LUCILA GRADIN: A JOURNEY THROUGH COLOR

Lucila Gradin begins her work when creating her own natural dyes –through dyeing and medicinal plants from all over the world– and culminates it by pursuing the image that leaves every trace of this ancestral practice through embroidery, textiles and compositions on paper. The Argentine artist is part of the RADAR section of Pinta PArC 2024, together with COTT Gallery.

What place does nature have in your process and journey?

I was born in Bariloche, I grew up there, always in contact with plants. When I was a child, I used to crush them, I made perfumes, I tried to generate things with them; when I grew up, I decided to study art and went back to that practice. Today I only work with dying and medicinal plants.

My research relates to is my perception of the universe and the world. It has to do with rescuing ancestral practices, trying to trace those mythologies that are often not so easy to find.

How is your research process composed?

My research process has to do a lot with experimentation, I am always looking for plants that are dyeable.

For that, I first look at ancestral textiles, where there is a lot of information about dye sources. I also work with healers, doctors, homeopaths, where I find another source of research. In addition, from original mythologies I can also find out which plants may have dyeing capabilities.

Finally, there is a lot of experimentation: every time I come across a plant I try to see if it has dyeing capacities or not. I macerate the plant, then boil it and test it with light by placing the dyed wool or paper in the sun for a month. If in that month the color does not vary that much or does not disappear, the plant is dyeable. So, my work is almost an experimental kitchen.

What is the process by which you create your textiles?

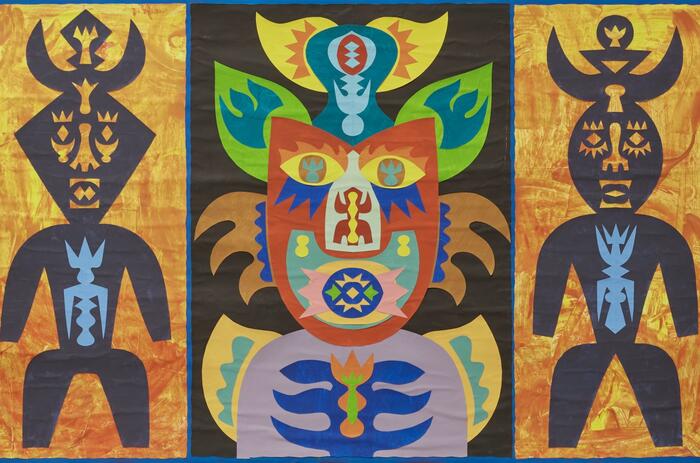

I think of color as an expansive wave of health and knowledge which its original source is a plant with medicinal, mythological, and dyeing capacities.

I think of the media regarding each material's different capacities: an engraving paper is not the same as an absorbent paper or a watercolor paper. On the other hand, vegetable dyes go very well with animal fibers. The color of a plant will shine more brightly if I put it on animal fiber. It can be silk, or wool, there are some exceptions that are on cotton.

The medium has a fundamental role, because it is where I can materialize all this ancestral knowledge.

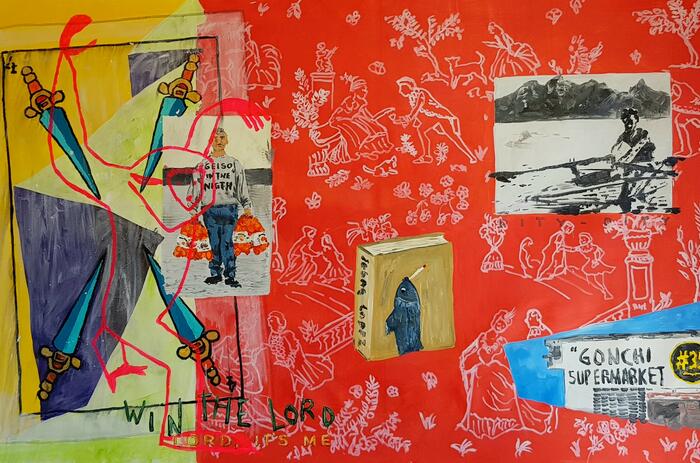

If I use felts, I make them myself, kneading them in the studio. I think of the felt as a piece of paper, I dip it in the color. And then I dye the wool and embroider it. It is a very pictorial search that I continue. The same with the works on paper, that after I have developed this knowledge of dyeing, I focus on thinking about the color on the support.

How do you decide on the color?

It is more intuitive. I assemble the dying material, freeze it and form cubes of color that I then place on blotting paper to melt. They remain as glaciations and it is with that same plant of origin that I dye the wool and then I start embroidering, following the initial stain left by the first color cubes.

This material absorbs the water and leaves the stain. First the paper is dyed, which is the kick to continue searching for the image intuitively. It is to deploy the knowledge of color as much as possible.

Finally, I dedicate myself to pursue that initial image.

What are you presenting in this edition of Pinta PArC?

For this edition of Pinta PArC I'm going to work on a mural painted with palo mora and there will also be some textiles made with felt and fabrics, looking for a very pictorial form using wool dyed with medicinal plants. There will also be works on paper, intervened with different colors of plants and wool. All this will be in dialogue. Although my research is about medicinal and dyeing plants, in the end the result has to do with a very pictorial pursuit.

How does the notion of territory influence your production?

For me, the notion of territory has to do with thinking of a color map based on the different places where I am. If I move closer to the equator, the colors will be much brighter because the plants are softer and bring out much brighter colors. As I go south, the colors are darker, and there is not as broad a palette. It has to do, first with what you see, which is eventually reflected later in the dye, and then with the hardness of the different leaves or seeds.

My ideal in the future would be to be able to make a medicinal tinctorial map of the world.

What influence does traveling have on your work?

It is very important for me to be able to travel in terms of my work because for me it allows me to find new tinctorial and medicinal sources. There is always something that opens up because there is new knowledge, new flora to investigate.

What is the place of tradition in your work?

Tradition runs through my work because I try to recover certain ancestral knowledge, but I am not interested in tradition as something crystallized, but as something that is transferred orally, such as mythological and Latin American knowledge.

How do you think temporality affects the perception of your work?

On the one hand, I am always aware of the seasons, because according to them, my palette changes a lot. Summer is not the same as autumn, because the colors I can get in each season change a lot, although I can also save and store them.

On the other hand, the works that are on paper, wool or felt I crystalize them because there is a natural method that allows the color to remain. But when it comes to installations on walls, I try not to fix them so that they have this variation over time. I can allow myself to do this because the installations then fade. Like the trees that change, this is playing with the same thing.

I can play with the ephemeral, that is erased, that changes. If I don't fix a color, I know that it will radiate somewhere else, or it will disappear.

What role do you think art plays in the preservation of collective memory and ancestral practices?

I've always been very curious about mythologies, it's something of my own cosmovision, and there, trying to find those stories is also where the impulse to look for something more in plants appears.