GIULIANA VIDARTE: "THROUGH EXHIBITIONS WE CAN LOOK AT THE PAST IN ORDER TO THINK ABOUT TODAY"

Giuliana Vidarte is a curator, art historian and teacher. Her work focuses on the rewriting of history from the perspective of the discourse of the Peruvian Amazon. In an interview with Arte al Día, she talks about her career and how she developed the curatorial proposal for the NEXT section for Pinta Miami 2023.

What motivated you to focus on the relationship between visual arts and literature, especially in the context of the Peruvian Amazon?

My research and curatorial work initially focused on art and archival projects by contemporary artists who propose alternative discourses and an urgent rewriting of historical narratives, offering reinterpretations of the imaginary of Ancient Peru. Subsequently, I developed several research projects on artistic practices linked to the context of the Amazon. These exhibitions brought together artistic projects that proposed to rewrite the official narratives of Amazonian history, highlighting the need for a renewal of the discourses linked to the boom of rubber extraction. Other projects delved into the complex relationships between animals, plants and humans, or the concepts of nature and culture, in the Amazon, which are condensed into mythical narratives. Including the work of artists who create representations of these myths and establish relationships of dialogue with other spaces of knowledge, enabling the updating of this mythology and promoting its dissemination and discussion.

Thanks to the generosity of dear friends and colleagues, I arrived in the context of the Amazon and found a space where I could contribute to the development of lines of research on the history of Amazonian art and where I could accompany creative processes designed to make visible the urgent problems of this region.

-

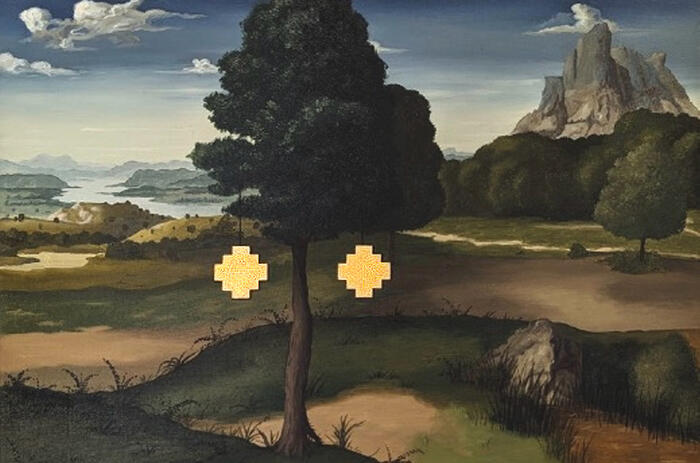

Víctor Churay, ‘Mapa de cielo bora’ (siglo XX), pintura sobre llanchama. Colección Macera-Carnero en custodia del Museo Central. Banco Central de Reserva del Perú. Parte de la exposición LOS RÍOS PUEDEN EXISTIR SIN AGUAS PERO NO SIN ORILLAS, curada por Giuliana Vidarte y Christian Bendayán.

-

Víctor Churay, ‘Mapa de cielo bora’ (siglo XX), pintura sobre llanchama. Colección Macera-Carnero en custodia del Museo Central. Banco Central de Reserva del Perú. Parte de la exposición LOS RÍOS PUEDEN EXISTIR SIN AGUAS PERO NO SIN ORILLAS, curada por Giuliana Vidarte y Christian Bendayán.

Tell us about your participation as curatorial assistant in the Peruvian Pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennale. What lessons did you learn from this international experience?

