ANTONIO BRICEÑO REFLECTS ON THE VULNERABILITY AND SPLENDOR OF INDIGENOUS CULTURES

Born in Venezuela, Antonio Briceño is a photographer and biologist. His series Dioses de América. Panteón natural (Gods of America. Natural Pantheon) participates in the Special Project Amazonia of Pinta Miami 2023. He has been working for more than 20 years on this series, whose purpose is to make visible the indigenous mythologies that have survived Christianity and colonialism, but are still in danger of extinction.

The field work has led Briceño to know more than thirty-five native cultures of the five continents, guided by anthropological texts and advised by wise men, teachers and shamans. The series Dioses de América represented Venezuela at the 52nd Venice Biennial (2007) and has also been exhibited in Finland, France, Hungary, Sweden, Germany, England, Spain, the United States, Mexico, Colombia, New Zealand, Panama and Venezuela. He received the Green Leaf Award for Artistic Excellence 2008, awarded by the Natural World Museum and the UN.

In addition to your training in Digital Arts, you have a degree in Biology, what does this scientific knowledge contribute to the process of your work?

My training as a biologist manifests itself in several ways. First, the way I formulate and develop my projects has a scientific structure. It starts with a concern that leads to bibliographic research and the proposal of hypotheses in the form of sketches and preliminary schemes. This is followed by field work, in which I develop the basic photographic or videographic stage, which I later edit in my workshop. The way I organize and present my series also has a structure inherited from science.

On the other hand, the elements, phenomena and natural processes, ecosystems, living beings (including humans, of course), their situation of vulnerability and their relationships are the basis of my concerns and, therefore, of my work. We can say that science is the basis of my inspiration and provides the raw material and methods that shape the development of my work.

You are participating in the Special Project Amazonia of Pinta Miami 2023 with works from the series Dioses de América. Panteón natural. How does your visual language avoid victimization, on the one hand, and exoticism, on the other?

Throughout the development of my work, I started perceiving that any identity trait that does not correspond to the Western hegemonic culture ends up being labeled as "exotic". This is a rhetorical tool to execute racism and the superiority complex of the dominant culture in a way that is intended to be subtle and disguised. So, a character from Western culture, in a Western context and displaying all the Western fashions and customs in their splendor is perceived as "normal" and acceptable. But a character belonging to another culture (to any of the thousands of other possibilities of seeing the world from human eyes), if shown in its splendor, in its context, is immediately excluded as "exotic". Everything must revolve around the West. So different people and cultures are only allowed to enter the scene if they are shown with sarcasm, irony and shown as inferior: victims, misfits, pariahs on the verge of extinction.

-

Antonio Briceño. Rató. Spirit of the waters and waterfalls. Pemón Culture (2005).

-

Antonio Briceño. Rató. Spirit of the waters and waterfalls. Pemón Culture (2005).

The intention of my series Dioses de América is, on one hand, to propose graphic images for mythological characters of indigenous, ancestral cultures, as a support for the teachers in the schools of the communities where I work. But, above all, to show them to the rest of the Latin American –and world– population that knows much more about Greek and Roman mythologies –extinct millennia ago– and is completely unaware of the great mythologies of the civilizations of the continent that not only precede the culture that was imposed, but that still coexist around us, many of them maintaining their traditions and cosmogonic myths. I preferred to be loyal to the people with whom I work, to be coherent and reflect what for them is an ideal of beauty and majesty, since, after all, it is their gods and mythical beings that I am representing, precisely as an alternative to a culture blind to itself, which only shows and values a supposed superiority based on consumption, conquest and the imposition of its values.

I have never been interested in this position of showing the otherness as a victim, because I have learned and seen magnificent things that changed my life by living with these marginalized and plundered cultures, without plundering and ruin being the reason why I work with them, but rather, their wisdom, their relationship with nature and the rest of the Cosmos and their very rich representations of what we call the "collective unconscious".

-

Antonio Briceño. Ianambó. (Carmen Hortensia Subín). La persona: El Ikhará y tres Pumethó. Cultura Pumé, Venezuela, 2017.

-

Antonio Briceño. Ianambó. (Carmen Hortensia Subín). La persona: El Ikhará y tres Pumethó. Cultura Pumé, Venezuela, 2017.

-

Antonio Briceño. Iticiaí. (Julio Flores). El Yaguar. Cultura Pumé, Venezuela, 2017.

In your writings you describe how discovering that your great-grandmother was indigenous awakened in you an urgency to investigate indigenous cultures and prevent their disappearance. How can you awaken such curiosity and appreciation in an audience that has no such family or direct ties? In a region marked by imperialism and immigration, how much do we share with the cultures that surrounded us and still do?

From my point of view, what this knowledge of my ancestors did was to awaken in me the feeling of having a duty, a mission.

But curiosity for otherness, for other visions and dreams, does not depend on belonging to one group or another. It does not depend on our genes, nor even on our culture. The interest for the whole of humanity, for the infinite heritage we have as a species, should be a universal vocation, which would allow us all to feel a great fascination for seeing things from the countless points of view we have generated as a species (we are 8,000,000,000,000 people!).

Unfortunately, also as a species, we have the vocation to see only our navel and pretend that reason is the exclusive patrimony of the group to which we belong and that everything else is wrong. This limitation has not only given rise to the persecution and destruction of indigenous cultures, to the obsession to see everything different as exotic, but is the basis of our permanent state of war and destruction, and may also constitute our end and the end of thousands of other species...

-

Antonio Briceño. Rató III (Roberto Rodríguez)

Espíritu de las aguas y cascadas. Cultura Pemón, Venezuela, 2004.

-

Antonio Briceño. Iboribó. (Mauricio Rodríguez). Niño-Dios de los peces, cultura Pemón. 2003.

-

Antonio Briceño. Rató III (Roberto Rodríguez)

Espíritu de las aguas y cascadas. Cultura Pemón, Venezuela, 2004.

Your work in Dioses de América. Panteón natural presents an almost taxonomic characteristic of cultural elements, how do reason and emotion relate to the process and the results?

For the construction of this pantheon of nature I must conduct research on myths that is, effectively, taxonomic.

All indigenous cosmogonies are based on a millenary knowledge of nature, its components, relationships and flows. There is a logic that starts from this complete knowledge and transforms it into metaphors that speak of ourselves. This is the basis of the "archetypes" as a possibility of projecting outside what is inside, giving order and meaning to the world and to existence. Thus, the Earth is usually the Mother, because all resources come from her, because she sustains everyone. Or the Sky is usually the Father, because it generates and fertilizes the Earth, and because it is associated more with time than with space. Fire, as a symbol of culture, is usually stolen in mythologies, as a sign of the great difficulty that man faces to survive in such an imposing nature and to highlight the cost that culture has in separating us from the rest of the beings that, in reality, are siblings. All mythology has a rational basis based on the knowledge of nature and its relationships.

But human beings are not only reason, we are also emotion. And that is where beauty comes in, which concerns the body and not the mind. That is where poetry comes in, the possibility of transcending the basal logic and turning it into the source of the spirit.

The next step of knowing the greatness and complexity of the Cosmos is astonishment, and this astonishment gives rise to what we call Beauty, which has no words ("The rose is without why"). Beauty, emotion, is an emancipation of the spirit, which manages to free itself from the limits posed by reason. That is why in my work it is so important that, when talking about these great characters, after transmitting the myth on which they are based, it is beauty and magnificence that allows the viewer to fly or prostrate himself before the unusual. An epiphany.

In the almost 25 years that you have been working on this series, is there any event or discovery that has left a special mark on you? How has this mission impacted your way of perceiving life?

There have been so many discoveries that it is impossible to list or mention them separately. Every group I have worked with has made a change in me.

