FERNANDO ALLEN AND CONFINES OF PARAGUAY IN PINTA BAphoto 2024

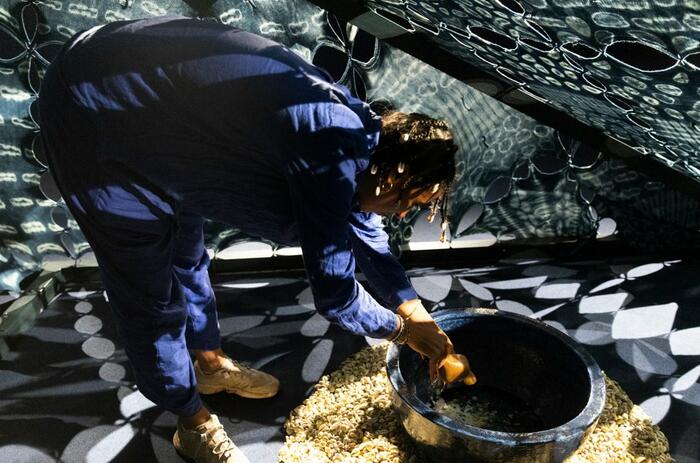

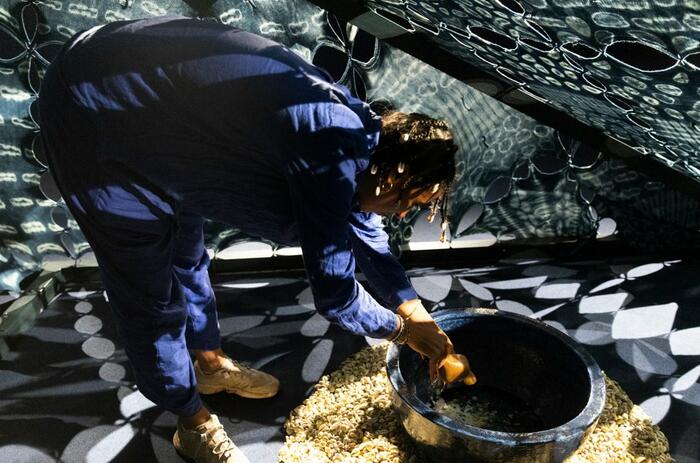

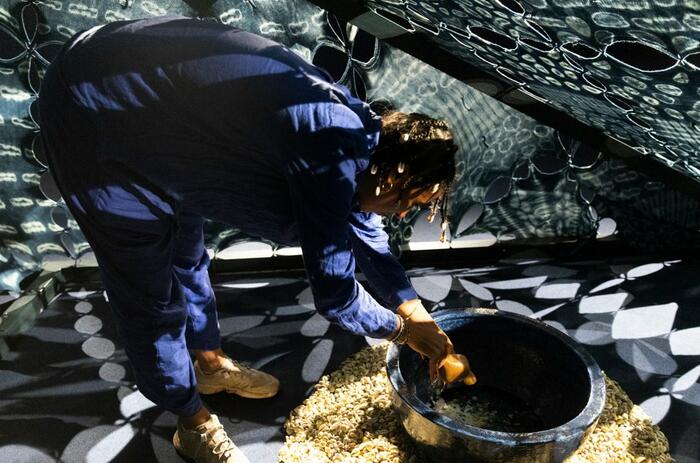

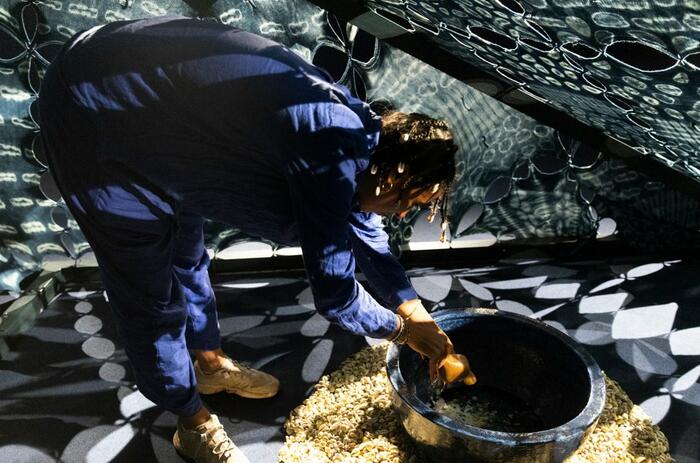

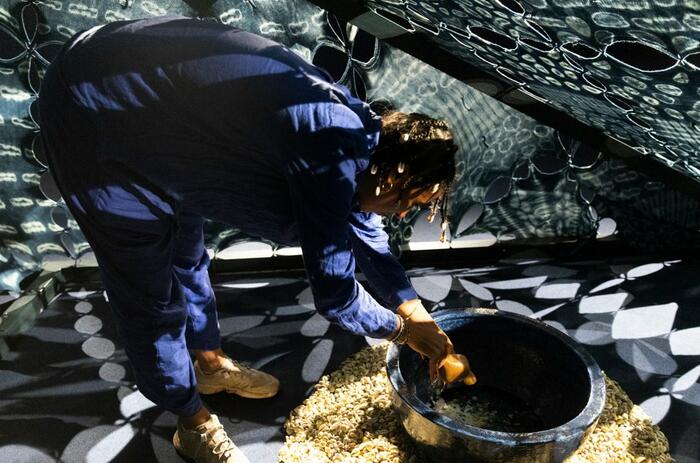

Confines of Paraguay is the initiative of Fernando Allen and Fredi Casco that is part of the Main Section of Pinta BAphoto. It is a project that began with a photographic approach, but expanded into an editorial, audiovisual and documentary archive -along with other activities- related to the works of popular and indigenous artists from Paraguay.

How did the initial idea for Confines del Paraguay come about and how has it evolved over the years?

The idea came about 15 years ago, when we thought it was a good opportunity to systematize the photographs we were collecting from our trips to the confines of Paraguay in search of images of the cultural frontiers. At first it was going to be a purely photographic project. In 2012 we were contacted by Martin Nasta to carry out the curatorship of “Texo Selection 2”, which was called “Masters of popular and indigenous art of Paraguay”. Texo wanted us to form a collection, and later, to organize an exhibition. It was an extraordinary experience; for months we traveled around the country to select and work with popular and indigenous artists. The exhibition was held at the Juan de Salazar Cultural Center of Spain in 2013 and the following year at the Maison de l'Amérique Latine in Paris.

Later, the Fondation Cartier of Paris asked us to work on a collection of popular and indigenous art from Paraguay for them (a collection that has been growing over the last ten years) and so we also began to form a collection of our own, with the cultural treasures that we were finding along the way. At that time there were already extraordinary collections such as the Museo del Barro and others such as Verena Regehr's in the Chaco, and Ysanne Gayet's in the city of Areguá. We join these efforts to rescue and conserve the symbolic material and immaterial production of our country.

What was the process to create the collection of popular and indigenous art that Confines del Paraguay has today? What challenges did you face in the collection of pieces and the organization of the project over the years?

Sometime before the Confines del Paraguay project, each of us -Fredi Casco and I- had been acquiring pieces of popular and indigenous art, especially ceramics and masks, on our own. This practice, almost instinctive at the beginning, evolved into more concrete actions, such as the systematic acquisition of works made in different techniques (carvings, textiles, ceramics, paintings, drawings, etc.), almost always linked to an editorial or audiovisual project. The challenges we face are different according to the regions of Paraguay in which we work.

In the Chaco, where we develop almost all our projects, the difficulty of access to many communities is one of the main problems. The increasing lack of primary materials (such as caraguatá, or chaguar, whose fibers are used to make the threads for textile pieces) is also a major problem, since in several communities, women have stopped weaving because of this. Something similar happens with the wood of the Palo Santo, a tree used by artisans of various ethnic groups to make carvings. These issues are closely linked to the process of territorial exclusion produced by the expansion of agribusiness (massive deforestation, acquisition of hundreds of thousands of hectares by national and foreign landowners with the consequent migration of the ethnic groups that used to occupy them, etc.). This is in terms of material challenges. There are a host of other factors that shape the symbolic production and therefore affect the process of acquiring diverse pieces and works.

How do you balance the representation of the traditional practices with new forms of artistic expression within indigenous and popular art in your curatorial practice?

Generally speaking, there is a tendency to think that only “pure” or “ancient” manifestations of indigenous and popular art are those that have authentic cultural or artistic value. A spectacular ceremonial costume of the Ishir ritual called “Debylyby” (which can be seen in the Museum of Indigenous Art of the CAV/Museo del Barro), is far from those that are made today in the community of Puerto María Elena (Alto Paraguay), the same one that 3 or 4 decades ago, produced that one for the same ritual.

We believe that as long as these communities manage to maintain, in one way or another, the concepts on which these symbolic expressions are based, the current materials (plastics, cans, cotillion masks, masks made of cardboard or printed fabrics, etc.) that complement or substitute the old elements found in nature, are a practical way of survival and adaptation to the circumstances in which they live. This issue occurs, with some differences of tonalities, both in the world of popular peasant art, as well as in the indigenous.

What is the proposal exhibited in the 2024 edition of Pinta BAphoto about?

The proposal of this exhibition is structured around the concept of deception, or delusion, in four series that we present.