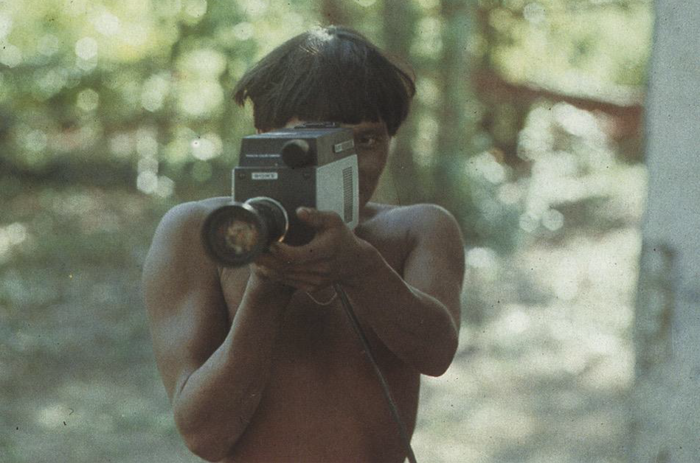

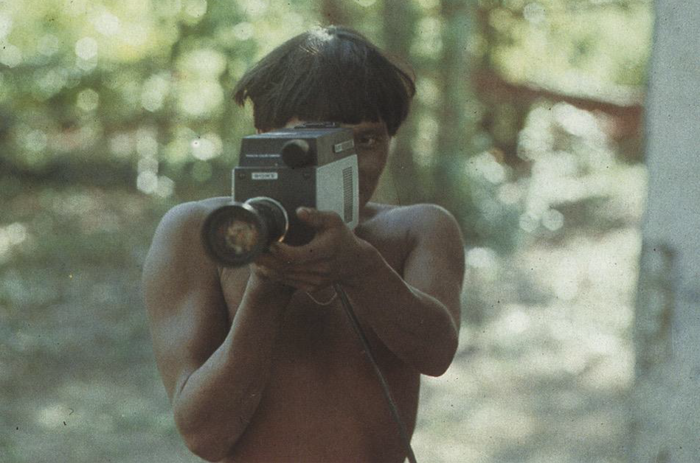

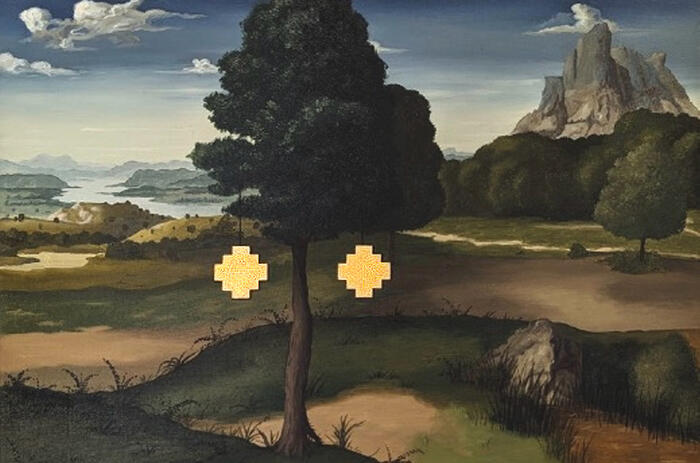

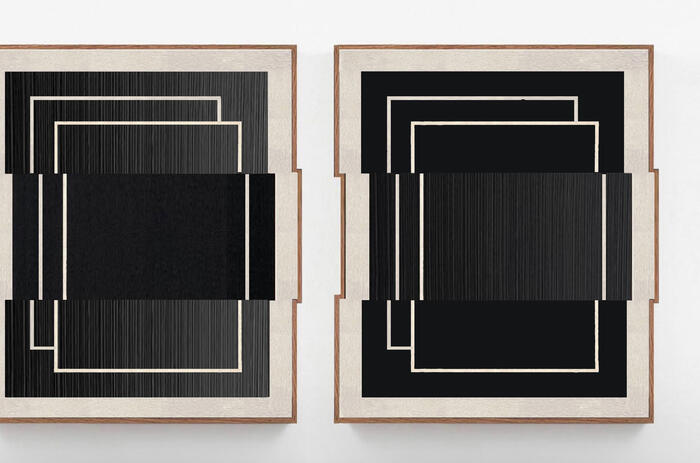

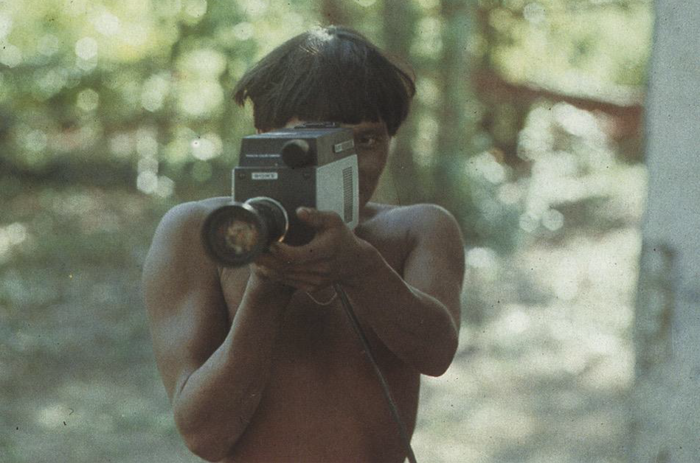

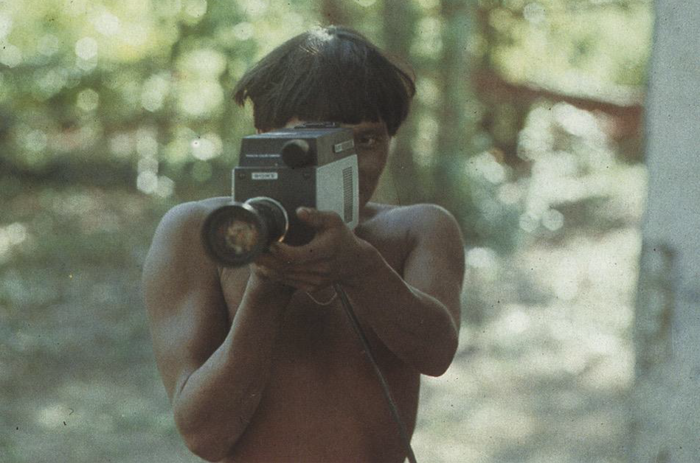

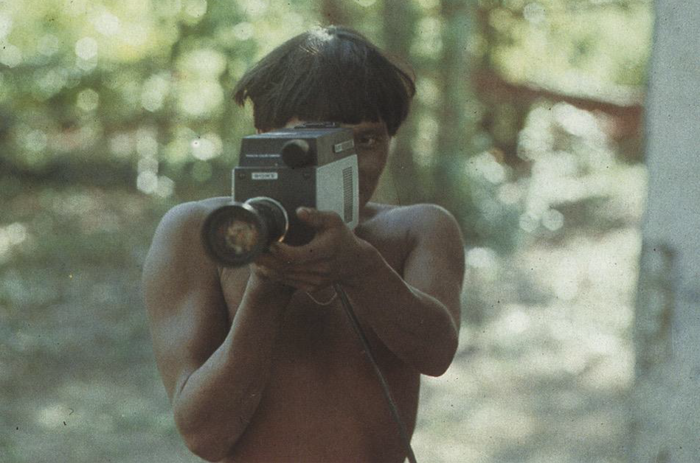

In 2019, I was part of the curatorial team of the Peruvian Pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennale as curatorial assistant. "Anthropophagous Indians" A Butterfly Garden in the Jungle (urban), curated by Gustavo Buntinx, included the work of Peruvian artists Christian Bendayán and Segundo Candiño, along with historical material by German entomologist Otto Michael and Spanish photographer Manuel Rodríguez Lira. This experience allowed me to problematize the role of contemporary artistic practices in relation to the creation of national historical imaginaries, collective memories, identity and histories from a complex and convulsive context such as the Peruvian one. It was an experience of collective work that I value very much, which allowed me to think a lot about the challenges of bringing the debates of a context to a much more global space of discussion. I learned a lot about the modes of research and creation of my colleagues.

-

"Indios antropófagos" Un jardín de mariposas en la selva (urbana). Proyecto curatorial del pabellón de Perú en la Bienal de Venecia 2019.

-

"Indios antropófagos" Un jardín de mariposas en la selva (urbana). Proyecto curatorial del pabellón de Perú en la Bienal de Venecia 2019.

-

"Indios antropófagos" Un jardín de mariposas en la selva (urbana). Proyecto curatorial del pabellón de Perú en la Bienal de Venecia 2019.

As Head of Curatorship and Collection at MAC Lima, how do you define your role? Is there a particular vision that you seek to communicate in the design of the exhibitions?

In the last five years, as Head of Curatorship and Collection of the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Lima, I have been in charge of the design and execution of the Museum's curatorial program in collaboration and dialogue with the different work areas. The MAC Lima is an institution dedicated to the promotion, research and dissemination of contemporary art practices in Peru. It also houses the original collection of the Instituto de Arte Contemporáneo. The program I developed for the Museum initially focused on the practices of contemporary Peruvian artists and their dialogues with the Latin American context. Within this broad body of work, we recognized research themes that we have subsequently developed with greater attention as part of the Museum's various programs. These themes include contemporary practices that propose the reinterpretation and updating of the knowledge, mythology and technology of the Ancient Peruvian civilizations, as well as proposals that open a dialogue around the territory we inhabit, the links we establish with it, the debate on concepts such as nature or sustainability, and the discussion of current issues in the Peruvian and global context, such as pollution, deforestation and the environmental crisis.

-

Antonio Seguí, Me estoy yendo (1989) [detalle], litografía sobre papel. Parte de la exposición HISTORIAS DE PAPEL 1. Cuerpo, mito e historia en la colección sobre papel del MAC Lima, curada por Giuliana Vidarte.

-

Antonio Seguí, Me estoy yendo (1989) [detalle], litografía sobre papel. Parte de la exposición HISTORIAS DE PAPEL 1. Cuerpo, mito e historia en la colección sobre papel del MAC Lima, curada por Giuliana Vidarte.

-

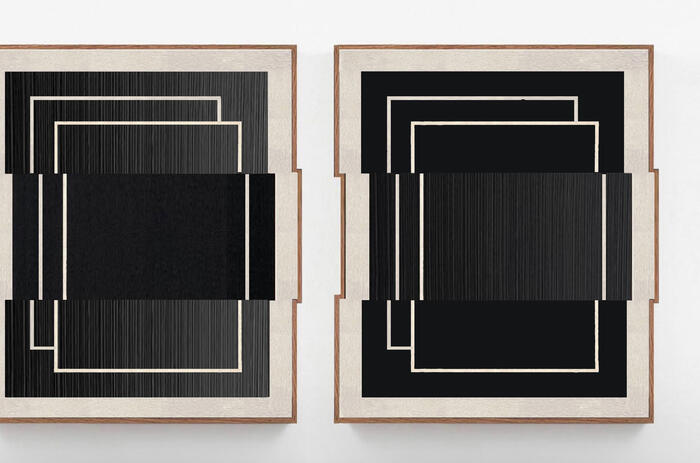

Retorno Solar de Luis Enrique Zela-Koort. Premio MAC Lima Arte e Innovación 2022. Curado por Giuliana Vidarte.

Pinta Miami 2023: What were your expectations this year for the curatorship of the NEXT section? What do you feel was achieved with the selection of projects?

The whole work process for this year's NEXT section has been very enriching for me because it is an invitation to think about the relationships between proposals in a very diverse environment, but in which it is possible to recognize shared problems in order to establish reflections on the conditions of the present and possible new configurations of scenarios for the future. I have been able to establish closer contacts with practices that interested me a lot in Lima, Buenos Aires, Guayaquil, Córdoba, Rosario, Valparaiso and Bogotá. It also seems to me that the challenge of collaboration between galleries and proposals, which is the basis of the section, contributes to the development of conversations and exchanges that open new paths to think about local contexts and artists' works and that I hope will foster the emergence of other collaborative proposals.

Pinta Miami 2023: What brings together the 10 galleries in this specific edition? What do they express?

I think it's possible to highlight how the projects that are part of this year's NEXT section affirm their role in each of their contexts as spaces for encounters, experimentation and training, and that seek to contribute to the decentralization of artistic practices. These are galleries that emerge to respond to the local reality and that accompany creative projects to analyze the interrelations between different vital environments and the contradictions and conflicts of contemporary societies. They are also proposals that broaden the definitions of emerging artistic practices and extend lines of dialogue between different generations, means of creation and geographic spaces.

-

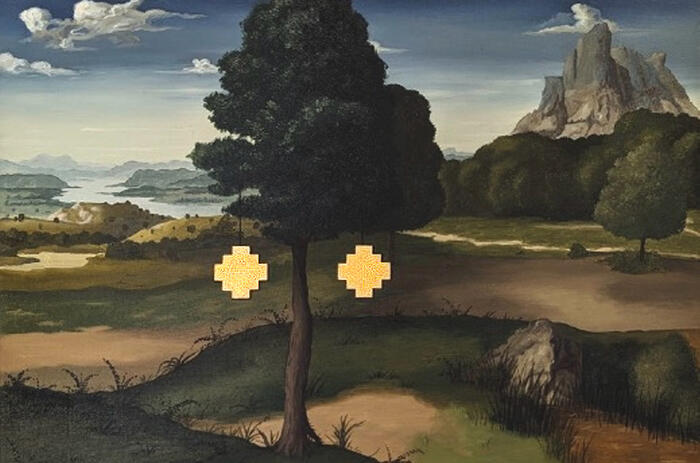

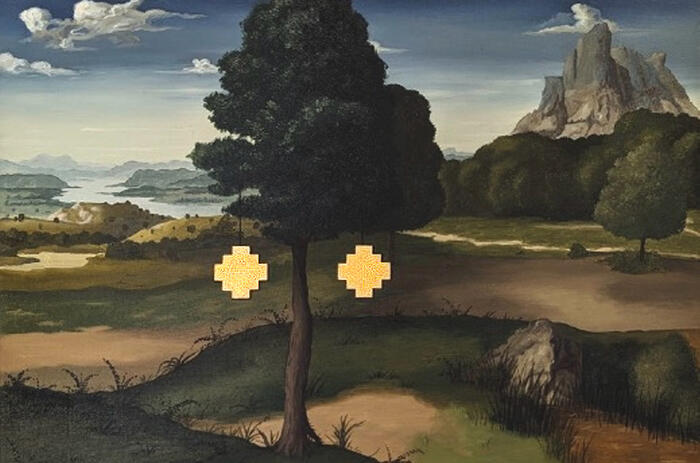

Alicia Nakatsuka, Sin título, Impenetrable, 2021, 190x115, óleo sobre tela

-

Alicia Nakatsuka, Sin título, Impenetrable, 2021, 190x115, óleo sobre tela

-

Crudo, Egar Murillo, Atardecer en la red social (2002). Tinta sobre wallpaper. 85x88cm

-

Ivet Salazar. 25 gotas. 2023. 7x5x5. Anillado Paracas en cerámica - BLOC Art.