Each new vision, each new perspective, dazzles me, not only because of how wonderful diversity is in itself, but also because it is through the others that one can get to know oneself and become aware of oneself. Contrast is a mirror that highlights what has always been taken for granted. It cuts out what, because it was obvious, was invisible. It confronts us, makes us doubt our certainties. So, although it is true that I have learned many fascinating and new things for me, I have been dazzled by ancestral knowledge and techniques, I have changed many times my way of perceiving nature and, what I value most is that, thanks to these soul encounters, I have learned a little more to know myself. To discover and recreate my own myth.

Related Topics

May interest you

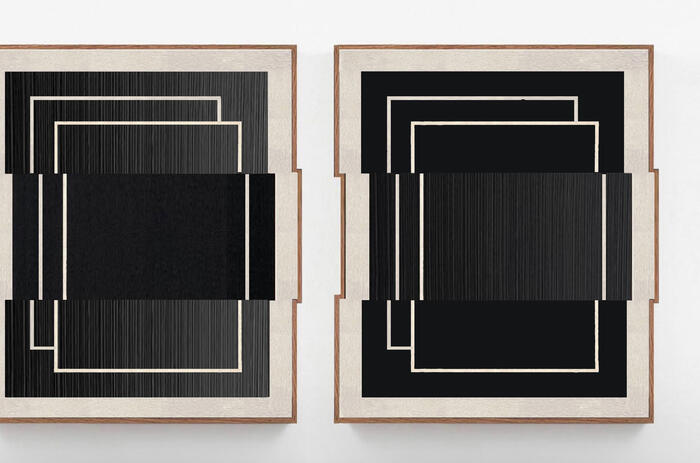

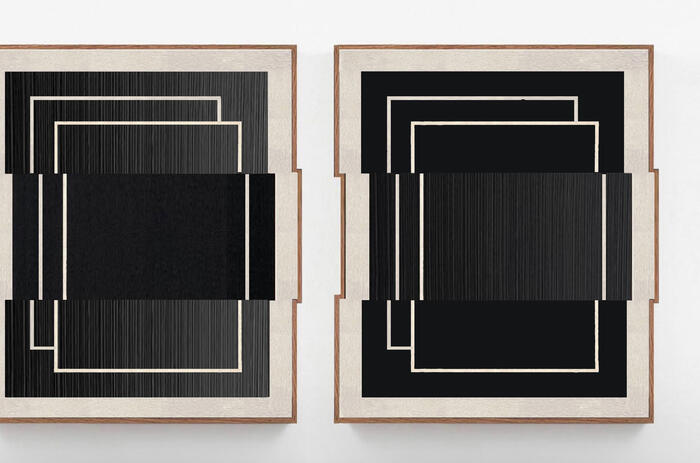

To celebrate the proyect’s 10-year-anniversary, the exhibition Piero Atchugarry Gallery: 10 years features the gallery’s represented artists from 13 countries.

PIERO ATCHUGARRY GALLERY CELEBRATES 10TH ANIVERSARY

To celebrate the proyect’s 10-year-anniversary, the exhibition Piero Atchugarry Gallery: 10 years features the gallery’s represented artists from 13 countries.

PIERO ATCHUGARRY GALLERY CELEBRATES 10TH ANIVERSARY

Diana Lowenstein gallery presents Time, Udo Nöger’s solo exhibition. In his latest works the artist advances his ongoing exploration of light and form.

Marquez Art Projects presents Cusp, a new body of work by José Delgado Zuñiga. In dynamic paintings and drawings that explode with surreal, humorous and intensely personal images, Zuñiga reflects the complexities of Chicano experiences, with a focus on the formation of identity and freedom.

JOSÉ DELGADO ZUÑIGA’S SOLO EXHIBITION AT MAP

Marquez Art Projects presents Cusp, a new body of work by José Delgado Zuñiga. In dynamic paintings and drawings that explode with surreal, humorous and intensely personal images, Zuñiga reflects the complexities of Chicano experiences, with a focus on the formation of identity and freedom.

Giuliana Vidarte is a curator, art historian and teacher. Her work focuses on the rewriting of history from the perspective of the discourse of the Peruvian Amazon. In an interview with Arte al Día, she talks about her career and how she developed the curatorial proposal for the NEXT section for Pinta Miami 2023.

GIULIANA VIDARTE: "THROUGH EXHIBITIONS WE CAN LOOK AT THE PAST IN ORDER TO THINK ABOUT TODAY"

Giuliana Vidarte is a curator, art historian and teacher. Her work focuses on the rewriting of history from the perspective of the discourse of the Peruvian Amazon. In an interview with Arte al Día, she talks about her career and how she developed the curatorial proposal for the NEXT section for Pinta Miami 2023.

Vibración Pura (Pure Vibration) is Jesús Rafael Soto’s solo exhibition at Ascaso Gallery.

PURE VIBRATIONS. SOTO’S 100TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATIONS

The Bass presents Hernan Bas: The Conceptualists, an exhibition on-view beginning December 4, 2023 that explores conceptual art as a permissive realm for creative behavior and an inviting space for queerness.

The Buenos Aires-based gallery Futbolitis is teaming up with (RE)BOOT, a new brand championing sustainability through sport, to present Tiempo Extra (Extra Time), an exhibition at Miami Design District.

ICA Miami presents the first solo museum presentation for New York–based artist Sasha Gordon, Surrogate Self. The surreal paintings and drawings that Gordon creates explore the complexities of bodily experience in gorgeous and hyper-realistic detail.

SASHA GORDON’S SURREAL SCENES AT ICA MIAMI

ICA Miami presents the first solo museum presentation for New York–based artist Sasha Gordon, Surrogate Self. The surreal paintings and drawings that Gordon creates explore the complexities of bodily experience in gorgeous and hyper-realistic detail.

Since the D+C Foundation’s Residency Program started –in 2022–, mid-career artists such as Sandra Monterroso, Jeronimo Villa, Guillermo García Cruz, Youdhisthir Maharjan and Loris Cecchini participated. The 2024 selected residents will be announced soon.

D+C FOUNDATION ARTISTS-IN-RESIDENCE PROGRAM

Since the D+C Foundation’s Residency Program started –in 2022–, mid-career artists such as Sandra Monterroso, Jeronimo Villa, Guillermo García Cruz, Youdhisthir Maharjan and Loris Cecchini participated. The 2024 selected residents will be announced soon.