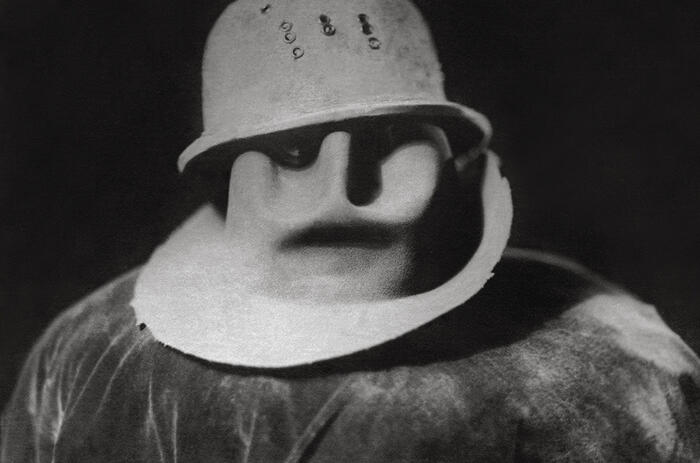

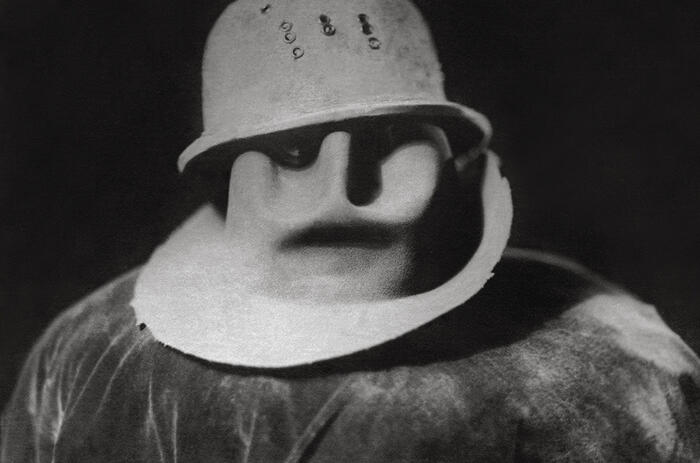

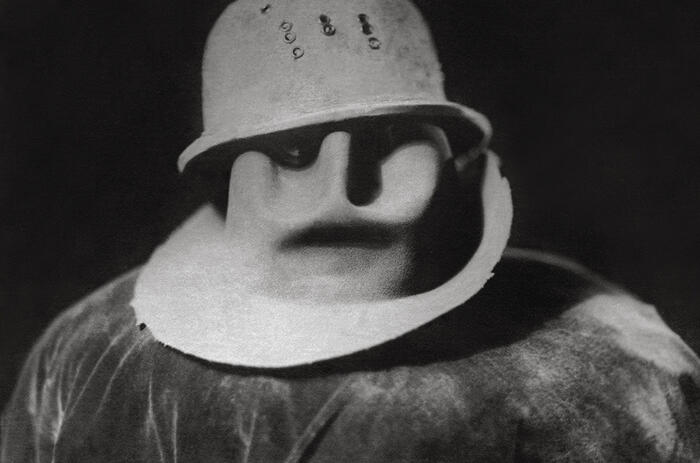

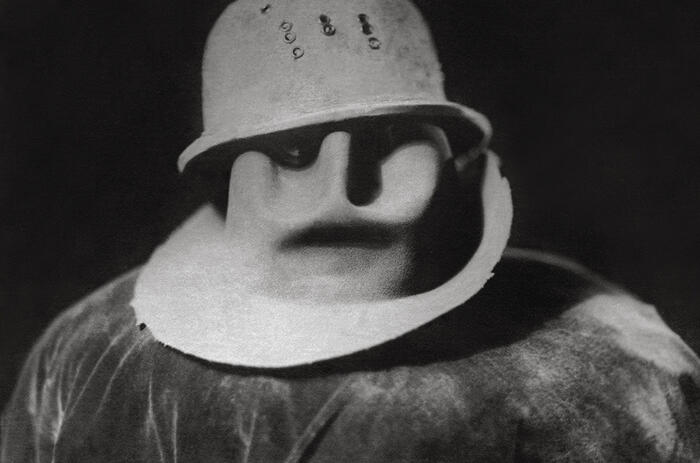

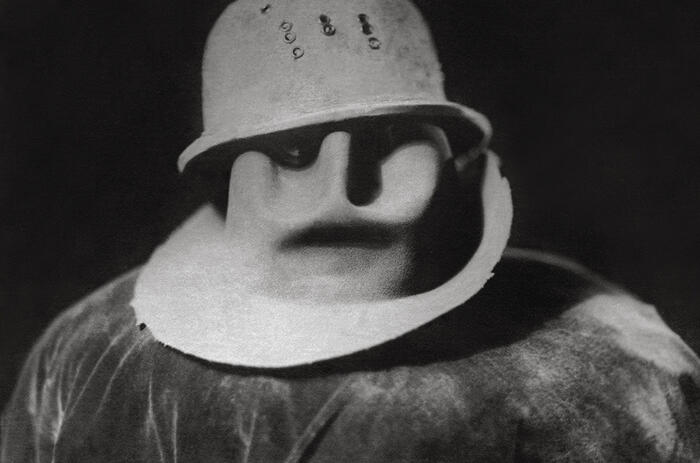

The ritual of the Ishir ethnic group, from the great Paraguayan Chaco, called “Debylyby”, which consists of the representation of the great founding gods of the Ishir culture: the Anábsoro. The ritual is born in the night of the times, from a curse, the one pronounced by Nemur, one of the most powerful gods of the Ishir mythology, which condemns the Ishir to periodically represent their gods, the Anábsoro, whom they themselves have exterminated, under penalty of the extinction of the whole race. These symbolic games must be carried out without the women of the community being aware that the real gods have disappeared, being the men who, wearing clothes and beads similar to those used by the gods, take their place in the sacred ceremonial spaces.

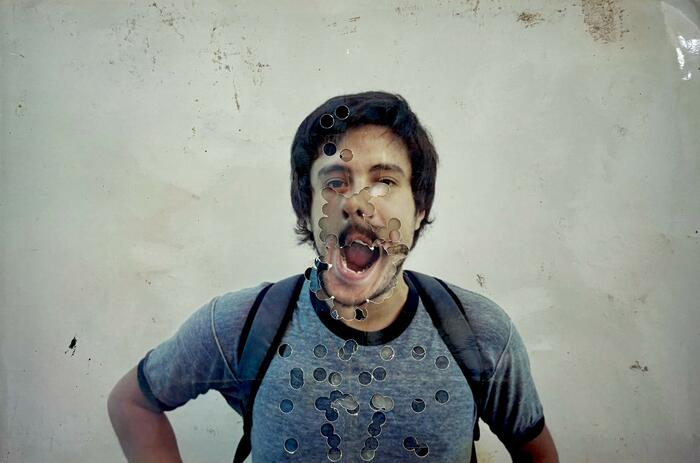

The Guarani ritual of the “Arete Guasu”, or “Kandavare” (the name given to it in the town of Pedro P. Peña), developed only in distant territories of the Paraguayan, Argentinean and Bolivian Chaco. The main characters of this staging are called “Agüero Güero”, and represent the deceased members of the community, who return during the days of the ritual to dance and share a magical time with their relatives.

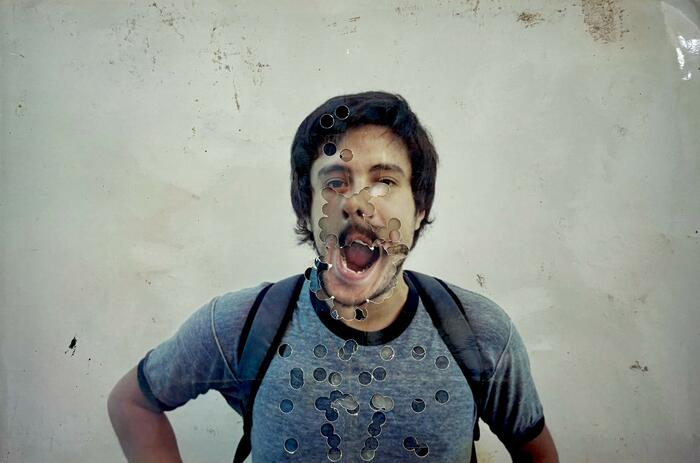

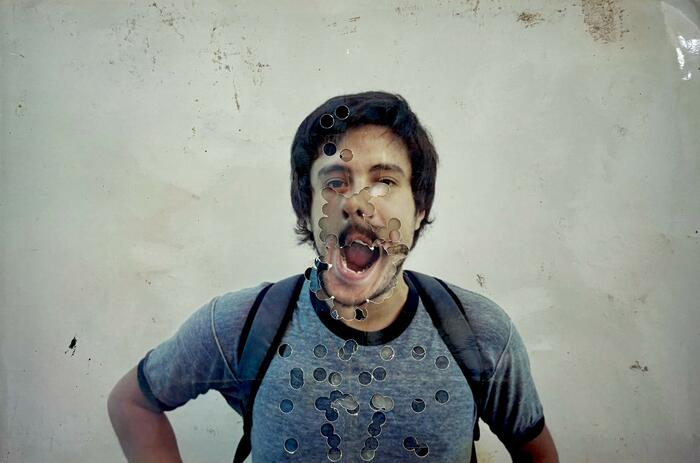

The popular festivities known as “Kambá Ra'angá”, in which masks made of light wood (timbó root, preferably) are used, and in which the members of the peasant communities where they take place, assume other personalities hiding behind these artifices (masks, old clothes, costumes made with chicken feathers, or with dried banana leaves), their daily identities.