What value do you think there is in "the emergent"? Are there specific themes that you consider important to address in this context of Latin American contemporary art?

It is a term that can be read from different perspectives and I think that galleries affirm it in different ways as well. On the one hand, there is a focus on how this definition of "emergent" is understood, linked to the trajectory of the creators. My intention for the section has been to open up the various dimensions in which a term like this is thought from the work of the galleries and understood in each local context. At the same time, it was important to bring together practices that account for debates that are urgent for Latin American contemporary art today, such as reflections on the processes of colonization, the devastation of ecosystems, the excessive extraction of resources and the ways of inhabiting and experiencing the world from the means of contemporary visuality and virtuality. The section also includes proposals that evoke new configurations for future scenarios based on the representation of ancestral schemes, family memories and everyday narratives.

What are the biggest challenges you face as a curator in the contemporary art scene? And the opportunities you see for the future?

From my practice I think it is always important to think about how our work is relevant to the working and creative environments to which we belong. It is important to integrate our research and exhibition projects into the dialogues and discussions that are urgent for the contexts we are part of. From the curatorial work, it is currently possible to accompany artistic projects that propose to rethink historical discourses, recover traditional knowledge, make visible the artistic practices of different communities and recognize the space to which each creator belongs, their particularities and the fundamental link with the context. Today we reflect on history and memory in order to understand ourselves and recover broad and diverse discourses for our communities. From the exhibitions we can look at the past to think about today, and we also look at the territory to approach it not as a space for contemplation but as a place in constant movement and in which we fulfill roles that affect and transform.

Related Topics

May interest you

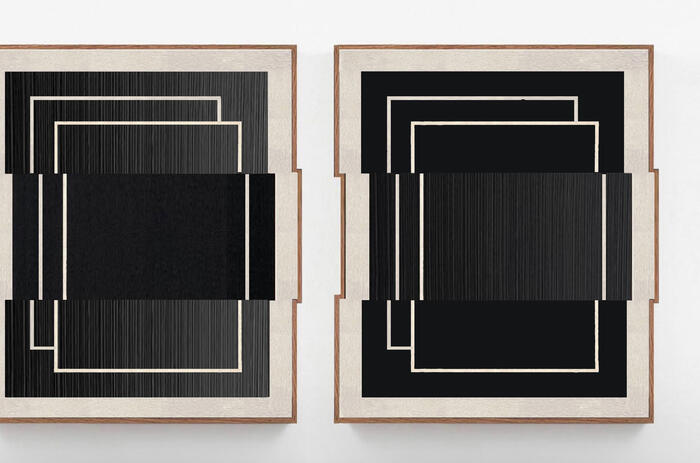

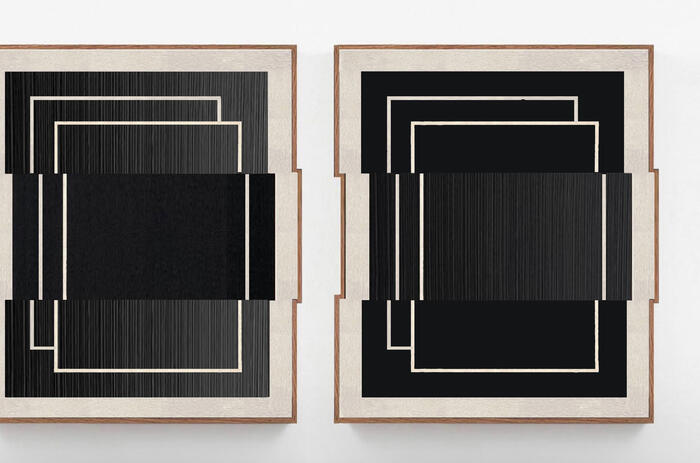

Vibración Pura (Pure Vibration) is Jesús Rafael Soto’s solo exhibition at Ascaso Gallery.

PURE VIBRATIONS. SOTO’S 100TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATIONS

Vibración Pura (Pure Vibration) is Jesús Rafael Soto’s solo exhibition at Ascaso Gallery.

PURE VIBRATIONS. SOTO’S 100TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATIONS

The Bass presents Hernan Bas: The Conceptualists, an exhibition on-view beginning December 4, 2023 that explores conceptual art as a permissive realm for creative behavior and an inviting space for queerness.

The Buenos Aires-based gallery Futbolitis is teaming up with (RE)BOOT, a new brand championing sustainability through sport, to present Tiempo Extra (Extra Time), an exhibition at Miami Design District.

ICA Miami presents the first solo museum presentation for New York–based artist Sasha Gordon, Surrogate Self. The surreal paintings and drawings that Gordon creates explore the complexities of bodily experience in gorgeous and hyper-realistic detail.

SASHA GORDON’S SURREAL SCENES AT ICA MIAMI

ICA Miami presents the first solo museum presentation for New York–based artist Sasha Gordon, Surrogate Self. The surreal paintings and drawings that Gordon creates explore the complexities of bodily experience in gorgeous and hyper-realistic detail.

Since the D+C Foundation’s Residency Program started –in 2022–, mid-career artists such as Sandra Monterroso, Jeronimo Villa, Guillermo García Cruz, Youdhisthir Maharjan and Loris Cecchini participated. The 2024 selected residents will be announced soon.

D+C FOUNDATION ARTISTS-IN-RESIDENCE PROGRAM

Since the D+C Foundation’s Residency Program started –in 2022–, mid-career artists such as Sandra Monterroso, Jeronimo Villa, Guillermo García Cruz, Youdhisthir Maharjan and Loris Cecchini participated. The 2024 selected residents will be announced soon.

Vital and veiled: Valerie Brathwaite and José Gabriel Fernández is ISLAA Artist Seminar Initiative exhibition at the University Galleries of the University of Florida. Curated by Jesús Fuenmayor and Kaira Cabañas.

Laundromat Art Space presented Worlds Behind You, the debut solo exhibition by Miami-based artist Melissa Wallen. Curated by Ray-Anthony Eddie, the presentation comprises several new and recent works from the artist’s ongoing series of dream-like “portal” paintings.

MELISSA WALLEN’S PORTAL PAINTINGS

Laundromat Art Space presented Worlds Behind You, the debut solo exhibition by Miami-based artist Melissa Wallen. Curated by Ray-Anthony Eddie, the presentation comprises several new and recent works from the artist’s ongoing series of dream-like “portal” paintings.

Amazonia is a Pinta Miami project curated by Félix Suazo that proposes a visual expedition through the Amazon, crossing countries, cultures and ecological identities. As a Special Project, Amazonia emphasizes Pinta's commitment as an international platform for Latin American art.

PINTA MIAMI 2023: A PORTAL TO THE AMAZON

Amazonia is a Pinta Miami project curated by Félix Suazo that proposes a visual expedition through the Amazon, crossing countries, cultures and ecological identities. As a Special Project, Amazonia emphasizes Pinta's commitment as an international platform for Latin American art.

NSU ART Museum Fort Lauderdale presented Glory of the World: Color Field Painting, an exhibition exploring Color Field, a tendency in mid-twentieth century American abstract painting in which vast areas of color appear as the dominating force.

THE DOMINATING FORCE OF COLORS AT NSU ART MUSEUM

NSU ART Museum Fort Lauderdale presented Glory of the World: Color Field Painting, an exhibition exploring Color Field, a tendency in mid-twentieth century American abstract painting in which vast areas of color appear as the dominating force.

Marquez Art Projects presents Cusp, a new body of work by José Delgado Zuñiga. In dynamic paintings and drawings that explode with surreal, humorous and intensely personal images, Zuñiga reflects the complexities of Chicano experiences, with a focus on the formation of identity and freedom.

JOSÉ DELGADO ZUÑIGA’S SOLO EXHIBITION AT MAP

Marquez Art Projects presents Cusp, a new body of work by José Delgado Zuñiga. In dynamic paintings and drawings that explode with surreal, humorous and intensely personal images, Zuñiga reflects the complexities of Chicano experiences, with a focus on the formation of identity and freedom.

Born in Venezuela, Antonio Briceño is a photographer and biologist. His series Dioses de América. Panteón natural (Gods of America. Natural Pantheon) participates in the Special Project Amazonia of Pinta Miami 2023. He has been working for more than 20 years on this series, whose purpose is to make visible the indigenous mythologies that have survived Christianity and colonialism, but are still in danger of extinction.