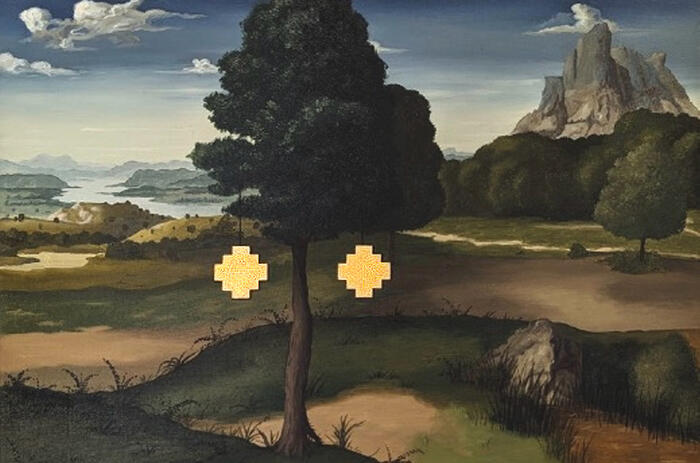

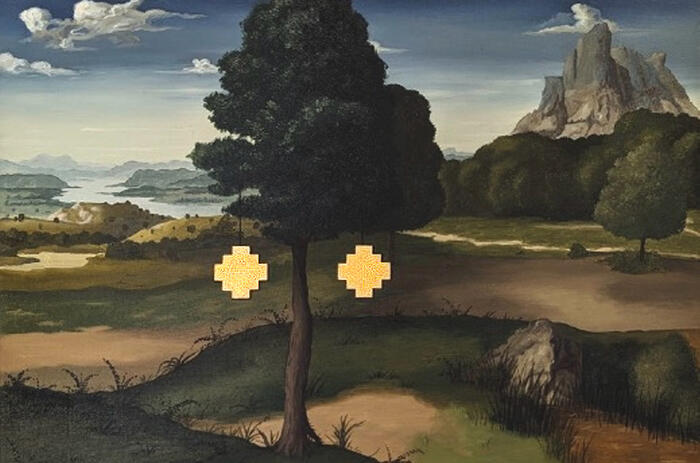

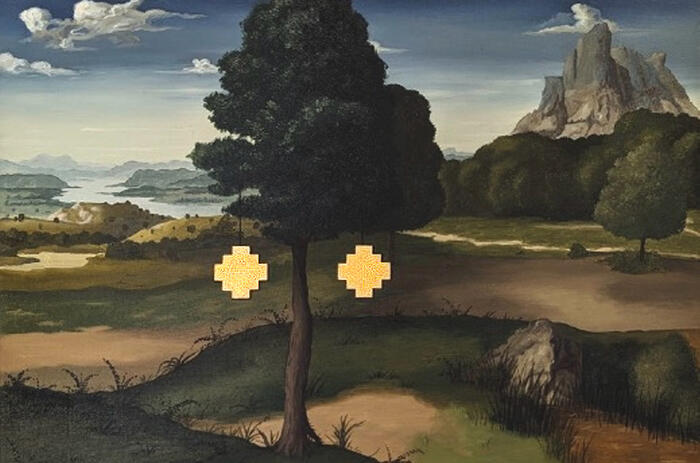

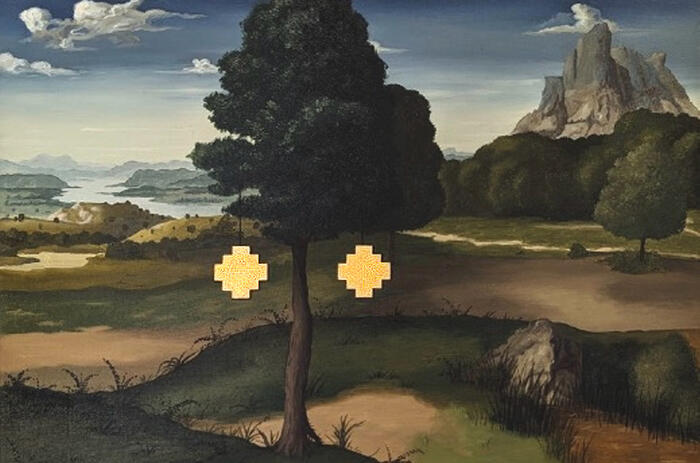

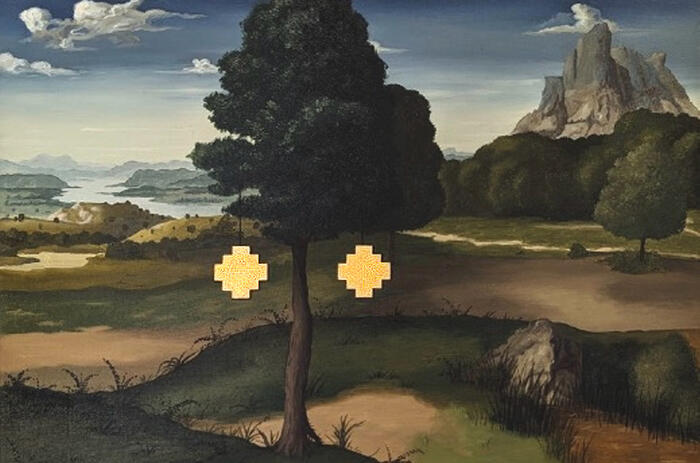

ROSAS Ek Balam gallery, based in Buenos Aires, presents works by Vicente Grondona and Max Gómez Canle in the RADAR section of Pinta Miami. Entitled Épica del paisaje (Epic of Landscape), this exhibition invokes the fragmentation of reality.

INFINITE REALITIES OF GRONDONA AND GÓMEZ CANLE ON PINTA'S RADAR

ROSAS Ek Balam gallery, based in Buenos Aires, presents works by Vicente Grondona and Max Gómez Canle in the RADAR section of Pinta Miami. Entitled Épica del paisaje (Epic of Landscape), this exhibition invokes the fragmentation of reality.

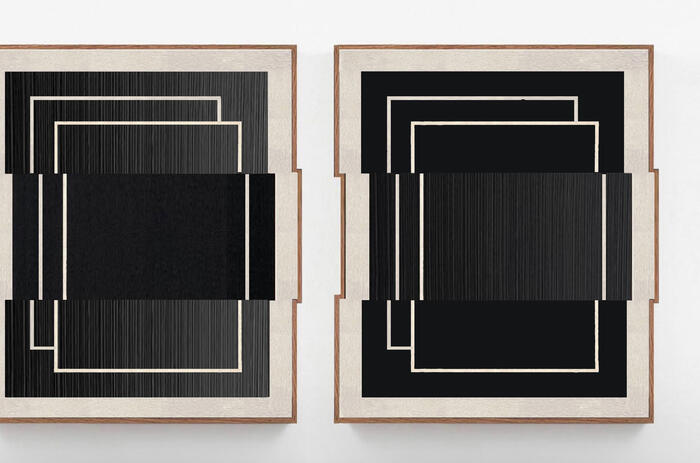

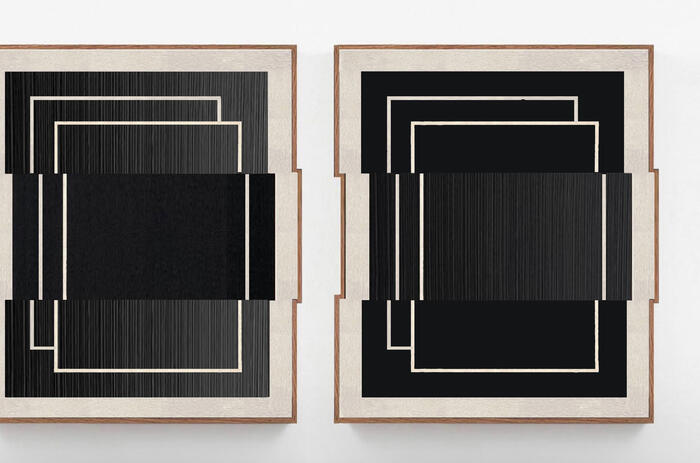

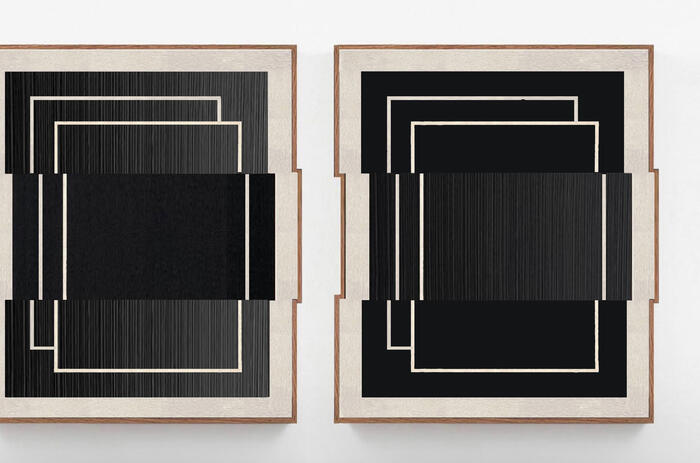

In her practice, Brazilian artist Manoela Medeiros questions artistic media by going beyond their conventional formats, producing paintings and in situ installations that explore the relationships between space, time, and the corporeality of art and of the viewer. Together with Felipe Cohen, they are part of Kubik Gallery’s proposal for Pinta Miami 2023.