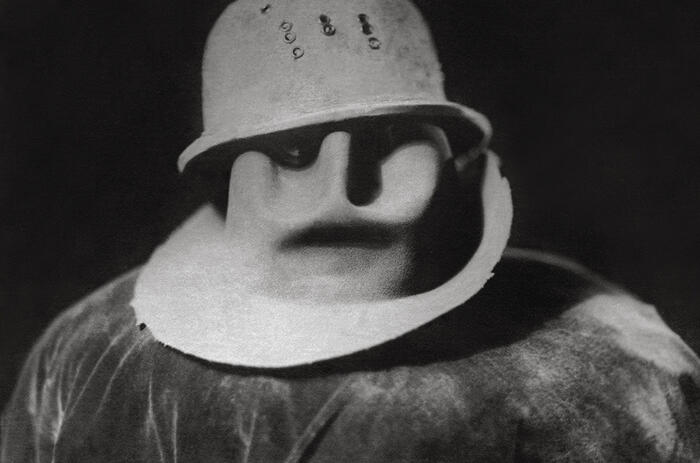

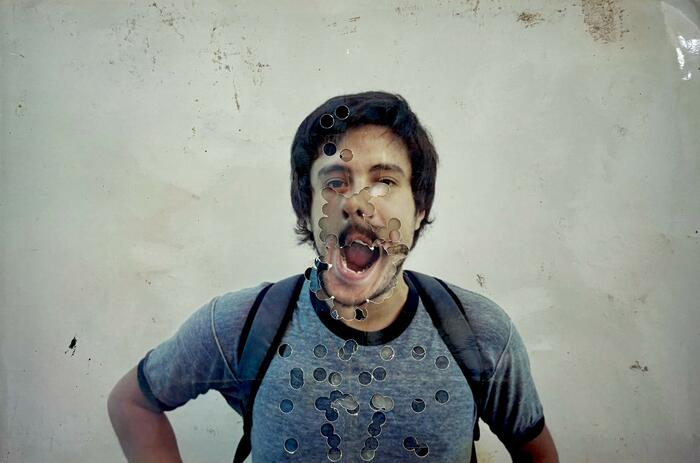

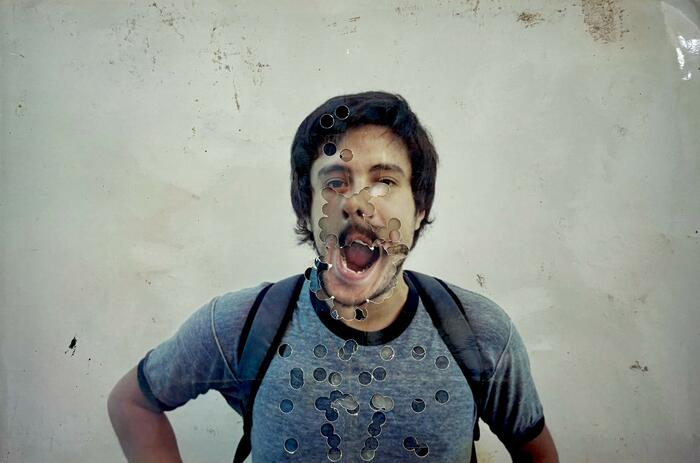

The case of Nicolás Benítez. A boy originally from a town in the interior of Paraguay (Itá), the only son of a single woman (almost a cardinal sin in the conservative Paraguayan society, mostly Catholic) whose circumstances pushed him to leave the country, first, and then to build the enigmatic and fascinating character he would become: the pai of Santo Kola í, or Pai Nicolás, as he is known today. His patron saint, to whom he dedicates his efforts, is Saint Death, an apocryphal saint, not recognized by the Catholic Church, but who nevertheless has a legion of followers in Paraguay and Argentina.

In these four cases, the devices that shape and sustain the respective rituals or representations are designed to deceive (Ishir case); to mock time by making improbable returns possible (Guarani case); to exorcise the fear of the “other” (the enemy, perhaps), assuming different faces (Kambá Ra'anga case); or to transform into a character such as Pai Nicolás (a popular version of the superhero) whose direct relationship with the cult of the disturbing Saint protects him against the prejudices of a conservative society that fears the other, the different.

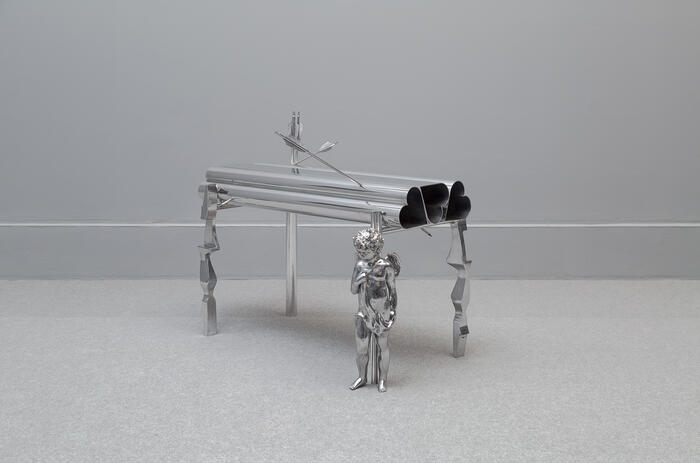

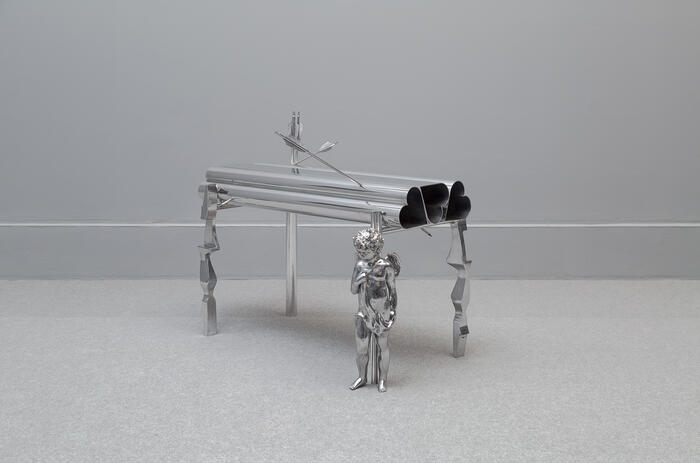

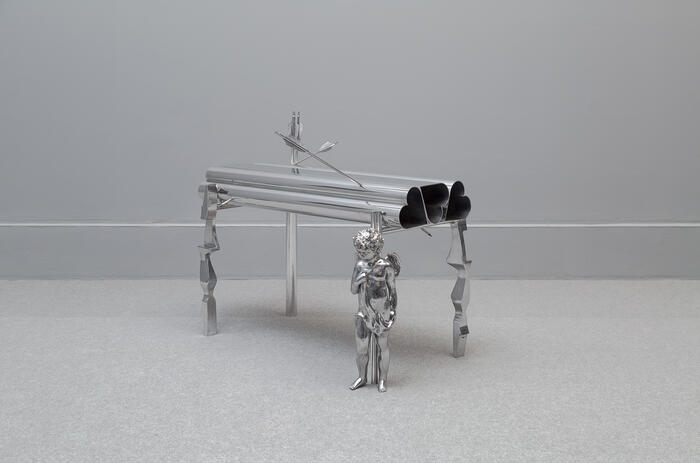

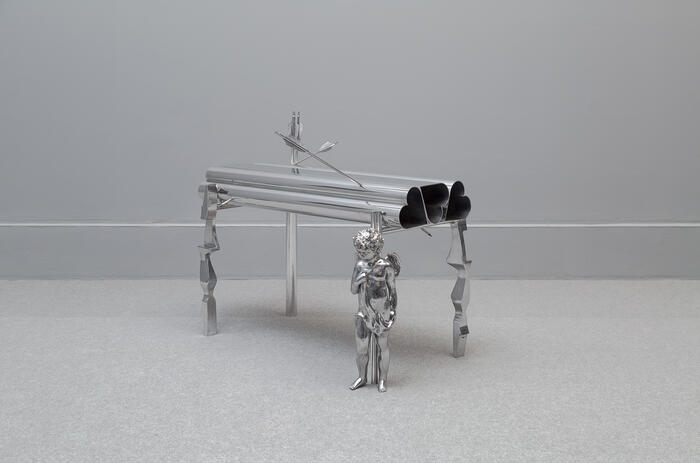

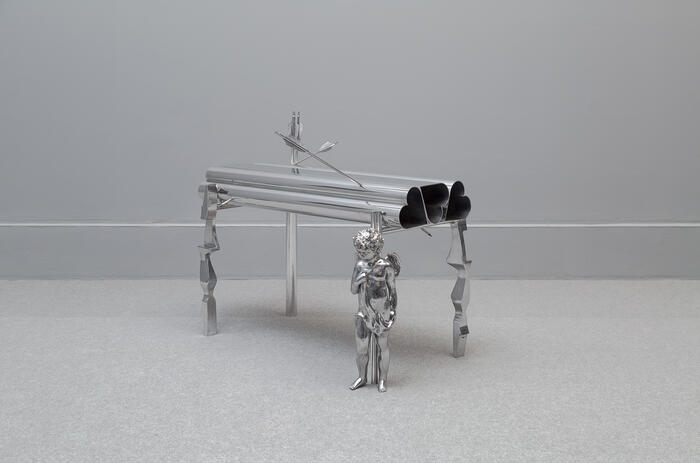

Together with these photographs we present, as a context, some objects that have a direct relationship with these cases: a ritual costume of the Kambá Ra'angá, two masks of the same ritual, a carving of San la Muerte made by the carver Aquiles Copini, a popular painting (acrylic on wood).

What are your long-term expectations for the future of popular and indigenous art in Paraguay? What do you hope this project will achieve in the coming years?

First of all, to give this issue the relevance it deserves: that although there is the market, where these treasures often become merchandise or cultural fetishes, the material and symbolic production of the native peoples cannot be reduced to just that, to a market phenomenon. The sale in the market helps to more or less sustain the artists, but it is far from enough. Society has to understand that we are facing an extraordinary cultural richness that runs serious risks of disappearing. All this must be put in context, not only through dissemination, but also through education, in schools, universities and museums.

In this sense, Confines del Paraguay is not only a collection of objects, we have also produced half a dozen audiovisual documentaries, in addition to the photographic record. Likewise, we constantly carry out social actions for the benefit of the artists' communities, such as donations of food, clothes, medicines, construction materials, help for medical consultations, and all kinds of collaboration that we manage to articulate in our circle of private action.