ANTONIO BRICEÑO REFLECTS ON THE VULNERABILITY AND SPLENDOR OF INDIGENOUS CULTURES

Born in Venezuela, Antonio Briceño is a photographer and biologist. His series Dioses de América. Panteón natural (Gods of America. Natural Pantheon) participates in the Special Project Amazonia of Pinta Miami 2023. He has been working for more than 20 years on this series, whose purpose is to make visible the indigenous mythologies that have survived Christianity and colonialism, but are still in danger of extinction.

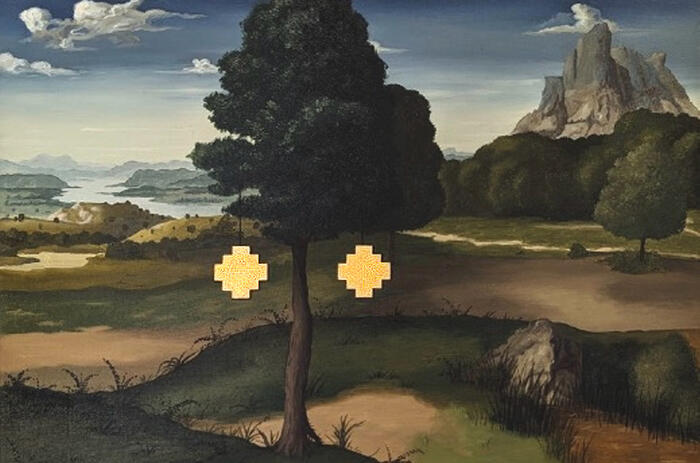

ROSAS Ek Balam gallery, based in Buenos Aires, presents works by Vicente Grondona and Max Gómez Canle in the RADAR section of Pinta Miami. Entitled Épica del paisaje (Epic of Landscape), this exhibition invokes the fragmentation of reality.

INFINITE REALITIES OF GRONDONA AND GÓMEZ CANLE ON PINTA'S RADAR

ROSAS Ek Balam gallery, based in Buenos Aires, presents works by Vicente Grondona and Max Gómez Canle in the RADAR section of Pinta Miami. Entitled Épica del paisaje (Epic of Landscape), this exhibition invokes the fragmentation of reality.

In her practice, Brazilian artist Manoela Medeiros questions artistic media by going beyond their conventional formats, producing paintings and in situ installations that explore the relationships between space, time, and the corporeality of art and of the viewer. Together with Felipe Cohen, they are part of Kubik Gallery’s proposal for Pinta Miami 2023.

MANOELA MEDEIROS ESCAPES ARTISTIC DEFINITIONS AND EXPLORES THE EVOLUTION OF THE NON-PLACE

In her practice, Brazilian artist Manoela Medeiros questions artistic media by going beyond their conventional formats, producing paintings and in situ installations that explore the relationships between space, time, and the corporeality of art and of the viewer. Together with Felipe Cohen, they are part of Kubik Gallery’s proposal for Pinta Miami 2023.

Argentine artist Trinidad Metz Brea is part of the 2023 edition of Pinta Miami, within the NEXT section that presents emerging artists from Latin America. In an interview with Arte al Día, she explores the contradictions and challenges of our present and how this is the seedbed for her sculptures, murals and post-human figures.

POST-HUMANISM AND COLLABORATION. AN INTERVIEW WITH TRINIDAD METZ BREA

Argentine artist Trinidad Metz Brea is part of the 2023 edition of Pinta Miami, within the NEXT section that presents emerging artists from Latin America. In an interview with Arte al Día, she explores the contradictions and challenges of our present and how this is the seedbed for her sculptures, murals and post-human figures.

Until December 10, 2023, the 17th edition of Pinta Miami will be held at The Hangar in Coconut Grove. Artists, gallerists, collectors, art lovers and curators will gather to get to know the best of the work of Latin American creators.

THE LATIN AMERICAN IMAGINARIUM IN PINTA MIAMI 2023

Until December 10, 2023, the 17th edition of Pinta Miami will be held at The Hangar in Coconut Grove. Artists, gallerists, collectors, art lovers and curators will gather to get to know the best of the work of Latin American creators.

As part of the curatorial proposal of Pinta Miami 2023, there are five Special Projects to honor different artistic identities.

SPECIAL PROJECTS: DIFFERENT ARTISTIC IDENTITIES AT PINTA MIAMI 2023

As part of the curatorial proposal of Pinta Miami 2023, there are five Special Projects to honor different artistic identities.

Pinta Miami 2023 closed its 17th edition celebrating Latin American art with artists, curators, collectors and a large number of visitors and art lovers.

PINTA MIAMI 2023 – A MEETING AND DIFFUSION EPICENTER

Pinta Miami 2023 closed its 17th edition celebrating Latin American art with artists, curators, collectors and a large number of visitors and art lovers.

Independent Curators International (ICI) is now accepting applications for the 2024 Curatorial Research Fellowships.

CALL FOR APPLICATIONS: CURATORIAL RESEARCH FELLOWSHIPS

Independent Curators International (ICI) is now accepting applications for the 2024 Curatorial Research Fellowships.

La Otra Verdad (The Other Truth), the most recent individual exhibition of the artist Harry Chavez, is presented at the Ricardo Palma Cultural Center.

THE HYPNOTIC CREATURES OF HARRY CHAVEZ

La Otra Verdad (The Other Truth), the most recent individual exhibition of the artist Harry Chavez, is presented at the Ricardo Palma Cultural Center.

The Museo de Arte de Lima (MALI) and proyectoamil present Evoking a Space Beyond Cinema, the first monographic museum exhibition by Rosa Barba in Peru.

EVOKING A SPACE BEYOND CINEMA: ROSA BARBA IN PERU

The Museo de Arte de Lima (MALI) and proyectoamil present Evoking a Space Beyond Cinema, the first monographic museum exhibition by Rosa Barba in Peru.

Pinta PArC returns with a new edition: from April 24 to 28 at Casa Prado Miraflores, the fair will present an experimental and ambitious program, along with a careful selection of galleries.

PINTA PArC 2024 REAFFIRMS ITS COMMITMENT TO DISSEMINATE THE REGION'S ARTISTIC IDENTITIES

Pinta PArC returns with a new edition: from April 24 to 28 at Casa Prado Miraflores, the fair will present an experimental and ambitious program, along with a careful selection of galleries.

Vibración Pura (Pure Vibration) is Jesús Rafael Soto’s solo exhibition at Ascaso Gallery.

PURE VIBRATIONS. SOTO’S 100TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATIONS

The Bass presents Hernan Bas: The Conceptualists, an exhibition on-view beginning December 4, 2023 that explores conceptual art as a permissive realm for creative behavior and an inviting space for queerness.

The Buenos Aires-based gallery Futbolitis is teaming up with (RE)BOOT, a new brand championing sustainability through sport, to present Tiempo Extra (Extra Time), an exhibition at Miami Design District.

ICA Miami presents the first solo museum presentation for New York–based artist Sasha Gordon, Surrogate Self. The surreal paintings and drawings that Gordon creates explore the complexities of bodily experience in gorgeous and hyper-realistic detail.

SASHA GORDON’S SURREAL SCENES AT ICA MIAMI

ICA Miami presents the first solo museum presentation for New York–based artist Sasha Gordon, Surrogate Self. The surreal paintings and drawings that Gordon creates explore the complexities of bodily experience in gorgeous and hyper-realistic detail.

Since the D+C Foundation’s Residency Program started –in 2022–, mid-career artists such as Sandra Monterroso, Jeronimo Villa, Guillermo García Cruz, Youdhisthir Maharjan and Loris Cecchini participated. The 2024 selected residents will be announced soon.

D+C FOUNDATION ARTISTS-IN-RESIDENCE PROGRAM

Since the D+C Foundation’s Residency Program started –in 2022–, mid-career artists such as Sandra Monterroso, Jeronimo Villa, Guillermo García Cruz, Youdhisthir Maharjan and Loris Cecchini participated. The 2024 selected residents will be announced soon.

Vital and veiled: Valerie Brathwaite and José Gabriel Fernández is ISLAA Artist Seminar Initiative exhibition at the University Galleries of the University of Florida. Curated by Jesús Fuenmayor and Kaira Cabañas.

Laundromat Art Space presented Worlds Behind You, the debut solo exhibition by Miami-based artist Melissa Wallen. Curated by Ray-Anthony Eddie, the presentation comprises several new and recent works from the artist’s ongoing series of dream-like “portal” paintings.

MELISSA WALLEN’S PORTAL PAINTINGS

Laundromat Art Space presented Worlds Behind You, the debut solo exhibition by Miami-based artist Melissa Wallen. Curated by Ray-Anthony Eddie, the presentation comprises several new and recent works from the artist’s ongoing series of dream-like “portal” paintings.

Amazonia is a Pinta Miami project curated by Félix Suazo that proposes a visual expedition through the Amazon, crossing countries, cultures and ecological identities. As a Special Project, Amazonia emphasizes Pinta's commitment as an international platform for Latin American art.