MANOELA MEDEIROS ESCAPES ARTISTIC DEFINITIONS AND EXPLORES THE EVOLUTION OF THE NON-PLACE

In her practice, Brazilian artist Manoela Medeiros questions artistic media by going beyond their conventional formats, producing paintings and in situ installations that explore the relationships between space, time, and the corporeality of art and of the viewer. Together with Felipe Cohen, they are part of Kubik Gallery’s proposal for Pinta Miami 2023.

Rubell Museum is presenting three exhibitions: Basil Kincaid: Spirit in the Gift; Alejandro Piñeiro Bello; and Singular Views: Los Angeles.

Argentine artist Trinidad Metz Brea is part of the 2023 edition of Pinta Miami, within the NEXT section that presents emerging artists from Latin America. In an interview with Arte al Día, she explores the contradictions and challenges of our present and how this is the seedbed for her sculptures, murals and post-human figures.

POST-HUMANISM AND COLLABORATION. AN INTERVIEW WITH TRINIDAD METZ BREA

Argentine artist Trinidad Metz Brea is part of the 2023 edition of Pinta Miami, within the NEXT section that presents emerging artists from Latin America. In an interview with Arte al Día, she explores the contradictions and challenges of our present and how this is the seedbed for her sculptures, murals and post-human figures.

Until December 10, 2023, the 17th edition of Pinta Miami will be held at The Hangar in Coconut Grove. Artists, gallerists, collectors, art lovers and curators will gather to get to know the best of the work of Latin American creators.

THE LATIN AMERICAN IMAGINARIUM IN PINTA MIAMI 2023

Until December 10, 2023, the 17th edition of Pinta Miami will be held at The Hangar in Coconut Grove. Artists, gallerists, collectors, art lovers and curators will gather to get to know the best of the work of Latin American creators.

As part of the curatorial proposal of Pinta Miami 2023, there are five Special Projects to honor different artistic identities.

SPECIAL PROJECTS: DIFFERENT ARTISTIC IDENTITIES AT PINTA MIAMI 2023

As part of the curatorial proposal of Pinta Miami 2023, there are five Special Projects to honor different artistic identities.

Pinta Miami 2023 closed its 17th edition celebrating Latin American art with artists, curators, collectors and a large number of visitors and art lovers.

PINTA MIAMI 2023 – A MEETING AND DIFFUSION EPICENTER

Pinta Miami 2023 closed its 17th edition celebrating Latin American art with artists, curators, collectors and a large number of visitors and art lovers.

With the intention of rethinking the legacy of the Venezuelan-German artist Gego and its historical significance from the contemporary context, LA ESCUELA___ created a project of dialogue, learning and exchange Collective Reticulárea: Communal Cartographies.

COLLABORATIVE PROJECT IN HOMAGE TO GEGO

With the intention of rethinking the legacy of the Venezuelan-German artist Gego and its historical significance from the contemporary context, LA ESCUELA___ created a project of dialogue, learning and exchange Collective Reticulárea: Communal Cartographies.

Magdalena Fernández's Mobile Body Paintings arrived at the Clavijero Cultural Center, in Morelia, to breathe with the Mexican public.

THE MOBILE BODY PAINTINGS OF MAGDALENA FERNÁNDEZ

Magdalena Fernández's Mobile Body Paintings arrived at the Clavijero Cultural Center, in Morelia, to breathe with the Mexican public.

The VILLA in Fulda, Germany presents Action as Sculpture, an encounter between Lygia Clark and Franz Erhard Walther.

LYGIA CLARK AND FRANZ ERHARD WALTHER’S ARTISTIC EXPLORATION

The VILLA in Fulda, Germany presents Action as Sculpture, an encounter between Lygia Clark and Franz Erhard Walther.

Kunstinstituut Melly presented My Oma, a project that involves a group exhibition, concerts, performance, public programs and education activities. Conceptually interlaced throughout these formats are the figure of the grandmother, queries on ancestral knowledge, and ideas of cultural heritage.

CELEBRATING THE GRANDMOTHER AS A FIGURE OF KNOWLEDGE

Kunstinstituut Melly presented My Oma, a project that involves a group exhibition, concerts, performance, public programs and education activities. Conceptually interlaced throughout these formats are the figure of the grandmother, queries on ancestral knowledge, and ideas of cultural heritage.

To celebrate the proyect’s 10-year-anniversary, the exhibition Piero Atchugarry Gallery: 10 years features the gallery’s represented artists from 13 countries.

PIERO ATCHUGARRY GALLERY CELEBRATES 10TH ANIVERSARY

Diana Lowenstein gallery presents Time, Udo Nöger’s solo exhibition. In his latest works the artist advances his ongoing exploration of light and form.

Marquez Art Projects presents Cusp, a new body of work by José Delgado Zuñiga. In dynamic paintings and drawings that explode with surreal, humorous and intensely personal images, Zuñiga reflects the complexities of Chicano experiences, with a focus on the formation of identity and freedom.

JOSÉ DELGADO ZUÑIGA’S SOLO EXHIBITION AT MAP

Marquez Art Projects presents Cusp, a new body of work by José Delgado Zuñiga. In dynamic paintings and drawings that explode with surreal, humorous and intensely personal images, Zuñiga reflects the complexities of Chicano experiences, with a focus on the formation of identity and freedom.

Giuliana Vidarte is a curator, art historian and teacher. Her work focuses on the rewriting of history from the perspective of the discourse of the Peruvian Amazon. In an interview with Arte al Día, she talks about her career and how she developed the curatorial proposal for the NEXT section for Pinta Miami 2023.

GIULIANA VIDARTE: "THROUGH EXHIBITIONS WE CAN LOOK AT THE PAST IN ORDER TO THINK ABOUT TODAY"

Giuliana Vidarte is a curator, art historian and teacher. Her work focuses on the rewriting of history from the perspective of the discourse of the Peruvian Amazon. In an interview with Arte al Día, she talks about her career and how she developed the curatorial proposal for the NEXT section for Pinta Miami 2023.

Vibración Pura (Pure Vibration) is Jesús Rafael Soto’s solo exhibition at Ascaso Gallery.

PURE VIBRATIONS. SOTO’S 100TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATIONS

The Bass presents Hernan Bas: The Conceptualists, an exhibition on-view beginning December 4, 2023 that explores conceptual art as a permissive realm for creative behavior and an inviting space for queerness.

The Buenos Aires-based gallery Futbolitis is teaming up with (RE)BOOT, a new brand championing sustainability through sport, to present Tiempo Extra (Extra Time), an exhibition at Miami Design District.

ICA Miami presents the first solo museum presentation for New York–based artist Sasha Gordon, Surrogate Self. The surreal paintings and drawings that Gordon creates explore the complexities of bodily experience in gorgeous and hyper-realistic detail.

SASHA GORDON’S SURREAL SCENES AT ICA MIAMI

ICA Miami presents the first solo museum presentation for New York–based artist Sasha Gordon, Surrogate Self. The surreal paintings and drawings that Gordon creates explore the complexities of bodily experience in gorgeous and hyper-realistic detail.

Since the D+C Foundation’s Residency Program started –in 2022–, mid-career artists such as Sandra Monterroso, Jeronimo Villa, Guillermo García Cruz, Youdhisthir Maharjan and Loris Cecchini participated. The 2024 selected residents will be announced soon.

D+C FOUNDATION ARTISTS-IN-RESIDENCE PROGRAM

Since the D+C Foundation’s Residency Program started –in 2022–, mid-career artists such as Sandra Monterroso, Jeronimo Villa, Guillermo García Cruz, Youdhisthir Maharjan and Loris Cecchini participated. The 2024 selected residents will be announced soon.