Pinta BAphoto 2024. October 24-27, 2024. La Rural, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Related Topics

May interest you

The Tribute Artist section of Pinta BAphoto celebrates a decade exhibiting the trajectory of photographers who had an active participation in the field, seeking to recover and value their figure. This edition, curator Francisco Medail presents Jaime Bolotinsky, a Russian-born photographer based in Buenos Aires who was a pioneer when it came to composing his portraits, using everyday elements and a precise handling of light.

JAIME BOLOTINKSY'S EVERYDAY ELEMENTS - TRIBUTE ARTIST AT PINTA BAphoto 2024

The Tribute Artist section of Pinta BAphoto celebrates a decade exhibiting the trajectory of photographers who had an active participation in the field, seeking to recover and value their figure. This edition, curator Francisco Medail presents Jaime Bolotinsky, a Russian-born photographer based in Buenos Aires who was a pioneer when it came to composing his portraits, using everyday elements and a precise handling of light.

The Tribute Artist section of Pinta BAphoto celebrates a decade exhibiting the trajectory of photographers who had an active participation in the field, seeking to recover and value their figure. This edition, curator Francisco Medail presents Jaime Bolotinsky, a Russian-born photographer based in Buenos Aires who was a pioneer when it came to composing his portraits, using everyday elements and a precise handling of light.

JAIME BOLOTINKSY'S EVERYDAY ELEMENTS - TRIBUTE ARTIST AT PINTA BAphoto 2024

The Tribute Artist section of Pinta BAphoto celebrates a decade exhibiting the trajectory of photographers who had an active participation in the field, seeking to recover and value their figure. This edition, curator Francisco Medail presents Jaime Bolotinsky, a Russian-born photographer based in Buenos Aires who was a pioneer when it came to composing his portraits, using everyday elements and a precise handling of light.

Pinta BAphoto celebrates its twentieth edition at La Rural, consolidating itself as one of the most important fairs dedicated to photography in Latin America. This annual event brings together galleries, artists and collectors, and throughout its two decades, it has been an essential platform for the development and dissemination of photographic art, both locally and internationally.

VISUAL CONFLUENCES - NEXT | Out of Focus AT PINTA BAphoto

Pinta BAphoto celebrates its twentieth edition at La Rural, consolidating itself as one of the most important fairs dedicated to photography in Latin America. This annual event brings together galleries, artists and collectors, and throughout its two decades, it has been an essential platform for the development and dissemination of photographic art, both locally and internationally.

The region's most important photography fair Pinta BAphoto opens its doors October 24-27, 2024, at La Rural, Buenos Aires, Argentina. A celebration of the fair's twentieth anniversary with curatorial projects, spaces for artistic exploration, debates among experts and proposals from artists that cross photography with other disciplines.

TO SEE AND THINK THE PHOTOGRAPHIC IMAGE AT PINTA BAphoto 2024

The region's most important photography fair Pinta BAphoto opens its doors October 24-27, 2024, at La Rural, Buenos Aires, Argentina. A celebration of the fair's twentieth anniversary with curatorial projects, spaces for artistic exploration, debates among experts and proposals from artists that cross photography with other disciplines.

Cecilia Lenardón's Special Project at Pinta BAphoto, curated by Irene Gelfman, presents an installation that pushes the representation of the body through photography to the limit, transforming the static image into a living and performative experience. Entitled Cuatro piezas clave (Four Key Pieces), the work invites us to reflect on the body's boundaries and its capacity to tolerate effort and repetition.

REPETITION AND TRANSFORMATION - SPECIAL PROJECT AT PINTA BAphoto

Cecilia Lenardón's Special Project at Pinta BAphoto, curated by Irene Gelfman, presents an installation that pushes the representation of the body through photography to the limit, transforming the static image into a living and performative experience. Entitled Cuatro piezas clave (Four Key Pieces), the work invites us to reflect on the body's boundaries and its capacity to tolerate effort and repetition.

Lorenzo González Baltazar will be part of the NEXT | Out of Focus section with Primor Gallery, in the 20th edition of Pinta BAphoto. He presents his project Sapucay Marica, with photographs that capture the coexistence of the rural and the queer, performance and tradition, the intimate and the collective.

SAPUCAY MARICA: INTERVIEW WITH LORENZO GONZÁLEZ BALTAZAR

Lorenzo González Baltazar will be part of the NEXT | Out of Focus section with Primor Gallery, in the 20th edition of Pinta BAphoto. He presents his project Sapucay Marica, with photographs that capture the coexistence of the rural and the queer, performance and tradition, the intimate and the collective.

The eighth edition of Video Project, curated by Irene Gelfman, invites us to immerse in the concept of territory through the moving image. In video art we find a sense of curiosity and exploration that challenges our ideas of materiality and expands to embrace the most intimate. In six selected works, the notion of territory addresses bodies, landscapes and symbols, questioning the stability of physical and conceptual limits. The territory becomes a fluctuating space, as critical as the viewer's place.

WITNESSES OF AN EXTENDING TERRITORY - VIDEO PROJECT AT PINTA BAphoto

The eighth edition of Video Project, curated by Irene Gelfman, invites us to immerse in the concept of territory through the moving image. In video art we find a sense of curiosity and exploration that challenges our ideas of materiality and expands to embrace the most intimate. In six selected works, the notion of territory addresses bodies, landscapes and symbols, questioning the stability of physical and conceptual limits. The territory becomes a fluctuating space, as critical as the viewer's place.

Pinta BAphoto –the most important photography fair in the region– presents as a new feature the RADAR section, curated by Sebastián Vidal Mackinson. In an interview with Arte al Día, Sebastián reflects on the diversity of approaches in photography today and its growth as a medium capable of dialoguing with other forms of artistic expression.

SEBASTIÁN VIDAL MACKINSON: “CURATORSHIP IS A PROCESS OF SENSITIVITY AND COLLECTIVE INTELLIGENCE”

Pinta BAphoto –the most important photography fair in the region– presents as a new feature the RADAR section, curated by Sebastián Vidal Mackinson. In an interview with Arte al Día, Sebastián reflects on the diversity of approaches in photography today and its growth as a medium capable of dialoguing with other forms of artistic expression.

Pinta BAphoto closed its 20th anniversary at La Rural, Buenos Aires, Argentina, after a weekend that brought together the best of photography in the region and was a meeting point for gallery owners, artists, curators, collectors and photography lovers. The fair attracted more than 14,000 visitors during its three days open to the public.

PINTA BAphoto - THE EXPRESSION OF A REGION'S PHOTOGRAPHY

Pinta BAphoto closed its 20th anniversary at La Rural, Buenos Aires, Argentina, after a weekend that brought together the best of photography in the region and was a meeting point for gallery owners, artists, curators, collectors and photography lovers. The fair attracted more than 14,000 visitors during its three days open to the public.

On Saturday, November 9, 2024, a new edition of Gallery arrives to explore the neighborhoods of San Telmo and La Boca, in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Gallery promotes free tours through art circuits where visitors can discover a great diversity of galleries, museums, artists' studios and foundations. A great opportunity to bring contemporary art closer to the general public and promote the extraordinary local offer.

THE LAST GALLERY EDITION OF THE YEAR IN BUENOS AIRES

On Saturday, November 9, 2024, a new edition of Gallery arrives to explore the neighborhoods of San Telmo and La Boca, in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Gallery promotes free tours through art circuits where visitors can discover a great diversity of galleries, museums, artists' studios and foundations. A great opportunity to bring contemporary art closer to the general public and promote the extraordinary local offer.

Nebulosa de la calabaza is the title of the first solo exhibition presented in Spain by Tabita Rezaire (Paris, France, 1989), an artist living in French Guiana. Renowned for her use of new media and multidisciplinarity to explore the relationship between contemporary worlds transited from technology and their relationship with the most ancestral and spiritual environment, the Guyanese-heritage artist focuses her production on activism from the perspective of denunciation from feminism and decolonization as key points.

DENOUNCEMENT AND ORIGIN IN TABITA REZAIRE

Nebulosa de la calabaza is the title of the first solo exhibition presented in Spain by Tabita Rezaire (Paris, France, 1989), an artist living in French Guiana. Renowned for her use of new media and multidisciplinarity to explore the relationship between contemporary worlds transited from technology and their relationship with the most ancestral and spiritual environment, the Guyanese-heritage artist focuses her production on activism from the perspective of denunciation from feminism and decolonization as key points.

The Museum of Pontevedra exhibits Vento (wind, in Galician), the proposal that the artist Alberto Baraya (Bogota, Colombia, 1968) has developed and now shows at its headquarters in the Castelao Building as part of the cycle of exhibitions Infiltracións. This program aims to carry out specific projects that have as their backbone the dialogue arising from research and work with pieces from the collection of the Galician institution to promote re-readings on it.

VENTO BY ALBERTO BARAYA – IN PONTEVEDRA

The Museum of Pontevedra exhibits Vento (wind, in Galician), the proposal that the artist Alberto Baraya (Bogota, Colombia, 1968) has developed and now shows at its headquarters in the Castelao Building as part of the cycle of exhibitions Infiltracións. This program aims to carry out specific projects that have as their backbone the dialogue arising from research and work with pieces from the collection of the Galician institution to promote re-readings on it.

Based on the biologicist theories on territoriality and the relationships derived from living beings with their immediate environment, the Angeles Baños gallery from Badajoz proposes an exhibition project to three Latin American artists so that, through their experiences and their personal vision, they can materialize and express those feelings of territoriality, and always from the parallelism of the human being with the rest of living beings.

THE TERRITORIAL BY THREE LATIN AMERICAN ARTISTS AT ÁNGELES BAÑOS

Based on the biologicist theories on territoriality and the relationships derived from living beings with their immediate environment, the Angeles Baños gallery from Badajoz proposes an exhibition project to three Latin American artists so that, through their experiences and their personal vision, they can materialize and express those feelings of territoriality, and always from the parallelism of the human being with the rest of living beings.

The Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires presents two exhibitions: the first show in Argentina by US artist Onome Ekeh Especulaciones (Speculations); and El ritmo es el mejor orden (Rhythm is the best order), which brings together a group of recent drawings by Argentine artist Sofía Bohtlingk.

DOUBLE OPENING AT THE MUSEO DE ARTE MODERNO: ONOME EKEH AND SOFÍA BOHTLINGK

The Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires presents two exhibitions: the first show in Argentina by US artist Onome Ekeh Especulaciones (Speculations); and El ritmo es el mejor orden (Rhythm is the best order), which brings together a group of recent drawings by Argentine artist Sofía Bohtlingk.

The Tribute Artist section of Pinta BAphoto celebrates a decade exhibiting the trajectory of photographers who had an active participation in the field, seeking to recover and value their figure. This edition, curator Francisco Medail presents Jaime Bolotinsky, a Russian-born photographer based in Buenos Aires who was a pioneer when it came to composing his portraits, using everyday elements and a precise handling of light.

JAIME BOLOTINKSY'S EVERYDAY ELEMENTS - TRIBUTE ARTIST AT PINTA BAphoto 2024

The Tribute Artist section of Pinta BAphoto celebrates a decade exhibiting the trajectory of photographers who had an active participation in the field, seeking to recover and value their figure. This edition, curator Francisco Medail presents Jaime Bolotinsky, a Russian-born photographer based in Buenos Aires who was a pioneer when it came to composing his portraits, using everyday elements and a precise handling of light.

Pinta BAphoto celebrates its twentieth edition at La Rural, consolidating itself as one of the most important fairs dedicated to photography in Latin America. This annual event brings together galleries, artists and collectors, and throughout its two decades, it has been an essential platform for the development and dissemination of photographic art, both locally and internationally.

VISUAL CONFLUENCES - NEXT | Out of Focus AT PINTA BAphoto

Pinta BAphoto celebrates its twentieth edition at La Rural, consolidating itself as one of the most important fairs dedicated to photography in Latin America. This annual event brings together galleries, artists and collectors, and throughout its two decades, it has been an essential platform for the development and dissemination of photographic art, both locally and internationally.

The region's most important photography fair Pinta BAphoto opens its doors October 24-27, 2024, at La Rural, Buenos Aires, Argentina. A celebration of the fair's twentieth anniversary with curatorial projects, spaces for artistic exploration, debates among experts and proposals from artists that cross photography with other disciplines.

TO SEE AND THINK THE PHOTOGRAPHIC IMAGE AT PINTA BAphoto 2024

The region's most important photography fair Pinta BAphoto opens its doors October 24-27, 2024, at La Rural, Buenos Aires, Argentina. A celebration of the fair's twentieth anniversary with curatorial projects, spaces for artistic exploration, debates among experts and proposals from artists that cross photography with other disciplines.

Cecilia Lenardón's Special Project at Pinta BAphoto, curated by Irene Gelfman, presents an installation that pushes the representation of the body through photography to the limit, transforming the static image into a living and performative experience. Entitled Cuatro piezas clave (Four Key Pieces), the work invites us to reflect on the body's boundaries and its capacity to tolerate effort and repetition.

REPETITION AND TRANSFORMATION - SPECIAL PROJECT AT PINTA BAphoto

Cecilia Lenardón's Special Project at Pinta BAphoto, curated by Irene Gelfman, presents an installation that pushes the representation of the body through photography to the limit, transforming the static image into a living and performative experience. Entitled Cuatro piezas clave (Four Key Pieces), the work invites us to reflect on the body's boundaries and its capacity to tolerate effort and repetition.

Lorenzo González Baltazar will be part of the NEXT | Out of Focus section with Primor Gallery, in the 20th edition of Pinta BAphoto. He presents his project Sapucay Marica, with photographs that capture the coexistence of the rural and the queer, performance and tradition, the intimate and the collective.

SAPUCAY MARICA: INTERVIEW WITH LORENZO GONZÁLEZ BALTAZAR

Lorenzo González Baltazar will be part of the NEXT | Out of Focus section with Primor Gallery, in the 20th edition of Pinta BAphoto. He presents his project Sapucay Marica, with photographs that capture the coexistence of the rural and the queer, performance and tradition, the intimate and the collective.

The eighth edition of Video Project, curated by Irene Gelfman, invites us to immerse in the concept of territory through the moving image. In video art we find a sense of curiosity and exploration that challenges our ideas of materiality and expands to embrace the most intimate. In six selected works, the notion of territory addresses bodies, landscapes and symbols, questioning the stability of physical and conceptual limits. The territory becomes a fluctuating space, as critical as the viewer's place.

WITNESSES OF AN EXTENDING TERRITORY - VIDEO PROJECT AT PINTA BAphoto

The eighth edition of Video Project, curated by Irene Gelfman, invites us to immerse in the concept of territory through the moving image. In video art we find a sense of curiosity and exploration that challenges our ideas of materiality and expands to embrace the most intimate. In six selected works, the notion of territory addresses bodies, landscapes and symbols, questioning the stability of physical and conceptual limits. The territory becomes a fluctuating space, as critical as the viewer's place.

Pinta BAphoto –the most important photography fair in the region– presents as a new feature the RADAR section, curated by Sebastián Vidal Mackinson. In an interview with Arte al Día, Sebastián reflects on the diversity of approaches in photography today and its growth as a medium capable of dialoguing with other forms of artistic expression.

SEBASTIÁN VIDAL MACKINSON: “CURATORSHIP IS A PROCESS OF SENSITIVITY AND COLLECTIVE INTELLIGENCE”

Pinta BAphoto –the most important photography fair in the region– presents as a new feature the RADAR section, curated by Sebastián Vidal Mackinson. In an interview with Arte al Día, Sebastián reflects on the diversity of approaches in photography today and its growth as a medium capable of dialoguing with other forms of artistic expression.

Pinta BAphoto closed its 20th anniversary at La Rural, Buenos Aires, Argentina, after a weekend that brought together the best of photography in the region and was a meeting point for gallery owners, artists, curators, collectors and photography lovers. The fair attracted more than 14,000 visitors during its three days open to the public.

PINTA BAphoto - THE EXPRESSION OF A REGION'S PHOTOGRAPHY

Pinta BAphoto closed its 20th anniversary at La Rural, Buenos Aires, Argentina, after a weekend that brought together the best of photography in the region and was a meeting point for gallery owners, artists, curators, collectors and photography lovers. The fair attracted more than 14,000 visitors during its three days open to the public.

On Saturday, November 9, 2024, a new edition of Gallery arrives to explore the neighborhoods of San Telmo and La Boca, in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Gallery promotes free tours through art circuits where visitors can discover a great diversity of galleries, museums, artists' studios and foundations. A great opportunity to bring contemporary art closer to the general public and promote the extraordinary local offer.

THE LAST GALLERY EDITION OF THE YEAR IN BUENOS AIRES

On Saturday, November 9, 2024, a new edition of Gallery arrives to explore the neighborhoods of San Telmo and La Boca, in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Gallery promotes free tours through art circuits where visitors can discover a great diversity of galleries, museums, artists' studios and foundations. A great opportunity to bring contemporary art closer to the general public and promote the extraordinary local offer.

Nebulosa de la calabaza is the title of the first solo exhibition presented in Spain by Tabita Rezaire (Paris, France, 1989), an artist living in French Guiana. Renowned for her use of new media and multidisciplinarity to explore the relationship between contemporary worlds transited from technology and their relationship with the most ancestral and spiritual environment, the Guyanese-heritage artist focuses her production on activism from the perspective of denunciation from feminism and decolonization as key points.

DENOUNCEMENT AND ORIGIN IN TABITA REZAIRE

Nebulosa de la calabaza is the title of the first solo exhibition presented in Spain by Tabita Rezaire (Paris, France, 1989), an artist living in French Guiana. Renowned for her use of new media and multidisciplinarity to explore the relationship between contemporary worlds transited from technology and their relationship with the most ancestral and spiritual environment, the Guyanese-heritage artist focuses her production on activism from the perspective of denunciation from feminism and decolonization as key points.

The Museum of Pontevedra exhibits Vento (wind, in Galician), the proposal that the artist Alberto Baraya (Bogota, Colombia, 1968) has developed and now shows at its headquarters in the Castelao Building as part of the cycle of exhibitions Infiltracións. This program aims to carry out specific projects that have as their backbone the dialogue arising from research and work with pieces from the collection of the Galician institution to promote re-readings on it.

VENTO BY ALBERTO BARAYA – IN PONTEVEDRA

The Museum of Pontevedra exhibits Vento (wind, in Galician), the proposal that the artist Alberto Baraya (Bogota, Colombia, 1968) has developed and now shows at its headquarters in the Castelao Building as part of the cycle of exhibitions Infiltracións. This program aims to carry out specific projects that have as their backbone the dialogue arising from research and work with pieces from the collection of the Galician institution to promote re-readings on it.

Based on the biologicist theories on territoriality and the relationships derived from living beings with their immediate environment, the Angeles Baños gallery from Badajoz proposes an exhibition project to three Latin American artists so that, through their experiences and their personal vision, they can materialize and express those feelings of territoriality, and always from the parallelism of the human being with the rest of living beings.

THE TERRITORIAL BY THREE LATIN AMERICAN ARTISTS AT ÁNGELES BAÑOS

Based on the biologicist theories on territoriality and the relationships derived from living beings with their immediate environment, the Angeles Baños gallery from Badajoz proposes an exhibition project to three Latin American artists so that, through their experiences and their personal vision, they can materialize and express those feelings of territoriality, and always from the parallelism of the human being with the rest of living beings.

The Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires presents two exhibitions: the first show in Argentina by US artist Onome Ekeh Especulaciones (Speculations); and El ritmo es el mejor orden (Rhythm is the best order), which brings together a group of recent drawings by Argentine artist Sofía Bohtlingk.

DOUBLE OPENING AT THE MUSEO DE ARTE MODERNO: ONOME EKEH AND SOFÍA BOHTLINGK

The Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires presents two exhibitions: the first show in Argentina by US artist Onome Ekeh Especulaciones (Speculations); and El ritmo es el mejor orden (Rhythm is the best order), which brings together a group of recent drawings by Argentine artist Sofía Bohtlingk.

The Tribute Artist section of Pinta BAphoto celebrates a decade exhibiting the trajectory of photographers who had an active participation in the field, seeking to recover and value their figure. This edition, curator Francisco Medail presents Jaime Bolotinsky, a Russian-born photographer based in Buenos Aires who was a pioneer when it came to composing his portraits, using everyday elements and a precise handling of light.

JAIME BOLOTINKSY'S EVERYDAY ELEMENTS - TRIBUTE ARTIST AT PINTA BAphoto 2024

The Tribute Artist section of Pinta BAphoto celebrates a decade exhibiting the trajectory of photographers who had an active participation in the field, seeking to recover and value their figure. This edition, curator Francisco Medail presents Jaime Bolotinsky, a Russian-born photographer based in Buenos Aires who was a pioneer when it came to composing his portraits, using everyday elements and a precise handling of light.

Pinta BAphoto celebrates its twentieth edition at La Rural, consolidating itself as one of the most important fairs dedicated to photography in Latin America. This annual event brings together galleries, artists and collectors, and throughout its two decades, it has been an essential platform for the development and dissemination of photographic art, both locally and internationally.

VISUAL CONFLUENCES - NEXT | Out of Focus AT PINTA BAphoto

Pinta BAphoto celebrates its twentieth edition at La Rural, consolidating itself as one of the most important fairs dedicated to photography in Latin America. This annual event brings together galleries, artists and collectors, and throughout its two decades, it has been an essential platform for the development and dissemination of photographic art, both locally and internationally.

The region's most important photography fair Pinta BAphoto opens its doors October 24-27, 2024, at La Rural, Buenos Aires, Argentina. A celebration of the fair's twentieth anniversary with curatorial projects, spaces for artistic exploration, debates among experts and proposals from artists that cross photography with other disciplines.

TO SEE AND THINK THE PHOTOGRAPHIC IMAGE AT PINTA BAphoto 2024

The region's most important photography fair Pinta BAphoto opens its doors October 24-27, 2024, at La Rural, Buenos Aires, Argentina. A celebration of the fair's twentieth anniversary with curatorial projects, spaces for artistic exploration, debates among experts and proposals from artists that cross photography with other disciplines.

Cecilia Lenardón's Special Project at Pinta BAphoto, curated by Irene Gelfman, presents an installation that pushes the representation of the body through photography to the limit, transforming the static image into a living and performative experience. Entitled Cuatro piezas clave (Four Key Pieces), the work invites us to reflect on the body's boundaries and its capacity to tolerate effort and repetition.

REPETITION AND TRANSFORMATION - SPECIAL PROJECT AT PINTA BAphoto

Cecilia Lenardón's Special Project at Pinta BAphoto, curated by Irene Gelfman, presents an installation that pushes the representation of the body through photography to the limit, transforming the static image into a living and performative experience. Entitled Cuatro piezas clave (Four Key Pieces), the work invites us to reflect on the body's boundaries and its capacity to tolerate effort and repetition.

Lorenzo González Baltazar will be part of the NEXT | Out of Focus section with Primor Gallery, in the 20th edition of Pinta BAphoto. He presents his project Sapucay Marica, with photographs that capture the coexistence of the rural and the queer, performance and tradition, the intimate and the collective.

SAPUCAY MARICA: INTERVIEW WITH LORENZO GONZÁLEZ BALTAZAR

Lorenzo González Baltazar will be part of the NEXT | Out of Focus section with Primor Gallery, in the 20th edition of Pinta BAphoto. He presents his project Sapucay Marica, with photographs that capture the coexistence of the rural and the queer, performance and tradition, the intimate and the collective.

The eighth edition of Video Project, curated by Irene Gelfman, invites us to immerse in the concept of territory through the moving image. In video art we find a sense of curiosity and exploration that challenges our ideas of materiality and expands to embrace the most intimate. In six selected works, the notion of territory addresses bodies, landscapes and symbols, questioning the stability of physical and conceptual limits. The territory becomes a fluctuating space, as critical as the viewer's place.

WITNESSES OF AN EXTENDING TERRITORY - VIDEO PROJECT AT PINTA BAphoto

The eighth edition of Video Project, curated by Irene Gelfman, invites us to immerse in the concept of territory through the moving image. In video art we find a sense of curiosity and exploration that challenges our ideas of materiality and expands to embrace the most intimate. In six selected works, the notion of territory addresses bodies, landscapes and symbols, questioning the stability of physical and conceptual limits. The territory becomes a fluctuating space, as critical as the viewer's place.

Pinta BAphoto –the most important photography fair in the region– presents as a new feature the RADAR section, curated by Sebastián Vidal Mackinson. In an interview with Arte al Día, Sebastián reflects on the diversity of approaches in photography today and its growth as a medium capable of dialoguing with other forms of artistic expression.

SEBASTIÁN VIDAL MACKINSON: “CURATORSHIP IS A PROCESS OF SENSITIVITY AND COLLECTIVE INTELLIGENCE”

Pinta BAphoto –the most important photography fair in the region– presents as a new feature the RADAR section, curated by Sebastián Vidal Mackinson. In an interview with Arte al Día, Sebastián reflects on the diversity of approaches in photography today and its growth as a medium capable of dialoguing with other forms of artistic expression.

Pinta BAphoto closed its 20th anniversary at La Rural, Buenos Aires, Argentina, after a weekend that brought together the best of photography in the region and was a meeting point for gallery owners, artists, curators, collectors and photography lovers. The fair attracted more than 14,000 visitors during its three days open to the public.

PINTA BAphoto - THE EXPRESSION OF A REGION'S PHOTOGRAPHY

Pinta BAphoto closed its 20th anniversary at La Rural, Buenos Aires, Argentina, after a weekend that brought together the best of photography in the region and was a meeting point for gallery owners, artists, curators, collectors and photography lovers. The fair attracted more than 14,000 visitors during its three days open to the public.

On Saturday, November 9, 2024, a new edition of Gallery arrives to explore the neighborhoods of San Telmo and La Boca, in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Gallery promotes free tours through art circuits where visitors can discover a great diversity of galleries, museums, artists' studios and foundations. A great opportunity to bring contemporary art closer to the general public and promote the extraordinary local offer.

THE LAST GALLERY EDITION OF THE YEAR IN BUENOS AIRES

On Saturday, November 9, 2024, a new edition of Gallery arrives to explore the neighborhoods of San Telmo and La Boca, in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Gallery promotes free tours through art circuits where visitors can discover a great diversity of galleries, museums, artists' studios and foundations. A great opportunity to bring contemporary art closer to the general public and promote the extraordinary local offer.

Nebulosa de la calabaza is the title of the first solo exhibition presented in Spain by Tabita Rezaire (Paris, France, 1989), an artist living in French Guiana. Renowned for her use of new media and multidisciplinarity to explore the relationship between contemporary worlds transited from technology and their relationship with the most ancestral and spiritual environment, the Guyanese-heritage artist focuses her production on activism from the perspective of denunciation from feminism and decolonization as key points.

DENOUNCEMENT AND ORIGIN IN TABITA REZAIRE

Nebulosa de la calabaza is the title of the first solo exhibition presented in Spain by Tabita Rezaire (Paris, France, 1989), an artist living in French Guiana. Renowned for her use of new media and multidisciplinarity to explore the relationship between contemporary worlds transited from technology and their relationship with the most ancestral and spiritual environment, the Guyanese-heritage artist focuses her production on activism from the perspective of denunciation from feminism and decolonization as key points.

The Museum of Pontevedra exhibits Vento (wind, in Galician), the proposal that the artist Alberto Baraya (Bogota, Colombia, 1968) has developed and now shows at its headquarters in the Castelao Building as part of the cycle of exhibitions Infiltracións. This program aims to carry out specific projects that have as their backbone the dialogue arising from research and work with pieces from the collection of the Galician institution to promote re-readings on it.

VENTO BY ALBERTO BARAYA – IN PONTEVEDRA

The Museum of Pontevedra exhibits Vento (wind, in Galician), the proposal that the artist Alberto Baraya (Bogota, Colombia, 1968) has developed and now shows at its headquarters in the Castelao Building as part of the cycle of exhibitions Infiltracións. This program aims to carry out specific projects that have as their backbone the dialogue arising from research and work with pieces from the collection of the Galician institution to promote re-readings on it.

Based on the biologicist theories on territoriality and the relationships derived from living beings with their immediate environment, the Angeles Baños gallery from Badajoz proposes an exhibition project to three Latin American artists so that, through their experiences and their personal vision, they can materialize and express those feelings of territoriality, and always from the parallelism of the human being with the rest of living beings.

THE TERRITORIAL BY THREE LATIN AMERICAN ARTISTS AT ÁNGELES BAÑOS

Based on the biologicist theories on territoriality and the relationships derived from living beings with their immediate environment, the Angeles Baños gallery from Badajoz proposes an exhibition project to three Latin American artists so that, through their experiences and their personal vision, they can materialize and express those feelings of territoriality, and always from the parallelism of the human being with the rest of living beings.

The Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires presents two exhibitions: the first show in Argentina by US artist Onome Ekeh Especulaciones (Speculations); and El ritmo es el mejor orden (Rhythm is the best order), which brings together a group of recent drawings by Argentine artist Sofía Bohtlingk.