PINTA MIAMI 2023: A PORTAL TO THE AMAZON

Amazonia is a Pinta Miami project curated by Félix Suazo that proposes a visual expedition through the Amazon, crossing countries, cultures and ecological identities. As a Special Project, Amazonia emphasizes Pinta's commitment as an international platform for Latin American art.

NSU ART Museum Fort Lauderdale presented Glory of the World: Color Field Painting, an exhibition exploring Color Field, a tendency in mid-twentieth century American abstract painting in which vast areas of color appear as the dominating force.

THE DOMINATING FORCE OF COLORS AT NSU ART MUSEUM

NSU ART Museum Fort Lauderdale presented Glory of the World: Color Field Painting, an exhibition exploring Color Field, a tendency in mid-twentieth century American abstract painting in which vast areas of color appear as the dominating force.

Marquez Art Projects presents Cusp, a new body of work by José Delgado Zuñiga. In dynamic paintings and drawings that explode with surreal, humorous and intensely personal images, Zuñiga reflects the complexities of Chicano experiences, with a focus on the formation of identity and freedom.

JOSÉ DELGADO ZUÑIGA’S SOLO EXHIBITION AT MAP

Marquez Art Projects presents Cusp, a new body of work by José Delgado Zuñiga. In dynamic paintings and drawings that explode with surreal, humorous and intensely personal images, Zuñiga reflects the complexities of Chicano experiences, with a focus on the formation of identity and freedom.

Born in Venezuela, Antonio Briceño is a photographer and biologist. His series Dioses de América. Panteón natural (Gods of America. Natural Pantheon) participates in the Special Project Amazonia of Pinta Miami 2023. He has been working for more than 20 years on this series, whose purpose is to make visible the indigenous mythologies that have survived Christianity and colonialism, but are still in danger of extinction.

ANTONIO BRICEÑO REFLECTS ON THE VULNERABILITY AND SPLENDOR OF INDIGENOUS CULTURES

Born in Venezuela, Antonio Briceño is a photographer and biologist. His series Dioses de América. Panteón natural (Gods of America. Natural Pantheon) participates in the Special Project Amazonia of Pinta Miami 2023. He has been working for more than 20 years on this series, whose purpose is to make visible the indigenous mythologies that have survived Christianity and colonialism, but are still in danger of extinction.

ROSAS Ek Balam gallery, based in Buenos Aires, presents works by Vicente Grondona and Max Gómez Canle in the RADAR section of Pinta Miami. Entitled Épica del paisaje (Epic of Landscape), this exhibition invokes the fragmentation of reality.

INFINITE REALITIES OF GRONDONA AND GÓMEZ CANLE ON PINTA'S RADAR

ROSAS Ek Balam gallery, based in Buenos Aires, presents works by Vicente Grondona and Max Gómez Canle in the RADAR section of Pinta Miami. Entitled Épica del paisaje (Epic of Landscape), this exhibition invokes the fragmentation of reality.

In her practice, Brazilian artist Manoela Medeiros questions artistic media by going beyond their conventional formats, producing paintings and in situ installations that explore the relationships between space, time, and the corporeality of art and of the viewer. Together with Felipe Cohen, they are part of Kubik Gallery’s proposal for Pinta Miami 2023.

MANOELA MEDEIROS ESCAPES ARTISTIC DEFINITIONS AND EXPLORES THE EVOLUTION OF THE NON-PLACE

In her practice, Brazilian artist Manoela Medeiros questions artistic media by going beyond their conventional formats, producing paintings and in situ installations that explore the relationships between space, time, and the corporeality of art and of the viewer. Together with Felipe Cohen, they are part of Kubik Gallery’s proposal for Pinta Miami 2023.

Argentine artist Trinidad Metz Brea is part of the 2023 edition of Pinta Miami, within the NEXT section that presents emerging artists from Latin America. In an interview with Arte al Día, she explores the contradictions and challenges of our present and how this is the seedbed for her sculptures, murals and post-human figures.

POST-HUMANISM AND COLLABORATION. AN INTERVIEW WITH TRINIDAD METZ BREA

Argentine artist Trinidad Metz Brea is part of the 2023 edition of Pinta Miami, within the NEXT section that presents emerging artists from Latin America. In an interview with Arte al Día, she explores the contradictions and challenges of our present and how this is the seedbed for her sculptures, murals and post-human figures.

Until December 10, 2023, the 17th edition of Pinta Miami will be held at The Hangar in Coconut Grove. Artists, gallerists, collectors, art lovers and curators will gather to get to know the best of the work of Latin American creators.

THE LATIN AMERICAN IMAGINARIUM IN PINTA MIAMI 2023

Until December 10, 2023, the 17th edition of Pinta Miami will be held at The Hangar in Coconut Grove. Artists, gallerists, collectors, art lovers and curators will gather to get to know the best of the work of Latin American creators.

As part of the curatorial proposal of Pinta Miami 2023, there are five Special Projects to honor different artistic identities.

SPECIAL PROJECTS: DIFFERENT ARTISTIC IDENTITIES AT PINTA MIAMI 2023

As part of the curatorial proposal of Pinta Miami 2023, there are five Special Projects to honor different artistic identities.

Pinta Miami 2023 closed its 17th edition celebrating Latin American art with artists, curators, collectors and a large number of visitors and art lovers.

PINTA MIAMI 2023 – A MEETING AND DIFFUSION EPICENTER

Pinta Miami 2023 closed its 17th edition celebrating Latin American art with artists, curators, collectors and a large number of visitors and art lovers.

Independent Curators International (ICI) is now accepting applications for the 2024 Curatorial Research Fellowships.

CALL FOR APPLICATIONS: CURATORIAL RESEARCH FELLOWSHIPS

Independent Curators International (ICI) is now accepting applications for the 2024 Curatorial Research Fellowships.

La Otra Verdad (The Other Truth), the most recent individual exhibition of the artist Harry Chavez, is presented at the Ricardo Palma Cultural Center.

THE HYPNOTIC CREATURES OF HARRY CHAVEZ

La Otra Verdad (The Other Truth), the most recent individual exhibition of the artist Harry Chavez, is presented at the Ricardo Palma Cultural Center.

The Museo de Arte de Lima (MALI) and proyectoamil present Evoking a Space Beyond Cinema, the first monographic museum exhibition by Rosa Barba in Peru.

EVOKING A SPACE BEYOND CINEMA: ROSA BARBA IN PERU

The Museo de Arte de Lima (MALI) and proyectoamil present Evoking a Space Beyond Cinema, the first monographic museum exhibition by Rosa Barba in Peru.

Pinta PArC returns with a new edition: from April 24 to 28 at Casa Prado Miraflores, the fair will present an experimental and ambitious program, along with a careful selection of galleries.

PINTA PArC 2024 REAFFIRMS ITS COMMITMENT TO DISSEMINATE THE REGION'S ARTISTIC IDENTITIES

Pinta PArC returns with a new edition: from April 24 to 28 at Casa Prado Miraflores, the fair will present an experimental and ambitious program, along with a careful selection of galleries.

Vibración Pura (Pure Vibration) is Jesús Rafael Soto’s solo exhibition at Ascaso Gallery.

PURE VIBRATIONS. SOTO’S 100TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATIONS

The Bass presents Hernan Bas: The Conceptualists, an exhibition on-view beginning December 4, 2023 that explores conceptual art as a permissive realm for creative behavior and an inviting space for queerness.

The Buenos Aires-based gallery Futbolitis is teaming up with (RE)BOOT, a new brand championing sustainability through sport, to present Tiempo Extra (Extra Time), an exhibition at Miami Design District.

ICA Miami presents the first solo museum presentation for New York–based artist Sasha Gordon, Surrogate Self. The surreal paintings and drawings that Gordon creates explore the complexities of bodily experience in gorgeous and hyper-realistic detail.

SASHA GORDON’S SURREAL SCENES AT ICA MIAMI

ICA Miami presents the first solo museum presentation for New York–based artist Sasha Gordon, Surrogate Self. The surreal paintings and drawings that Gordon creates explore the complexities of bodily experience in gorgeous and hyper-realistic detail.

Since the D+C Foundation’s Residency Program started –in 2022–, mid-career artists such as Sandra Monterroso, Jeronimo Villa, Guillermo García Cruz, Youdhisthir Maharjan and Loris Cecchini participated. The 2024 selected residents will be announced soon.

D+C FOUNDATION ARTISTS-IN-RESIDENCE PROGRAM

Since the D+C Foundation’s Residency Program started –in 2022–, mid-career artists such as Sandra Monterroso, Jeronimo Villa, Guillermo García Cruz, Youdhisthir Maharjan and Loris Cecchini participated. The 2024 selected residents will be announced soon.

Vital and veiled: Valerie Brathwaite and José Gabriel Fernández is ISLAA Artist Seminar Initiative exhibition at the University Galleries of the University of Florida. Curated by Jesús Fuenmayor and Kaira Cabañas.

Laundromat Art Space presented Worlds Behind You, the debut solo exhibition by Miami-based artist Melissa Wallen. Curated by Ray-Anthony Eddie, the presentation comprises several new and recent works from the artist’s ongoing series of dream-like “portal” paintings.