ROSAS Ek Balam gallery, based in Buenos Aires, presents works by Vicente Grondona and Max Gómez Canle in the RADAR section of Pinta Miami. Entitled Épica del paisaje (Epic of Landscape), this exhibition invokes the fragmentation of reality.

INFINITE REALITIES OF GRONDONA AND GÓMEZ CANLE ON PINTA'S RADAR

ROSAS Ek Balam gallery, based in Buenos Aires, presents works by Vicente Grondona and Max Gómez Canle in the RADAR section of Pinta Miami. Entitled Épica del paisaje (Epic of Landscape), this exhibition invokes the fragmentation of reality.

In her practice, Brazilian artist Manoela Medeiros questions artistic media by going beyond their conventional formats, producing paintings and in situ installations that explore the relationships between space, time, and the corporeality of art and of the viewer. Together with Felipe Cohen, they are part of Kubik Gallery’s proposal for Pinta Miami 2023.

MANOELA MEDEIROS ESCAPES ARTISTIC DEFINITIONS AND EXPLORES THE EVOLUTION OF THE NON-PLACE

In her practice, Brazilian artist Manoela Medeiros questions artistic media by going beyond their conventional formats, producing paintings and in situ installations that explore the relationships between space, time, and the corporeality of art and of the viewer. Together with Felipe Cohen, they are part of Kubik Gallery’s proposal for Pinta Miami 2023.

Rubell Museum is presenting three exhibitions: Basil Kincaid: Spirit in the Gift; Alejandro Piñeiro Bello; and Singular Views: Los Angeles.

Argentine artist Trinidad Metz Brea is part of the 2023 edition of Pinta Miami, within the NEXT section that presents emerging artists from Latin America. In an interview with Arte al Día, she explores the contradictions and challenges of our present and how this is the seedbed for her sculptures, murals and post-human figures.

POST-HUMANISM AND COLLABORATION. AN INTERVIEW WITH TRINIDAD METZ BREA

Argentine artist Trinidad Metz Brea is part of the 2023 edition of Pinta Miami, within the NEXT section that presents emerging artists from Latin America. In an interview with Arte al Día, she explores the contradictions and challenges of our present and how this is the seedbed for her sculptures, murals and post-human figures.

Until December 10, 2023, the 17th edition of Pinta Miami will be held at The Hangar in Coconut Grove. Artists, gallerists, collectors, art lovers and curators will gather to get to know the best of the work of Latin American creators.

THE LATIN AMERICAN IMAGINARIUM IN PINTA MIAMI 2023

Until December 10, 2023, the 17th edition of Pinta Miami will be held at The Hangar in Coconut Grove. Artists, gallerists, collectors, art lovers and curators will gather to get to know the best of the work of Latin American creators.

As part of the curatorial proposal of Pinta Miami 2023, there are five Special Projects to honor different artistic identities.

SPECIAL PROJECTS: DIFFERENT ARTISTIC IDENTITIES AT PINTA MIAMI 2023

As part of the curatorial proposal of Pinta Miami 2023, there are five Special Projects to honor different artistic identities.

Pinta Miami 2023 closed its 17th edition celebrating Latin American art with artists, curators, collectors and a large number of visitors and art lovers.

PINTA MIAMI 2023 – A MEETING AND DIFFUSION EPICENTER

Pinta Miami 2023 closed its 17th edition celebrating Latin American art with artists, curators, collectors and a large number of visitors and art lovers.

With the intention of rethinking the legacy of the Venezuelan-German artist Gego and its historical significance from the contemporary context, LA ESCUELA___ created a project of dialogue, learning and exchange Collective Reticulárea: Communal Cartographies.

COLLABORATIVE PROJECT IN HOMAGE TO GEGO

With the intention of rethinking the legacy of the Venezuelan-German artist Gego and its historical significance from the contemporary context, LA ESCUELA___ created a project of dialogue, learning and exchange Collective Reticulárea: Communal Cartographies.

Magdalena Fernández's Mobile Body Paintings arrived at the Clavijero Cultural Center, in Morelia, to breathe with the Mexican public.

THE MOBILE BODY PAINTINGS OF MAGDALENA FERNÁNDEZ

Magdalena Fernández's Mobile Body Paintings arrived at the Clavijero Cultural Center, in Morelia, to breathe with the Mexican public.

The VILLA in Fulda, Germany presents Action as Sculpture, an encounter between Lygia Clark and Franz Erhard Walther.

LYGIA CLARK AND FRANZ ERHARD WALTHER’S ARTISTIC EXPLORATION

The VILLA in Fulda, Germany presents Action as Sculpture, an encounter between Lygia Clark and Franz Erhard Walther.

Kunstinstituut Melly presented My Oma, a project that involves a group exhibition, concerts, performance, public programs and education activities. Conceptually interlaced throughout these formats are the figure of the grandmother, queries on ancestral knowledge, and ideas of cultural heritage.

CELEBRATING THE GRANDMOTHER AS A FIGURE OF KNOWLEDGE

Kunstinstituut Melly presented My Oma, a project that involves a group exhibition, concerts, performance, public programs and education activities. Conceptually interlaced throughout these formats are the figure of the grandmother, queries on ancestral knowledge, and ideas of cultural heritage.

To celebrate the proyect’s 10-year-anniversary, the exhibition Piero Atchugarry Gallery: 10 years features the gallery’s represented artists from 13 countries.

PIERO ATCHUGARRY GALLERY CELEBRATES 10TH ANIVERSARY

Diana Lowenstein gallery presents Time, Udo Nöger’s solo exhibition. In his latest works the artist advances his ongoing exploration of light and form.

Marquez Art Projects presents Cusp, a new body of work by José Delgado Zuñiga. In dynamic paintings and drawings that explode with surreal, humorous and intensely personal images, Zuñiga reflects the complexities of Chicano experiences, with a focus on the formation of identity and freedom.

JOSÉ DELGADO ZUÑIGA’S SOLO EXHIBITION AT MAP

Marquez Art Projects presents Cusp, a new body of work by José Delgado Zuñiga. In dynamic paintings and drawings that explode with surreal, humorous and intensely personal images, Zuñiga reflects the complexities of Chicano experiences, with a focus on the formation of identity and freedom.

Giuliana Vidarte is a curator, art historian and teacher. Her work focuses on the rewriting of history from the perspective of the discourse of the Peruvian Amazon. In an interview with Arte al Día, she talks about her career and how she developed the curatorial proposal for the NEXT section for Pinta Miami 2023.

GIULIANA VIDARTE: "THROUGH EXHIBITIONS WE CAN LOOK AT THE PAST IN ORDER TO THINK ABOUT TODAY"

Giuliana Vidarte is a curator, art historian and teacher. Her work focuses on the rewriting of history from the perspective of the discourse of the Peruvian Amazon. In an interview with Arte al Día, she talks about her career and how she developed the curatorial proposal for the NEXT section for Pinta Miami 2023.

Vibración Pura (Pure Vibration) is Jesús Rafael Soto’s solo exhibition at Ascaso Gallery.

PURE VIBRATIONS. SOTO’S 100TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATIONS

The Bass presents Hernan Bas: The Conceptualists, an exhibition on-view beginning December 4, 2023 that explores conceptual art as a permissive realm for creative behavior and an inviting space for queerness.

The Buenos Aires-based gallery Futbolitis is teaming up with (RE)BOOT, a new brand championing sustainability through sport, to present Tiempo Extra (Extra Time), an exhibition at Miami Design District.

ICA Miami presents the first solo museum presentation for New York–based artist Sasha Gordon, Surrogate Self. The surreal paintings and drawings that Gordon creates explore the complexities of bodily experience in gorgeous and hyper-realistic detail.