DOUBLE OPENING AT THE MUSEO DE ARTE MODERNO: ONOME EKEH AND SOFÍA BOHTLINGK

The Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires presents two exhibitions: the first show in Argentina by US artist Onome Ekeh Especulaciones (Speculations); and El ritmo es el mejor orden (Rhythm is the best order), which brings together a group of recent drawings by Argentine artist Sofía Bohtlingk.

The Tribute Artist section of Pinta BAphoto celebrates a decade exhibiting the trajectory of photographers who had an active participation in the field, seeking to recover and value their figure. This edition, curator Francisco Medail presents Jaime Bolotinsky, a Russian-born photographer based in Buenos Aires who was a pioneer when it came to composing his portraits, using everyday elements and a precise handling of light.

JAIME BOLOTINKSY'S EVERYDAY ELEMENTS - TRIBUTE ARTIST AT PINTA BAphoto 2024

The Tribute Artist section of Pinta BAphoto celebrates a decade exhibiting the trajectory of photographers who had an active participation in the field, seeking to recover and value their figure. This edition, curator Francisco Medail presents Jaime Bolotinsky, a Russian-born photographer based in Buenos Aires who was a pioneer when it came to composing his portraits, using everyday elements and a precise handling of light.

Pinta BAphoto celebrates its twentieth edition at La Rural, consolidating itself as one of the most important fairs dedicated to photography in Latin America. This annual event brings together galleries, artists and collectors, and throughout its two decades, it has been an essential platform for the development and dissemination of photographic art, both locally and internationally.

VISUAL CONFLUENCES - NEXT | Out of Focus AT PINTA BAphoto

Pinta BAphoto celebrates its twentieth edition at La Rural, consolidating itself as one of the most important fairs dedicated to photography in Latin America. This annual event brings together galleries, artists and collectors, and throughout its two decades, it has been an essential platform for the development and dissemination of photographic art, both locally and internationally.

The region's most important photography fair Pinta BAphoto opens its doors October 24-27, 2024, at La Rural, Buenos Aires, Argentina. A celebration of the fair's twentieth anniversary with curatorial projects, spaces for artistic exploration, debates among experts and proposals from artists that cross photography with other disciplines.

TO SEE AND THINK THE PHOTOGRAPHIC IMAGE AT PINTA BAphoto 2024

The region's most important photography fair Pinta BAphoto opens its doors October 24-27, 2024, at La Rural, Buenos Aires, Argentina. A celebration of the fair's twentieth anniversary with curatorial projects, spaces for artistic exploration, debates among experts and proposals from artists that cross photography with other disciplines.

Cecilia Lenardón's Special Project at Pinta BAphoto, curated by Irene Gelfman, presents an installation that pushes the representation of the body through photography to the limit, transforming the static image into a living and performative experience. Entitled Cuatro piezas clave (Four Key Pieces), the work invites us to reflect on the body's boundaries and its capacity to tolerate effort and repetition.

REPETITION AND TRANSFORMATION - SPECIAL PROJECT AT PINTA BAphoto

Cecilia Lenardón's Special Project at Pinta BAphoto, curated by Irene Gelfman, presents an installation that pushes the representation of the body through photography to the limit, transforming the static image into a living and performative experience. Entitled Cuatro piezas clave (Four Key Pieces), the work invites us to reflect on the body's boundaries and its capacity to tolerate effort and repetition.

Lorenzo González Baltazar will be part of the NEXT | Out of Focus section with Primor Gallery, in the 20th edition of Pinta BAphoto. He presents his project Sapucay Marica, with photographs that capture the coexistence of the rural and the queer, performance and tradition, the intimate and the collective.

SAPUCAY MARICA: INTERVIEW WITH LORENZO GONZÁLEZ BALTAZAR

Lorenzo González Baltazar will be part of the NEXT | Out of Focus section with Primor Gallery, in the 20th edition of Pinta BAphoto. He presents his project Sapucay Marica, with photographs that capture the coexistence of the rural and the queer, performance and tradition, the intimate and the collective.

The eighth edition of Video Project, curated by Irene Gelfman, invites us to immerse in the concept of territory through the moving image. In video art we find a sense of curiosity and exploration that challenges our ideas of materiality and expands to embrace the most intimate. In six selected works, the notion of territory addresses bodies, landscapes and symbols, questioning the stability of physical and conceptual limits. The territory becomes a fluctuating space, as critical as the viewer's place.

WITNESSES OF AN EXTENDING TERRITORY - VIDEO PROJECT AT PINTA BAphoto

The eighth edition of Video Project, curated by Irene Gelfman, invites us to immerse in the concept of territory through the moving image. In video art we find a sense of curiosity and exploration that challenges our ideas of materiality and expands to embrace the most intimate. In six selected works, the notion of territory addresses bodies, landscapes and symbols, questioning the stability of physical and conceptual limits. The territory becomes a fluctuating space, as critical as the viewer's place.

Pinta BAphoto –the most important photography fair in the region– presents as a new feature the RADAR section, curated by Sebastián Vidal Mackinson. In an interview with Arte al Día, Sebastián reflects on the diversity of approaches in photography today and its growth as a medium capable of dialoguing with other forms of artistic expression.

SEBASTIÁN VIDAL MACKINSON: “CURATORSHIP IS A PROCESS OF SENSITIVITY AND COLLECTIVE INTELLIGENCE”

Pinta BAphoto –the most important photography fair in the region– presents as a new feature the RADAR section, curated by Sebastián Vidal Mackinson. In an interview with Arte al Día, Sebastián reflects on the diversity of approaches in photography today and its growth as a medium capable of dialoguing with other forms of artistic expression.

Pinta BAphoto closed its 20th anniversary at La Rural, Buenos Aires, Argentina, after a weekend that brought together the best of photography in the region and was a meeting point for gallery owners, artists, curators, collectors and photography lovers. The fair attracted more than 14,000 visitors during its three days open to the public.

PINTA BAphoto - THE EXPRESSION OF A REGION'S PHOTOGRAPHY

Pinta BAphoto closed its 20th anniversary at La Rural, Buenos Aires, Argentina, after a weekend that brought together the best of photography in the region and was a meeting point for gallery owners, artists, curators, collectors and photography lovers. The fair attracted more than 14,000 visitors during its three days open to the public.

On Saturday, November 9, 2024, a new edition of Gallery arrives to explore the neighborhoods of San Telmo and La Boca, in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Gallery promotes free tours through art circuits where visitors can discover a great diversity of galleries, museums, artists' studios and foundations. A great opportunity to bring contemporary art closer to the general public and promote the extraordinary local offer.

THE LAST GALLERY EDITION OF THE YEAR IN BUENOS AIRES

On Saturday, November 9, 2024, a new edition of Gallery arrives to explore the neighborhoods of San Telmo and La Boca, in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Gallery promotes free tours through art circuits where visitors can discover a great diversity of galleries, museums, artists' studios and foundations. A great opportunity to bring contemporary art closer to the general public and promote the extraordinary local offer.

Nebulosa de la calabaza is the title of the first solo exhibition presented in Spain by Tabita Rezaire (Paris, France, 1989), an artist living in French Guiana. Renowned for her use of new media and multidisciplinarity to explore the relationship between contemporary worlds transited from technology and their relationship with the most ancestral and spiritual environment, the Guyanese-heritage artist focuses her production on activism from the perspective of denunciation from feminism and decolonization as key points.

DENOUNCEMENT AND ORIGIN IN TABITA REZAIRE

Nebulosa de la calabaza is the title of the first solo exhibition presented in Spain by Tabita Rezaire (Paris, France, 1989), an artist living in French Guiana. Renowned for her use of new media and multidisciplinarity to explore the relationship between contemporary worlds transited from technology and their relationship with the most ancestral and spiritual environment, the Guyanese-heritage artist focuses her production on activism from the perspective of denunciation from feminism and decolonization as key points.

The Museum of Pontevedra exhibits Vento (wind, in Galician), the proposal that the artist Alberto Baraya (Bogota, Colombia, 1968) has developed and now shows at its headquarters in the Castelao Building as part of the cycle of exhibitions Infiltracións. This program aims to carry out specific projects that have as their backbone the dialogue arising from research and work with pieces from the collection of the Galician institution to promote re-readings on it.

VENTO BY ALBERTO BARAYA – IN PONTEVEDRA

The Museum of Pontevedra exhibits Vento (wind, in Galician), the proposal that the artist Alberto Baraya (Bogota, Colombia, 1968) has developed and now shows at its headquarters in the Castelao Building as part of the cycle of exhibitions Infiltracións. This program aims to carry out specific projects that have as their backbone the dialogue arising from research and work with pieces from the collection of the Galician institution to promote re-readings on it.

Based on the biologicist theories on territoriality and the relationships derived from living beings with their immediate environment, the Angeles Baños gallery from Badajoz proposes an exhibition project to three Latin American artists so that, through their experiences and their personal vision, they can materialize and express those feelings of territoriality, and always from the parallelism of the human being with the rest of living beings.

THE TERRITORIAL BY THREE LATIN AMERICAN ARTISTS AT ÁNGELES BAÑOS

Based on the biologicist theories on territoriality and the relationships derived from living beings with their immediate environment, the Angeles Baños gallery from Badajoz proposes an exhibition project to three Latin American artists so that, through their experiences and their personal vision, they can materialize and express those feelings of territoriality, and always from the parallelism of the human being with the rest of living beings.

The Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires presents two exhibitions: the first show in Argentina by US artist Onome Ekeh Especulaciones (Speculations); and El ritmo es el mejor orden (Rhythm is the best order), which brings together a group of recent drawings by Argentine artist Sofía Bohtlingk.

DOUBLE OPENING AT THE MUSEO DE ARTE MODERNO: ONOME EKEH AND SOFÍA BOHTLINGK

The Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires presents two exhibitions: the first show in Argentina by US artist Onome Ekeh Especulaciones (Speculations); and El ritmo es el mejor orden (Rhythm is the best order), which brings together a group of recent drawings by Argentine artist Sofía Bohtlingk.