MELISSA WALLEN’S PORTAL PAINTINGS

Laundromat Art Space presented Worlds Behind You, the debut solo exhibition by Miami-based artist Melissa Wallen. Curated by Ray-Anthony Eddie, the presentation comprises several new and recent works from the artist’s ongoing series of dream-like “portal” paintings.

Amazonia is a Pinta Miami project curated by Félix Suazo that proposes a visual expedition through the Amazon, crossing countries, cultures and ecological identities. As a Special Project, Amazonia emphasizes Pinta's commitment as an international platform for Latin American art.

PINTA MIAMI 2023: A PORTAL TO THE AMAZON

Amazonia is a Pinta Miami project curated by Félix Suazo that proposes a visual expedition through the Amazon, crossing countries, cultures and ecological identities. As a Special Project, Amazonia emphasizes Pinta's commitment as an international platform for Latin American art.

NSU ART Museum Fort Lauderdale presented Glory of the World: Color Field Painting, an exhibition exploring Color Field, a tendency in mid-twentieth century American abstract painting in which vast areas of color appear as the dominating force.

THE DOMINATING FORCE OF COLORS AT NSU ART MUSEUM

NSU ART Museum Fort Lauderdale presented Glory of the World: Color Field Painting, an exhibition exploring Color Field, a tendency in mid-twentieth century American abstract painting in which vast areas of color appear as the dominating force.

Marquez Art Projects presents Cusp, a new body of work by José Delgado Zuñiga. In dynamic paintings and drawings that explode with surreal, humorous and intensely personal images, Zuñiga reflects the complexities of Chicano experiences, with a focus on the formation of identity and freedom.

JOSÉ DELGADO ZUÑIGA’S SOLO EXHIBITION AT MAP

Marquez Art Projects presents Cusp, a new body of work by José Delgado Zuñiga. In dynamic paintings and drawings that explode with surreal, humorous and intensely personal images, Zuñiga reflects the complexities of Chicano experiences, with a focus on the formation of identity and freedom.

Born in Venezuela, Antonio Briceño is a photographer and biologist. His series Dioses de América. Panteón natural (Gods of America. Natural Pantheon) participates in the Special Project Amazonia of Pinta Miami 2023. He has been working for more than 20 years on this series, whose purpose is to make visible the indigenous mythologies that have survived Christianity and colonialism, but are still in danger of extinction.

ANTONIO BRICEÑO REFLECTS ON THE VULNERABILITY AND SPLENDOR OF INDIGENOUS CULTURES

Born in Venezuela, Antonio Briceño is a photographer and biologist. His series Dioses de América. Panteón natural (Gods of America. Natural Pantheon) participates in the Special Project Amazonia of Pinta Miami 2023. He has been working for more than 20 years on this series, whose purpose is to make visible the indigenous mythologies that have survived Christianity and colonialism, but are still in danger of extinction.

ROSAS Ek Balam gallery, based in Buenos Aires, presents works by Vicente Grondona and Max Gómez Canle in the RADAR section of Pinta Miami. Entitled Épica del paisaje (Epic of Landscape), this exhibition invokes the fragmentation of reality.

INFINITE REALITIES OF GRONDONA AND GÓMEZ CANLE ON PINTA'S RADAR

ROSAS Ek Balam gallery, based in Buenos Aires, presents works by Vicente Grondona and Max Gómez Canle in the RADAR section of Pinta Miami. Entitled Épica del paisaje (Epic of Landscape), this exhibition invokes the fragmentation of reality.

In her practice, Brazilian artist Manoela Medeiros questions artistic media by going beyond their conventional formats, producing paintings and in situ installations that explore the relationships between space, time, and the corporeality of art and of the viewer. Together with Felipe Cohen, they are part of Kubik Gallery’s proposal for Pinta Miami 2023.

MANOELA MEDEIROS ESCAPES ARTISTIC DEFINITIONS AND EXPLORES THE EVOLUTION OF THE NON-PLACE

In her practice, Brazilian artist Manoela Medeiros questions artistic media by going beyond their conventional formats, producing paintings and in situ installations that explore the relationships between space, time, and the corporeality of art and of the viewer. Together with Felipe Cohen, they are part of Kubik Gallery’s proposal for Pinta Miami 2023.

Argentine artist Trinidad Metz Brea is part of the 2023 edition of Pinta Miami, within the NEXT section that presents emerging artists from Latin America. In an interview with Arte al Día, she explores the contradictions and challenges of our present and how this is the seedbed for her sculptures, murals and post-human figures.

POST-HUMANISM AND COLLABORATION. AN INTERVIEW WITH TRINIDAD METZ BREA

Argentine artist Trinidad Metz Brea is part of the 2023 edition of Pinta Miami, within the NEXT section that presents emerging artists from Latin America. In an interview with Arte al Día, she explores the contradictions and challenges of our present and how this is the seedbed for her sculptures, murals and post-human figures.

Until December 10, 2023, the 17th edition of Pinta Miami will be held at The Hangar in Coconut Grove. Artists, gallerists, collectors, art lovers and curators will gather to get to know the best of the work of Latin American creators.

THE LATIN AMERICAN IMAGINARIUM IN PINTA MIAMI 2023

Until December 10, 2023, the 17th edition of Pinta Miami will be held at The Hangar in Coconut Grove. Artists, gallerists, collectors, art lovers and curators will gather to get to know the best of the work of Latin American creators.

As part of the curatorial proposal of Pinta Miami 2023, there are five Special Projects to honor different artistic identities.

SPECIAL PROJECTS: DIFFERENT ARTISTIC IDENTITIES AT PINTA MIAMI 2023

As part of the curatorial proposal of Pinta Miami 2023, there are five Special Projects to honor different artistic identities.

Pinta Miami 2023 closed its 17th edition celebrating Latin American art with artists, curators, collectors and a large number of visitors and art lovers.

PINTA MIAMI 2023 – A MEETING AND DIFFUSION EPICENTER

Pinta Miami 2023 closed its 17th edition celebrating Latin American art with artists, curators, collectors and a large number of visitors and art lovers.

Independent Curators International (ICI) is now accepting applications for the 2024 Curatorial Research Fellowships.

CALL FOR APPLICATIONS: CURATORIAL RESEARCH FELLOWSHIPS

Independent Curators International (ICI) is now accepting applications for the 2024 Curatorial Research Fellowships.

La Otra Verdad (The Other Truth), the most recent individual exhibition of the artist Harry Chavez, is presented at the Ricardo Palma Cultural Center.

THE HYPNOTIC CREATURES OF HARRY CHAVEZ

La Otra Verdad (The Other Truth), the most recent individual exhibition of the artist Harry Chavez, is presented at the Ricardo Palma Cultural Center.

The Museo de Arte de Lima (MALI) and proyectoamil present Evoking a Space Beyond Cinema, the first monographic museum exhibition by Rosa Barba in Peru.

EVOKING A SPACE BEYOND CINEMA: ROSA BARBA IN PERU

The Museo de Arte de Lima (MALI) and proyectoamil present Evoking a Space Beyond Cinema, the first monographic museum exhibition by Rosa Barba in Peru.

Pinta PArC returns with a new edition: from April 24 to 28 at Casa Prado Miraflores, the fair will present an experimental and ambitious program, along with a careful selection of galleries.

PINTA PArC 2024 REAFFIRMS ITS COMMITMENT TO DISSEMINATE THE REGION'S ARTISTIC IDENTITIES

Pinta PArC returns with a new edition: from April 24 to 28 at Casa Prado Miraflores, the fair will present an experimental and ambitious program, along with a careful selection of galleries.

Vibración Pura (Pure Vibration) is Jesús Rafael Soto’s solo exhibition at Ascaso Gallery.

PURE VIBRATIONS. SOTO’S 100TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATIONS

The Bass presents Hernan Bas: The Conceptualists, an exhibition on-view beginning December 4, 2023 that explores conceptual art as a permissive realm for creative behavior and an inviting space for queerness.

The Buenos Aires-based gallery Futbolitis is teaming up with (RE)BOOT, a new brand championing sustainability through sport, to present Tiempo Extra (Extra Time), an exhibition at Miami Design District.

ICA Miami presents the first solo museum presentation for New York–based artist Sasha Gordon, Surrogate Self. The surreal paintings and drawings that Gordon creates explore the complexities of bodily experience in gorgeous and hyper-realistic detail.

SASHA GORDON’S SURREAL SCENES AT ICA MIAMI

ICA Miami presents the first solo museum presentation for New York–based artist Sasha Gordon, Surrogate Self. The surreal paintings and drawings that Gordon creates explore the complexities of bodily experience in gorgeous and hyper-realistic detail.

Since the D+C Foundation’s Residency Program started –in 2022–, mid-career artists such as Sandra Monterroso, Jeronimo Villa, Guillermo García Cruz, Youdhisthir Maharjan and Loris Cecchini participated. The 2024 selected residents will be announced soon.