SASHA GORDON’S SURREAL SCENES AT ICA MIAMI

ICA Miami presents the first solo museum presentation for New York–based artist Sasha Gordon, Surrogate Self. The surreal paintings and drawings that Gordon creates explore the complexities of bodily experience in gorgeous and hyper-realistic detail.

Since the D+C Foundation’s Residency Program started –in 2022–, mid-career artists such as Sandra Monterroso, Jeronimo Villa, Guillermo García Cruz, Youdhisthir Maharjan and Loris Cecchini participated. The 2024 selected residents will be announced soon.

D+C FOUNDATION ARTISTS-IN-RESIDENCE PROGRAM

Since the D+C Foundation’s Residency Program started –in 2022–, mid-career artists such as Sandra Monterroso, Jeronimo Villa, Guillermo García Cruz, Youdhisthir Maharjan and Loris Cecchini participated. The 2024 selected residents will be announced soon.

ROSAS Ek Balam gallery, based in Buenos Aires, presents works by Vicente Grondona and Max Gómez Canle in the RADAR section of Pinta Miami. Entitled Épica del paisaje (Epic of Landscape), this exhibition invokes the fragmentation of reality.

INFINITE REALITIES OF GRONDONA AND GÓMEZ CANLE ON PINTA'S RADAR

ROSAS Ek Balam gallery, based in Buenos Aires, presents works by Vicente Grondona and Max Gómez Canle in the RADAR section of Pinta Miami. Entitled Épica del paisaje (Epic of Landscape), this exhibition invokes the fragmentation of reality.

In her practice, Brazilian artist Manoela Medeiros questions artistic media by going beyond their conventional formats, producing paintings and in situ installations that explore the relationships between space, time, and the corporeality of art and of the viewer. Together with Felipe Cohen, they are part of Kubik Gallery’s proposal for Pinta Miami 2023.

MANOELA MEDEIROS ESCAPES ARTISTIC DEFINITIONS AND EXPLORES THE EVOLUTION OF THE NON-PLACE

In her practice, Brazilian artist Manoela Medeiros questions artistic media by going beyond their conventional formats, producing paintings and in situ installations that explore the relationships between space, time, and the corporeality of art and of the viewer. Together with Felipe Cohen, they are part of Kubik Gallery’s proposal for Pinta Miami 2023.

Rubell Museum is presenting three exhibitions: Basil Kincaid: Spirit in the Gift; Alejandro Piñeiro Bello; and Singular Views: Los Angeles.

Argentine artist Trinidad Metz Brea is part of the 2023 edition of Pinta Miami, within the NEXT section that presents emerging artists from Latin America. In an interview with Arte al Día, she explores the contradictions and challenges of our present and how this is the seedbed for her sculptures, murals and post-human figures.

POST-HUMANISM AND COLLABORATION. AN INTERVIEW WITH TRINIDAD METZ BREA

Argentine artist Trinidad Metz Brea is part of the 2023 edition of Pinta Miami, within the NEXT section that presents emerging artists from Latin America. In an interview with Arte al Día, she explores the contradictions and challenges of our present and how this is the seedbed for her sculptures, murals and post-human figures.

Until December 10, 2023, the 17th edition of Pinta Miami will be held at The Hangar in Coconut Grove. Artists, gallerists, collectors, art lovers and curators will gather to get to know the best of the work of Latin American creators.

THE LATIN AMERICAN IMAGINARIUM IN PINTA MIAMI 2023

Until December 10, 2023, the 17th edition of Pinta Miami will be held at The Hangar in Coconut Grove. Artists, gallerists, collectors, art lovers and curators will gather to get to know the best of the work of Latin American creators.

As part of the curatorial proposal of Pinta Miami 2023, there are five Special Projects to honor different artistic identities.

SPECIAL PROJECTS: DIFFERENT ARTISTIC IDENTITIES AT PINTA MIAMI 2023

As part of the curatorial proposal of Pinta Miami 2023, there are five Special Projects to honor different artistic identities.

Pinta Miami 2023 closed its 17th edition celebrating Latin American art with artists, curators, collectors and a large number of visitors and art lovers.

PINTA MIAMI 2023 – A MEETING AND DIFFUSION EPICENTER

Pinta Miami 2023 closed its 17th edition celebrating Latin American art with artists, curators, collectors and a large number of visitors and art lovers.

With the intention of rethinking the legacy of the Venezuelan-German artist Gego and its historical significance from the contemporary context, LA ESCUELA___ created a project of dialogue, learning and exchange Collective Reticulárea: Communal Cartographies.

COLLABORATIVE PROJECT IN HOMAGE TO GEGO

With the intention of rethinking the legacy of the Venezuelan-German artist Gego and its historical significance from the contemporary context, LA ESCUELA___ created a project of dialogue, learning and exchange Collective Reticulárea: Communal Cartographies.

Magdalena Fernández's Mobile Body Paintings arrived at the Clavijero Cultural Center, in Morelia, to breathe with the Mexican public.

THE MOBILE BODY PAINTINGS OF MAGDALENA FERNÁNDEZ

Magdalena Fernández's Mobile Body Paintings arrived at the Clavijero Cultural Center, in Morelia, to breathe with the Mexican public.

The VILLA in Fulda, Germany presents Action as Sculpture, an encounter between Lygia Clark and Franz Erhard Walther.

LYGIA CLARK AND FRANZ ERHARD WALTHER’S ARTISTIC EXPLORATION

The VILLA in Fulda, Germany presents Action as Sculpture, an encounter between Lygia Clark and Franz Erhard Walther.

Kunstinstituut Melly presented My Oma, a project that involves a group exhibition, concerts, performance, public programs and education activities. Conceptually interlaced throughout these formats are the figure of the grandmother, queries on ancestral knowledge, and ideas of cultural heritage.

CELEBRATING THE GRANDMOTHER AS A FIGURE OF KNOWLEDGE

Kunstinstituut Melly presented My Oma, a project that involves a group exhibition, concerts, performance, public programs and education activities. Conceptually interlaced throughout these formats are the figure of the grandmother, queries on ancestral knowledge, and ideas of cultural heritage.

To celebrate the proyect’s 10-year-anniversary, the exhibition Piero Atchugarry Gallery: 10 years features the gallery’s represented artists from 13 countries.

PIERO ATCHUGARRY GALLERY CELEBRATES 10TH ANIVERSARY

Diana Lowenstein gallery presents Time, Udo Nöger’s solo exhibition. In his latest works the artist advances his ongoing exploration of light and form.

Marquez Art Projects presents Cusp, a new body of work by José Delgado Zuñiga. In dynamic paintings and drawings that explode with surreal, humorous and intensely personal images, Zuñiga reflects the complexities of Chicano experiences, with a focus on the formation of identity and freedom.

JOSÉ DELGADO ZUÑIGA’S SOLO EXHIBITION AT MAP

Marquez Art Projects presents Cusp, a new body of work by José Delgado Zuñiga. In dynamic paintings and drawings that explode with surreal, humorous and intensely personal images, Zuñiga reflects the complexities of Chicano experiences, with a focus on the formation of identity and freedom.

Giuliana Vidarte is a curator, art historian and teacher. Her work focuses on the rewriting of history from the perspective of the discourse of the Peruvian Amazon. In an interview with Arte al Día, she talks about her career and how she developed the curatorial proposal for the NEXT section for Pinta Miami 2023.

GIULIANA VIDARTE: "THROUGH EXHIBITIONS WE CAN LOOK AT THE PAST IN ORDER TO THINK ABOUT TODAY"

Giuliana Vidarte is a curator, art historian and teacher. Her work focuses on the rewriting of history from the perspective of the discourse of the Peruvian Amazon. In an interview with Arte al Día, she talks about her career and how she developed the curatorial proposal for the NEXT section for Pinta Miami 2023.

