it. That is to say, at no time does it start from an original point on which to act, but what is attempted is to patch up on what already exists, on what has been said, on the discourses, that is to say, on that historicism that has circumstantially become institutional.

The fact that we find in Opera to a Black Venus could find its meaning in that museographic and institutional decolonization, given that it is precisely circumscribed to a political environment, although flirting with the very constricted margins of any narrative makes it easy to contradict. Ultimately, it should serve us to debate whether decolonizing tendencies have to build on what is already constructed or whether, on the contrary, they can have a critical complementary action in which comparative and dialogue can lead us to a much more adequate truth than what is intended by certain antithesis narratives.

Opera to a Black Venus: What would the bottom of the ocean tell us tomorrow if it were emptied of water today? can be seen until March 31 at the Reina Sofia Museum, Santa Isabel, 52, Madrid (Spain).