D+C FOUNDATION ARTISTS-IN-RESIDENCE PROGRAM

Since the D+C Foundation’s Residency Program started –in 2022–, mid-career artists such as Sandra Monterroso, Jeronimo Villa, Guillermo García Cruz, Youdhisthir Maharjan and Loris Cecchini participated. The 2024 selected residents will be announced soon.

Vital and veiled: Valerie Brathwaite and José Gabriel Fernández is ISLAA Artist Seminar Initiative exhibition at the University Galleries of the University of Florida. Curated by Jesús Fuenmayor and Kaira Cabañas.

Laundromat Art Space presented Worlds Behind You, the debut solo exhibition by Miami-based artist Melissa Wallen. Curated by Ray-Anthony Eddie, the presentation comprises several new and recent works from the artist’s ongoing series of dream-like “portal” paintings.

MELISSA WALLEN’S PORTAL PAINTINGS

Laundromat Art Space presented Worlds Behind You, the debut solo exhibition by Miami-based artist Melissa Wallen. Curated by Ray-Anthony Eddie, the presentation comprises several new and recent works from the artist’s ongoing series of dream-like “portal” paintings.

Amazonia is a Pinta Miami project curated by Félix Suazo that proposes a visual expedition through the Amazon, crossing countries, cultures and ecological identities. As a Special Project, Amazonia emphasizes Pinta's commitment as an international platform for Latin American art.

PINTA MIAMI 2023: A PORTAL TO THE AMAZON

Amazonia is a Pinta Miami project curated by Félix Suazo that proposes a visual expedition through the Amazon, crossing countries, cultures and ecological identities. As a Special Project, Amazonia emphasizes Pinta's commitment as an international platform for Latin American art.

NSU ART Museum Fort Lauderdale presented Glory of the World: Color Field Painting, an exhibition exploring Color Field, a tendency in mid-twentieth century American abstract painting in which vast areas of color appear as the dominating force.

THE DOMINATING FORCE OF COLORS AT NSU ART MUSEUM

NSU ART Museum Fort Lauderdale presented Glory of the World: Color Field Painting, an exhibition exploring Color Field, a tendency in mid-twentieth century American abstract painting in which vast areas of color appear as the dominating force.

Marquez Art Projects presents Cusp, a new body of work by José Delgado Zuñiga. In dynamic paintings and drawings that explode with surreal, humorous and intensely personal images, Zuñiga reflects the complexities of Chicano experiences, with a focus on the formation of identity and freedom.

JOSÉ DELGADO ZUÑIGA’S SOLO EXHIBITION AT MAP

Marquez Art Projects presents Cusp, a new body of work by José Delgado Zuñiga. In dynamic paintings and drawings that explode with surreal, humorous and intensely personal images, Zuñiga reflects the complexities of Chicano experiences, with a focus on the formation of identity and freedom.

Born in Venezuela, Antonio Briceño is a photographer and biologist. His series Dioses de América. Panteón natural (Gods of America. Natural Pantheon) participates in the Special Project Amazonia of Pinta Miami 2023. He has been working for more than 20 years on this series, whose purpose is to make visible the indigenous mythologies that have survived Christianity and colonialism, but are still in danger of extinction.

ANTONIO BRICEÑO REFLECTS ON THE VULNERABILITY AND SPLENDOR OF INDIGENOUS CULTURES

Born in Venezuela, Antonio Briceño is a photographer and biologist. His series Dioses de América. Panteón natural (Gods of America. Natural Pantheon) participates in the Special Project Amazonia of Pinta Miami 2023. He has been working for more than 20 years on this series, whose purpose is to make visible the indigenous mythologies that have survived Christianity and colonialism, but are still in danger of extinction.

ROSAS Ek Balam gallery, based in Buenos Aires, presents works by Vicente Grondona and Max Gómez Canle in the RADAR section of Pinta Miami. Entitled Épica del paisaje (Epic of Landscape), this exhibition invokes the fragmentation of reality.

INFINITE REALITIES OF GRONDONA AND GÓMEZ CANLE ON PINTA'S RADAR

ROSAS Ek Balam gallery, based in Buenos Aires, presents works by Vicente Grondona and Max Gómez Canle in the RADAR section of Pinta Miami. Entitled Épica del paisaje (Epic of Landscape), this exhibition invokes the fragmentation of reality.

In her practice, Brazilian artist Manoela Medeiros questions artistic media by going beyond their conventional formats, producing paintings and in situ installations that explore the relationships between space, time, and the corporeality of art and of the viewer. Together with Felipe Cohen, they are part of Kubik Gallery’s proposal for Pinta Miami 2023.

MANOELA MEDEIROS ESCAPES ARTISTIC DEFINITIONS AND EXPLORES THE EVOLUTION OF THE NON-PLACE

In her practice, Brazilian artist Manoela Medeiros questions artistic media by going beyond their conventional formats, producing paintings and in situ installations that explore the relationships between space, time, and the corporeality of art and of the viewer. Together with Felipe Cohen, they are part of Kubik Gallery’s proposal for Pinta Miami 2023.

Argentine artist Trinidad Metz Brea is part of the 2023 edition of Pinta Miami, within the NEXT section that presents emerging artists from Latin America. In an interview with Arte al Día, she explores the contradictions and challenges of our present and how this is the seedbed for her sculptures, murals and post-human figures.

POST-HUMANISM AND COLLABORATION. AN INTERVIEW WITH TRINIDAD METZ BREA

Argentine artist Trinidad Metz Brea is part of the 2023 edition of Pinta Miami, within the NEXT section that presents emerging artists from Latin America. In an interview with Arte al Día, she explores the contradictions and challenges of our present and how this is the seedbed for her sculptures, murals and post-human figures.

Until December 10, 2023, the 17th edition of Pinta Miami will be held at The Hangar in Coconut Grove. Artists, gallerists, collectors, art lovers and curators will gather to get to know the best of the work of Latin American creators.

THE LATIN AMERICAN IMAGINARIUM IN PINTA MIAMI 2023

Until December 10, 2023, the 17th edition of Pinta Miami will be held at The Hangar in Coconut Grove. Artists, gallerists, collectors, art lovers and curators will gather to get to know the best of the work of Latin American creators.

As part of the curatorial proposal of Pinta Miami 2023, there are five Special Projects to honor different artistic identities.

SPECIAL PROJECTS: DIFFERENT ARTISTIC IDENTITIES AT PINTA MIAMI 2023

As part of the curatorial proposal of Pinta Miami 2023, there are five Special Projects to honor different artistic identities.

Pinta Miami 2023 closed its 17th edition celebrating Latin American art with artists, curators, collectors and a large number of visitors and art lovers.

PINTA MIAMI 2023 – A MEETING AND DIFFUSION EPICENTER

Pinta Miami 2023 closed its 17th edition celebrating Latin American art with artists, curators, collectors and a large number of visitors and art lovers.

Independent Curators International (ICI) is now accepting applications for the 2024 Curatorial Research Fellowships.

CALL FOR APPLICATIONS: CURATORIAL RESEARCH FELLOWSHIPS

Independent Curators International (ICI) is now accepting applications for the 2024 Curatorial Research Fellowships.

La Otra Verdad (The Other Truth), the most recent individual exhibition of the artist Harry Chavez, is presented at the Ricardo Palma Cultural Center.

THE HYPNOTIC CREATURES OF HARRY CHAVEZ

La Otra Verdad (The Other Truth), the most recent individual exhibition of the artist Harry Chavez, is presented at the Ricardo Palma Cultural Center.

The Museo de Arte de Lima (MALI) and proyectoamil present Evoking a Space Beyond Cinema, the first monographic museum exhibition by Rosa Barba in Peru.

EVOKING A SPACE BEYOND CINEMA: ROSA BARBA IN PERU

The Museo de Arte de Lima (MALI) and proyectoamil present Evoking a Space Beyond Cinema, the first monographic museum exhibition by Rosa Barba in Peru.

Pinta PArC returns with a new edition: from April 24 to 28 at Casa Prado Miraflores, the fair will present an experimental and ambitious program, along with a careful selection of galleries.

PINTA PArC 2024 REAFFIRMS ITS COMMITMENT TO DISSEMINATE THE REGION'S ARTISTIC IDENTITIES

Pinta PArC returns with a new edition: from April 24 to 28 at Casa Prado Miraflores, the fair will present an experimental and ambitious program, along with a careful selection of galleries.

Vibración Pura (Pure Vibration) is Jesús Rafael Soto’s solo exhibition at Ascaso Gallery.

PURE VIBRATIONS. SOTO’S 100TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATIONS

The Bass presents Hernan Bas: The Conceptualists, an exhibition on-view beginning December 4, 2023 that explores conceptual art as a permissive realm for creative behavior and an inviting space for queerness.

The Buenos Aires-based gallery Futbolitis is teaming up with (RE)BOOT, a new brand championing sustainability through sport, to present Tiempo Extra (Extra Time), an exhibition at Miami Design District.

ICA Miami presents the first solo museum presentation for New York–based artist Sasha Gordon, Surrogate Self. The surreal paintings and drawings that Gordon creates explore the complexities of bodily experience in gorgeous and hyper-realistic detail.