Vibración Pura (Pure Vibration) is Jesús Rafael Soto’s solo exhibition at Ascaso Gallery.

PURE VIBRATIONS. SOTO’S 100TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATIONS

The Bass presents Hernan Bas: The Conceptualists, an exhibition on-view beginning December 4, 2023 that explores conceptual art as a permissive realm for creative behavior and an inviting space for queerness.

The Buenos Aires-based gallery Futbolitis is teaming up with (RE)BOOT, a new brand championing sustainability through sport, to present Tiempo Extra (Extra Time), an exhibition at Miami Design District.

ICA Miami presents the first solo museum presentation for New York–based artist Sasha Gordon, Surrogate Self. The surreal paintings and drawings that Gordon creates explore the complexities of bodily experience in gorgeous and hyper-realistic detail.

SASHA GORDON’S SURREAL SCENES AT ICA MIAMI

ICA Miami presents the first solo museum presentation for New York–based artist Sasha Gordon, Surrogate Self. The surreal paintings and drawings that Gordon creates explore the complexities of bodily experience in gorgeous and hyper-realistic detail.

Since the D+C Foundation’s Residency Program started –in 2022–, mid-career artists such as Sandra Monterroso, Jeronimo Villa, Guillermo García Cruz, Youdhisthir Maharjan and Loris Cecchini participated. The 2024 selected residents will be announced soon.

D+C FOUNDATION ARTISTS-IN-RESIDENCE PROGRAM

Since the D+C Foundation’s Residency Program started –in 2022–, mid-career artists such as Sandra Monterroso, Jeronimo Villa, Guillermo García Cruz, Youdhisthir Maharjan and Loris Cecchini participated. The 2024 selected residents will be announced soon.

ROSAS Ek Balam gallery, based in Buenos Aires, presents works by Vicente Grondona and Max Gómez Canle in the RADAR section of Pinta Miami. Entitled Épica del paisaje (Epic of Landscape), this exhibition invokes the fragmentation of reality.

INFINITE REALITIES OF GRONDONA AND GÓMEZ CANLE ON PINTA'S RADAR

ROSAS Ek Balam gallery, based in Buenos Aires, presents works by Vicente Grondona and Max Gómez Canle in the RADAR section of Pinta Miami. Entitled Épica del paisaje (Epic of Landscape), this exhibition invokes the fragmentation of reality.

In her practice, Brazilian artist Manoela Medeiros questions artistic media by going beyond their conventional formats, producing paintings and in situ installations that explore the relationships between space, time, and the corporeality of art and of the viewer. Together with Felipe Cohen, they are part of Kubik Gallery’s proposal for Pinta Miami 2023.

MANOELA MEDEIROS ESCAPES ARTISTIC DEFINITIONS AND EXPLORES THE EVOLUTION OF THE NON-PLACE

In her practice, Brazilian artist Manoela Medeiros questions artistic media by going beyond their conventional formats, producing paintings and in situ installations that explore the relationships between space, time, and the corporeality of art and of the viewer. Together with Felipe Cohen, they are part of Kubik Gallery’s proposal for Pinta Miami 2023.

Rubell Museum is presenting three exhibitions: Basil Kincaid: Spirit in the Gift; Alejandro Piñeiro Bello; and Singular Views: Los Angeles.

Argentine artist Trinidad Metz Brea is part of the 2023 edition of Pinta Miami, within the NEXT section that presents emerging artists from Latin America. In an interview with Arte al Día, she explores the contradictions and challenges of our present and how this is the seedbed for her sculptures, murals and post-human figures.

POST-HUMANISM AND COLLABORATION. AN INTERVIEW WITH TRINIDAD METZ BREA

Argentine artist Trinidad Metz Brea is part of the 2023 edition of Pinta Miami, within the NEXT section that presents emerging artists from Latin America. In an interview with Arte al Día, she explores the contradictions and challenges of our present and how this is the seedbed for her sculptures, murals and post-human figures.

Until December 10, 2023, the 17th edition of Pinta Miami will be held at The Hangar in Coconut Grove. Artists, gallerists, collectors, art lovers and curators will gather to get to know the best of the work of Latin American creators.

THE LATIN AMERICAN IMAGINARIUM IN PINTA MIAMI 2023

Until December 10, 2023, the 17th edition of Pinta Miami will be held at The Hangar in Coconut Grove. Artists, gallerists, collectors, art lovers and curators will gather to get to know the best of the work of Latin American creators.

As part of the curatorial proposal of Pinta Miami 2023, there are five Special Projects to honor different artistic identities.

SPECIAL PROJECTS: DIFFERENT ARTISTIC IDENTITIES AT PINTA MIAMI 2023

As part of the curatorial proposal of Pinta Miami 2023, there are five Special Projects to honor different artistic identities.

Pinta Miami 2023 closed its 17th edition celebrating Latin American art with artists, curators, collectors and a large number of visitors and art lovers.

PINTA MIAMI 2023 – A MEETING AND DIFFUSION EPICENTER

Pinta Miami 2023 closed its 17th edition celebrating Latin American art with artists, curators, collectors and a large number of visitors and art lovers.

With the intention of rethinking the legacy of the Venezuelan-German artist Gego and its historical significance from the contemporary context, LA ESCUELA___ created a project of dialogue, learning and exchange Collective Reticulárea: Communal Cartographies.

COLLABORATIVE PROJECT IN HOMAGE TO GEGO

With the intention of rethinking the legacy of the Venezuelan-German artist Gego and its historical significance from the contemporary context, LA ESCUELA___ created a project of dialogue, learning and exchange Collective Reticulárea: Communal Cartographies.

Magdalena Fernández's Mobile Body Paintings arrived at the Clavijero Cultural Center, in Morelia, to breathe with the Mexican public.

THE MOBILE BODY PAINTINGS OF MAGDALENA FERNÁNDEZ

Magdalena Fernández's Mobile Body Paintings arrived at the Clavijero Cultural Center, in Morelia, to breathe with the Mexican public.

The VILLA in Fulda, Germany presents Action as Sculpture, an encounter between Lygia Clark and Franz Erhard Walther.

LYGIA CLARK AND FRANZ ERHARD WALTHER’S ARTISTIC EXPLORATION

The VILLA in Fulda, Germany presents Action as Sculpture, an encounter between Lygia Clark and Franz Erhard Walther.

Kunstinstituut Melly presented My Oma, a project that involves a group exhibition, concerts, performance, public programs and education activities. Conceptually interlaced throughout these formats are the figure of the grandmother, queries on ancestral knowledge, and ideas of cultural heritage.

CELEBRATING THE GRANDMOTHER AS A FIGURE OF KNOWLEDGE

Kunstinstituut Melly presented My Oma, a project that involves a group exhibition, concerts, performance, public programs and education activities. Conceptually interlaced throughout these formats are the figure of the grandmother, queries on ancestral knowledge, and ideas of cultural heritage.

To celebrate the proyect’s 10-year-anniversary, the exhibition Piero Atchugarry Gallery: 10 years features the gallery’s represented artists from 13 countries.

PIERO ATCHUGARRY GALLERY CELEBRATES 10TH ANIVERSARY

Diana Lowenstein gallery presents Time, Udo Nöger’s solo exhibition. In his latest works the artist advances his ongoing exploration of light and form.

Marquez Art Projects presents Cusp, a new body of work by José Delgado Zuñiga. In dynamic paintings and drawings that explode with surreal, humorous and intensely personal images, Zuñiga reflects the complexities of Chicano experiences, with a focus on the formation of identity and freedom.