The Tribute Artist section of Pinta BAphoto celebrates a decade exhibiting the trajectory of photographers who had an active participation in the field, seeking to recover and value their figure. This edition, curator Francisco Medail presents Jaime Bolotinsky, a Russian-born photographer based in Buenos Aires who was a pioneer when it came to composing his portraits, using everyday elements and a precise handling of light.

JAIME BOLOTINKSY'S EVERYDAY ELEMENTS - TRIBUTE ARTIST AT PINTA BAphoto 2024

The Tribute Artist section of Pinta BAphoto celebrates a decade exhibiting the trajectory of photographers who had an active participation in the field, seeking to recover and value their figure. This edition, curator Francisco Medail presents Jaime Bolotinsky, a Russian-born photographer based in Buenos Aires who was a pioneer when it came to composing his portraits, using everyday elements and a precise handling of light.

Pinta BAphoto celebrates its twentieth edition at La Rural, consolidating itself as one of the most important fairs dedicated to photography in Latin America. This annual event brings together galleries, artists and collectors, and throughout its two decades, it has been an essential platform for the development and dissemination of photographic art, both locally and internationally.

VISUAL CONFLUENCES - NEXT | Out of Focus AT PINTA BAphoto

Pinta BAphoto celebrates its twentieth edition at La Rural, consolidating itself as one of the most important fairs dedicated to photography in Latin America. This annual event brings together galleries, artists and collectors, and throughout its two decades, it has been an essential platform for the development and dissemination of photographic art, both locally and internationally.

The region's most important photography fair Pinta BAphoto opens its doors October 24-27, 2024, at La Rural, Buenos Aires, Argentina. A celebration of the fair's twentieth anniversary with curatorial projects, spaces for artistic exploration, debates among experts and proposals from artists that cross photography with other disciplines.

TO SEE AND THINK THE PHOTOGRAPHIC IMAGE AT PINTA BAphoto 2024

The region's most important photography fair Pinta BAphoto opens its doors October 24-27, 2024, at La Rural, Buenos Aires, Argentina. A celebration of the fair's twentieth anniversary with curatorial projects, spaces for artistic exploration, debates among experts and proposals from artists that cross photography with other disciplines.

Cecilia Lenardón's Special Project at Pinta BAphoto, curated by Irene Gelfman, presents an installation that pushes the representation of the body through photography to the limit, transforming the static image into a living and performative experience. Entitled Cuatro piezas clave (Four Key Pieces), the work invites us to reflect on the body's boundaries and its capacity to tolerate effort and repetition.

REPETITION AND TRANSFORMATION - SPECIAL PROJECT AT PINTA BAphoto

Cecilia Lenardón's Special Project at Pinta BAphoto, curated by Irene Gelfman, presents an installation that pushes the representation of the body through photography to the limit, transforming the static image into a living and performative experience. Entitled Cuatro piezas clave (Four Key Pieces), the work invites us to reflect on the body's boundaries and its capacity to tolerate effort and repetition.

Lorenzo González Baltazar will be part of the NEXT | Out of Focus section with Primor Gallery, in the 20th edition of Pinta BAphoto. He presents his project Sapucay Marica, with photographs that capture the coexistence of the rural and the queer, performance and tradition, the intimate and the collective.

SAPUCAY MARICA: INTERVIEW WITH LORENZO GONZÁLEZ BALTAZAR

Lorenzo González Baltazar will be part of the NEXT | Out of Focus section with Primor Gallery, in the 20th edition of Pinta BAphoto. He presents his project Sapucay Marica, with photographs that capture the coexistence of the rural and the queer, performance and tradition, the intimate and the collective.

The eighth edition of Video Project, curated by Irene Gelfman, invites us to immerse in the concept of territory through the moving image. In video art we find a sense of curiosity and exploration that challenges our ideas of materiality and expands to embrace the most intimate. In six selected works, the notion of territory addresses bodies, landscapes and symbols, questioning the stability of physical and conceptual limits. The territory becomes a fluctuating space, as critical as the viewer's place.

WITNESSES OF AN EXTENDING TERRITORY - VIDEO PROJECT AT PINTA BAphoto

The eighth edition of Video Project, curated by Irene Gelfman, invites us to immerse in the concept of territory through the moving image. In video art we find a sense of curiosity and exploration that challenges our ideas of materiality and expands to embrace the most intimate. In six selected works, the notion of territory addresses bodies, landscapes and symbols, questioning the stability of physical and conceptual limits. The territory becomes a fluctuating space, as critical as the viewer's place.

Pinta BAphoto –the most important photography fair in the region– presents as a new feature the RADAR section, curated by Sebastián Vidal Mackinson. In an interview with Arte al Día, Sebastián reflects on the diversity of approaches in photography today and its growth as a medium capable of dialoguing with other forms of artistic expression.

SEBASTIÁN VIDAL MACKINSON: “CURATORSHIP IS A PROCESS OF SENSITIVITY AND COLLECTIVE INTELLIGENCE”

Pinta BAphoto –the most important photography fair in the region– presents as a new feature the RADAR section, curated by Sebastián Vidal Mackinson. In an interview with Arte al Día, Sebastián reflects on the diversity of approaches in photography today and its growth as a medium capable of dialoguing with other forms of artistic expression.

Pinta BAphoto closed its 20th anniversary at La Rural, Buenos Aires, Argentina, after a weekend that brought together the best of photography in the region and was a meeting point for gallery owners, artists, curators, collectors and photography lovers. The fair attracted more than 14,000 visitors during its three days open to the public.

PINTA BAphoto - THE EXPRESSION OF A REGION'S PHOTOGRAPHY

Pinta BAphoto closed its 20th anniversary at La Rural, Buenos Aires, Argentina, after a weekend that brought together the best of photography in the region and was a meeting point for gallery owners, artists, curators, collectors and photography lovers. The fair attracted more than 14,000 visitors during its three days open to the public.

On Saturday, November 9, 2024, a new edition of Gallery arrives to explore the neighborhoods of San Telmo and La Boca, in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Gallery promotes free tours through art circuits where visitors can discover a great diversity of galleries, museums, artists' studios and foundations. A great opportunity to bring contemporary art closer to the general public and promote the extraordinary local offer.

THE LAST GALLERY EDITION OF THE YEAR IN BUENOS AIRES

On Saturday, November 9, 2024, a new edition of Gallery arrives to explore the neighborhoods of San Telmo and La Boca, in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Gallery promotes free tours through art circuits where visitors can discover a great diversity of galleries, museums, artists' studios and foundations. A great opportunity to bring contemporary art closer to the general public and promote the extraordinary local offer.

Nebulosa de la calabaza is the title of the first solo exhibition presented in Spain by Tabita Rezaire (Paris, France, 1989), an artist living in French Guiana. Renowned for her use of new media and multidisciplinarity to explore the relationship between contemporary worlds transited from technology and their relationship with the most ancestral and spiritual environment, the Guyanese-heritage artist focuses her production on activism from the perspective of denunciation from feminism and decolonization as key points.

DENOUNCEMENT AND ORIGIN IN TABITA REZAIRE

Nebulosa de la calabaza is the title of the first solo exhibition presented in Spain by Tabita Rezaire (Paris, France, 1989), an artist living in French Guiana. Renowned for her use of new media and multidisciplinarity to explore the relationship between contemporary worlds transited from technology and their relationship with the most ancestral and spiritual environment, the Guyanese-heritage artist focuses her production on activism from the perspective of denunciation from feminism and decolonization as key points.

The Museum of Pontevedra exhibits Vento (wind, in Galician), the proposal that the artist Alberto Baraya (Bogota, Colombia, 1968) has developed and now shows at its headquarters in the Castelao Building as part of the cycle of exhibitions Infiltracións. This program aims to carry out specific projects that have as their backbone the dialogue arising from research and work with pieces from the collection of the Galician institution to promote re-readings on it.

VENTO BY ALBERTO BARAYA – IN PONTEVEDRA

The Museum of Pontevedra exhibits Vento (wind, in Galician), the proposal that the artist Alberto Baraya (Bogota, Colombia, 1968) has developed and now shows at its headquarters in the Castelao Building as part of the cycle of exhibitions Infiltracións. This program aims to carry out specific projects that have as their backbone the dialogue arising from research and work with pieces from the collection of the Galician institution to promote re-readings on it.

Based on the biologicist theories on territoriality and the relationships derived from living beings with their immediate environment, the Angeles Baños gallery from Badajoz proposes an exhibition project to three Latin American artists so that, through their experiences and their personal vision, they can materialize and express those feelings of territoriality, and always from the parallelism of the human being with the rest of living beings.

THE TERRITORIAL BY THREE LATIN AMERICAN ARTISTS AT ÁNGELES BAÑOS

Based on the biologicist theories on territoriality and the relationships derived from living beings with their immediate environment, the Angeles Baños gallery from Badajoz proposes an exhibition project to three Latin American artists so that, through their experiences and their personal vision, they can materialize and express those feelings of territoriality, and always from the parallelism of the human being with the rest of living beings.

The Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires presents two exhibitions: the first show in Argentina by US artist Onome Ekeh Especulaciones (Speculations); and El ritmo es el mejor orden (Rhythm is the best order), which brings together a group of recent drawings by Argentine artist Sofía Bohtlingk.

DOUBLE OPENING AT THE MUSEO DE ARTE MODERNO: ONOME EKEH AND SOFÍA BOHTLINGK

The Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires presents two exhibitions: the first show in Argentina by US artist Onome Ekeh Especulaciones (Speculations); and El ritmo es el mejor orden (Rhythm is the best order), which brings together a group of recent drawings by Argentine artist Sofía Bohtlingk.