SASHA GORDON’S SURREAL SCENES AT ICA MIAMI

ICA Miami presents the first solo museum presentation for New York–based artist Sasha Gordon, Surrogate Self. The surreal paintings and drawings that Gordon creates explore the complexities of bodily experience in gorgeous and hyper-realistic detail.

Since the D+C Foundation’s Residency Program started –in 2022–, mid-career artists such as Sandra Monterroso, Jeronimo Villa, Guillermo García Cruz, Youdhisthir Maharjan and Loris Cecchini participated. The 2024 selected residents will be announced soon.

D+C FOUNDATION ARTISTS-IN-RESIDENCE PROGRAM

Since the D+C Foundation’s Residency Program started –in 2022–, mid-career artists such as Sandra Monterroso, Jeronimo Villa, Guillermo García Cruz, Youdhisthir Maharjan and Loris Cecchini participated. The 2024 selected residents will be announced soon.

Vital and veiled: Valerie Brathwaite and José Gabriel Fernández is ISLAA Artist Seminar Initiative exhibition at the University Galleries of the University of Florida. Curated by Jesús Fuenmayor and Kaira Cabañas.

Laundromat Art Space presented Worlds Behind You, the debut solo exhibition by Miami-based artist Melissa Wallen. Curated by Ray-Anthony Eddie, the presentation comprises several new and recent works from the artist’s ongoing series of dream-like “portal” paintings.

MELISSA WALLEN’S PORTAL PAINTINGS

Laundromat Art Space presented Worlds Behind You, the debut solo exhibition by Miami-based artist Melissa Wallen. Curated by Ray-Anthony Eddie, the presentation comprises several new and recent works from the artist’s ongoing series of dream-like “portal” paintings.

Amazonia is a Pinta Miami project curated by Félix Suazo that proposes a visual expedition through the Amazon, crossing countries, cultures and ecological identities. As a Special Project, Amazonia emphasizes Pinta's commitment as an international platform for Latin American art.

PINTA MIAMI 2023: A PORTAL TO THE AMAZON

Amazonia is a Pinta Miami project curated by Félix Suazo that proposes a visual expedition through the Amazon, crossing countries, cultures and ecological identities. As a Special Project, Amazonia emphasizes Pinta's commitment as an international platform for Latin American art.

NSU ART Museum Fort Lauderdale presented Glory of the World: Color Field Painting, an exhibition exploring Color Field, a tendency in mid-twentieth century American abstract painting in which vast areas of color appear as the dominating force.

THE DOMINATING FORCE OF COLORS AT NSU ART MUSEUM

NSU ART Museum Fort Lauderdale presented Glory of the World: Color Field Painting, an exhibition exploring Color Field, a tendency in mid-twentieth century American abstract painting in which vast areas of color appear as the dominating force.

Marquez Art Projects presents Cusp, a new body of work by José Delgado Zuñiga. In dynamic paintings and drawings that explode with surreal, humorous and intensely personal images, Zuñiga reflects the complexities of Chicano experiences, with a focus on the formation of identity and freedom.

JOSÉ DELGADO ZUÑIGA’S SOLO EXHIBITION AT MAP

Marquez Art Projects presents Cusp, a new body of work by José Delgado Zuñiga. In dynamic paintings and drawings that explode with surreal, humorous and intensely personal images, Zuñiga reflects the complexities of Chicano experiences, with a focus on the formation of identity and freedom.

Born in Venezuela, Antonio Briceño is a photographer and biologist. His series Dioses de América. Panteón natural (Gods of America. Natural Pantheon) participates in the Special Project Amazonia of Pinta Miami 2023. He has been working for more than 20 years on this series, whose purpose is to make visible the indigenous mythologies that have survived Christianity and colonialism, but are still in danger of extinction.

ANTONIO BRICEÑO REFLECTS ON THE VULNERABILITY AND SPLENDOR OF INDIGENOUS CULTURES

Born in Venezuela, Antonio Briceño is a photographer and biologist. His series Dioses de América. Panteón natural (Gods of America. Natural Pantheon) participates in the Special Project Amazonia of Pinta Miami 2023. He has been working for more than 20 years on this series, whose purpose is to make visible the indigenous mythologies that have survived Christianity and colonialism, but are still in danger of extinction.

ROSAS Ek Balam gallery, based in Buenos Aires, presents works by Vicente Grondona and Max Gómez Canle in the RADAR section of Pinta Miami. Entitled Épica del paisaje (Epic of Landscape), this exhibition invokes the fragmentation of reality.

INFINITE REALITIES OF GRONDONA AND GÓMEZ CANLE ON PINTA'S RADAR

ROSAS Ek Balam gallery, based in Buenos Aires, presents works by Vicente Grondona and Max Gómez Canle in the RADAR section of Pinta Miami. Entitled Épica del paisaje (Epic of Landscape), this exhibition invokes the fragmentation of reality.

In her practice, Brazilian artist Manoela Medeiros questions artistic media by going beyond their conventional formats, producing paintings and in situ installations that explore the relationships between space, time, and the corporeality of art and of the viewer. Together with Felipe Cohen, they are part of Kubik Gallery’s proposal for Pinta Miami 2023.

MANOELA MEDEIROS ESCAPES ARTISTIC DEFINITIONS AND EXPLORES THE EVOLUTION OF THE NON-PLACE

In her practice, Brazilian artist Manoela Medeiros questions artistic media by going beyond their conventional formats, producing paintings and in situ installations that explore the relationships between space, time, and the corporeality of art and of the viewer. Together with Felipe Cohen, they are part of Kubik Gallery’s proposal for Pinta Miami 2023.

Argentine artist Trinidad Metz Brea is part of the 2023 edition of Pinta Miami, within the NEXT section that presents emerging artists from Latin America. In an interview with Arte al Día, she explores the contradictions and challenges of our present and how this is the seedbed for her sculptures, murals and post-human figures.

POST-HUMANISM AND COLLABORATION. AN INTERVIEW WITH TRINIDAD METZ BREA

Argentine artist Trinidad Metz Brea is part of the 2023 edition of Pinta Miami, within the NEXT section that presents emerging artists from Latin America. In an interview with Arte al Día, she explores the contradictions and challenges of our present and how this is the seedbed for her sculptures, murals and post-human figures.

Until December 10, 2023, the 17th edition of Pinta Miami will be held at The Hangar in Coconut Grove. Artists, gallerists, collectors, art lovers and curators will gather to get to know the best of the work of Latin American creators.

THE LATIN AMERICAN IMAGINARIUM IN PINTA MIAMI 2023

Until December 10, 2023, the 17th edition of Pinta Miami will be held at The Hangar in Coconut Grove. Artists, gallerists, collectors, art lovers and curators will gather to get to know the best of the work of Latin American creators.

As part of the curatorial proposal of Pinta Miami 2023, there are five Special Projects to honor different artistic identities.

SPECIAL PROJECTS: DIFFERENT ARTISTIC IDENTITIES AT PINTA MIAMI 2023

As part of the curatorial proposal of Pinta Miami 2023, there are five Special Projects to honor different artistic identities.

Pinta Miami 2023 closed its 17th edition celebrating Latin American art with artists, curators, collectors and a large number of visitors and art lovers.

PINTA MIAMI 2023 – A MEETING AND DIFFUSION EPICENTER

Pinta Miami 2023 closed its 17th edition celebrating Latin American art with artists, curators, collectors and a large number of visitors and art lovers.

Independent Curators International (ICI) is now accepting applications for the 2024 Curatorial Research Fellowships.

CALL FOR APPLICATIONS: CURATORIAL RESEARCH FELLOWSHIPS

Independent Curators International (ICI) is now accepting applications for the 2024 Curatorial Research Fellowships.

La Otra Verdad (The Other Truth), the most recent individual exhibition of the artist Harry Chavez, is presented at the Ricardo Palma Cultural Center.

THE HYPNOTIC CREATURES OF HARRY CHAVEZ

La Otra Verdad (The Other Truth), the most recent individual exhibition of the artist Harry Chavez, is presented at the Ricardo Palma Cultural Center.

The Museo de Arte de Lima (MALI) and proyectoamil present Evoking a Space Beyond Cinema, the first monographic museum exhibition by Rosa Barba in Peru.

EVOKING A SPACE BEYOND CINEMA: ROSA BARBA IN PERU

The Museo de Arte de Lima (MALI) and proyectoamil present Evoking a Space Beyond Cinema, the first monographic museum exhibition by Rosa Barba in Peru.

Pinta PArC returns with a new edition: from April 24 to 28 at Casa Prado Miraflores, the fair will present an experimental and ambitious program, along with a careful selection of galleries.

PINTA PArC 2024 REAFFIRMS ITS COMMITMENT TO DISSEMINATE THE REGION'S ARTISTIC IDENTITIES

Pinta PArC returns with a new edition: from April 24 to 28 at Casa Prado Miraflores, the fair will present an experimental and ambitious program, along with a careful selection of galleries.