JOSÉ DELGADO ZUÑIGA’S SOLO EXHIBITION AT MAP

Marquez Art Projects presents Cusp, a new body of work by José Delgado Zuñiga. In dynamic paintings and drawings that explode with surreal, humorous and intensely personal images, Zuñiga reflects the complexities of Chicano experiences, with a focus on the formation of identity and freedom.

Giuliana Vidarte is a curator, art historian and teacher. Her work focuses on the rewriting of history from the perspective of the discourse of the Peruvian Amazon. In an interview with Arte al Día, she talks about her career and how she developed the curatorial proposal for the NEXT section for Pinta Miami 2023.

GIULIANA VIDARTE: "THROUGH EXHIBITIONS WE CAN LOOK AT THE PAST IN ORDER TO THINK ABOUT TODAY"

Giuliana Vidarte is a curator, art historian and teacher. Her work focuses on the rewriting of history from the perspective of the discourse of the Peruvian Amazon. In an interview with Arte al Día, she talks about her career and how she developed the curatorial proposal for the NEXT section for Pinta Miami 2023.

Vibración Pura (Pure Vibration) is Jesús Rafael Soto’s solo exhibition at Ascaso Gallery.

PURE VIBRATIONS. SOTO’S 100TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATIONS

The Bass presents Hernan Bas: The Conceptualists, an exhibition on-view beginning December 4, 2023 that explores conceptual art as a permissive realm for creative behavior and an inviting space for queerness.

The Buenos Aires-based gallery Futbolitis is teaming up with (RE)BOOT, a new brand championing sustainability through sport, to present Tiempo Extra (Extra Time), an exhibition at Miami Design District.

ICA Miami presents the first solo museum presentation for New York–based artist Sasha Gordon, Surrogate Self. The surreal paintings and drawings that Gordon creates explore the complexities of bodily experience in gorgeous and hyper-realistic detail.

SASHA GORDON’S SURREAL SCENES AT ICA MIAMI

ICA Miami presents the first solo museum presentation for New York–based artist Sasha Gordon, Surrogate Self. The surreal paintings and drawings that Gordon creates explore the complexities of bodily experience in gorgeous and hyper-realistic detail.

Since the D+C Foundation’s Residency Program started –in 2022–, mid-career artists such as Sandra Monterroso, Jeronimo Villa, Guillermo García Cruz, Youdhisthir Maharjan and Loris Cecchini participated. The 2024 selected residents will be announced soon.

D+C FOUNDATION ARTISTS-IN-RESIDENCE PROGRAM

Since the D+C Foundation’s Residency Program started –in 2022–, mid-career artists such as Sandra Monterroso, Jeronimo Villa, Guillermo García Cruz, Youdhisthir Maharjan and Loris Cecchini participated. The 2024 selected residents will be announced soon.

ROSAS Ek Balam gallery, based in Buenos Aires, presents works by Vicente Grondona and Max Gómez Canle in the RADAR section of Pinta Miami. Entitled Épica del paisaje (Epic of Landscape), this exhibition invokes the fragmentation of reality.

INFINITE REALITIES OF GRONDONA AND GÓMEZ CANLE ON PINTA'S RADAR

ROSAS Ek Balam gallery, based in Buenos Aires, presents works by Vicente Grondona and Max Gómez Canle in the RADAR section of Pinta Miami. Entitled Épica del paisaje (Epic of Landscape), this exhibition invokes the fragmentation of reality.

In her practice, Brazilian artist Manoela Medeiros questions artistic media by going beyond their conventional formats, producing paintings and in situ installations that explore the relationships between space, time, and the corporeality of art and of the viewer. Together with Felipe Cohen, they are part of Kubik Gallery’s proposal for Pinta Miami 2023.

MANOELA MEDEIROS ESCAPES ARTISTIC DEFINITIONS AND EXPLORES THE EVOLUTION OF THE NON-PLACE

In her practice, Brazilian artist Manoela Medeiros questions artistic media by going beyond their conventional formats, producing paintings and in situ installations that explore the relationships between space, time, and the corporeality of art and of the viewer. Together with Felipe Cohen, they are part of Kubik Gallery’s proposal for Pinta Miami 2023.

Rubell Museum is presenting three exhibitions: Basil Kincaid: Spirit in the Gift; Alejandro Piñeiro Bello; and Singular Views: Los Angeles.

Argentine artist Trinidad Metz Brea is part of the 2023 edition of Pinta Miami, within the NEXT section that presents emerging artists from Latin America. In an interview with Arte al Día, she explores the contradictions and challenges of our present and how this is the seedbed for her sculptures, murals and post-human figures.

POST-HUMANISM AND COLLABORATION. AN INTERVIEW WITH TRINIDAD METZ BREA

Argentine artist Trinidad Metz Brea is part of the 2023 edition of Pinta Miami, within the NEXT section that presents emerging artists from Latin America. In an interview with Arte al Día, she explores the contradictions and challenges of our present and how this is the seedbed for her sculptures, murals and post-human figures.

Until December 10, 2023, the 17th edition of Pinta Miami will be held at The Hangar in Coconut Grove. Artists, gallerists, collectors, art lovers and curators will gather to get to know the best of the work of Latin American creators.

THE LATIN AMERICAN IMAGINARIUM IN PINTA MIAMI 2023

Until December 10, 2023, the 17th edition of Pinta Miami will be held at The Hangar in Coconut Grove. Artists, gallerists, collectors, art lovers and curators will gather to get to know the best of the work of Latin American creators.

As part of the curatorial proposal of Pinta Miami 2023, there are five Special Projects to honor different artistic identities.

SPECIAL PROJECTS: DIFFERENT ARTISTIC IDENTITIES AT PINTA MIAMI 2023

As part of the curatorial proposal of Pinta Miami 2023, there are five Special Projects to honor different artistic identities.

Pinta Miami 2023 closed its 17th edition celebrating Latin American art with artists, curators, collectors and a large number of visitors and art lovers.

PINTA MIAMI 2023 – A MEETING AND DIFFUSION EPICENTER

Pinta Miami 2023 closed its 17th edition celebrating Latin American art with artists, curators, collectors and a large number of visitors and art lovers.

With the intention of rethinking the legacy of the Venezuelan-German artist Gego and its historical significance from the contemporary context, LA ESCUELA___ created a project of dialogue, learning and exchange Collective Reticulárea: Communal Cartographies.

COLLABORATIVE PROJECT IN HOMAGE TO GEGO

With the intention of rethinking the legacy of the Venezuelan-German artist Gego and its historical significance from the contemporary context, LA ESCUELA___ created a project of dialogue, learning and exchange Collective Reticulárea: Communal Cartographies.

Magdalena Fernández's Mobile Body Paintings arrived at the Clavijero Cultural Center, in Morelia, to breathe with the Mexican public.

THE MOBILE BODY PAINTINGS OF MAGDALENA FERNÁNDEZ

Magdalena Fernández's Mobile Body Paintings arrived at the Clavijero Cultural Center, in Morelia, to breathe with the Mexican public.

The VILLA in Fulda, Germany presents Action as Sculpture, an encounter between Lygia Clark and Franz Erhard Walther.

LYGIA CLARK AND FRANZ ERHARD WALTHER’S ARTISTIC EXPLORATION

The VILLA in Fulda, Germany presents Action as Sculpture, an encounter between Lygia Clark and Franz Erhard Walther.

Kunstinstituut Melly presented My Oma, a project that involves a group exhibition, concerts, performance, public programs and education activities. Conceptually interlaced throughout these formats are the figure of the grandmother, queries on ancestral knowledge, and ideas of cultural heritage.

CELEBRATING THE GRANDMOTHER AS A FIGURE OF KNOWLEDGE

Kunstinstituut Melly presented My Oma, a project that involves a group exhibition, concerts, performance, public programs and education activities. Conceptually interlaced throughout these formats are the figure of the grandmother, queries on ancestral knowledge, and ideas of cultural heritage.