ONCE WARHOL’S MUSE, NOW FORGOTTEN IN TIME: MARISOL ESCOBAR

In April 2022, my family suggested we attend the opening of an exhibition by Marisol Escobar, a French-Venezuelan artist whose name was vaguely familiar to me. I wasn’t particularly excited, but wanting to spend time with them, I agreed to go. Little did I know that this visit would leave an incredible mark on me.

As we entered the museum, I was immediately drawn to Marisol’s wooden ensembles. They were unlike anything I had ever seen—raw, expressive block-shaped sculptures with intricately painted patterns and eerily lifelike faces. Standing before them, I felt an unexpected wave of emotion rise within me, bringing tears to my eyes and goosebumps across my skin. These weren’t just sculptures; they were profound stories carved into wood, each figure conveying a depth of feeling that words could never capture. Her work spoke to me in a way no other artist had, and as I delved deeper, I began to understand why.

Marisol Escobar, often simply known as “Marisol,” was a prominent figure in the New York pop art scene of the 1960s and 70s. Born on May 22, 1930, in Paris to Venezuelan parents, Marisol’s early life was one of privilege, marked by frequent travel and exposure to diverse cultures. However, her childhood was also shadowed by profound personal loss. Her mother, Josefina Escobar, committed suicide when Marisol was just eleven years old. This tragedy deeply affected her, and in response to this overwhelming grief, Marisol made a personal and solemn pact of silence—a vow that would shape her life and work for years to come.

Her silence wasn’t merely a withdrawal from the world but a conscious decision to reserve her voice for moments of true necessity. Marisol’s most potent and eloquent expression found its outlet through her art. Her unconventional carpentry and often enigmatic sculptures transcended the mere physicality of wood, captivating the eyes of thousands within the booming New York art scene. Marisol’s ability to convey depth and mystery without words resonated deeply with those who encountered her work. This silent power attracted the admiration of visionary figures of her time, including Leo Castelli, Andy Warhol, Willem de Kooning, Sidney Janis, and Franz Kline. Yet despite her unprecedented success, one can’t help but wonder—what happened to Marisol Escobar?

During the late 1950s and 1960s, Marisol reached the pinnacle of her career. In 1957, she was featured in a group show at the legendary Leo Castelli gallery alongside Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg. The show was a resounding success, catapulting her to fame, but Marisol was uncomfortable with the attention and reputation that followed. In an attempt to escape the limelight, she fled to Rome for three years, cutting off almost all contact with the New York art scene—a move that would become a recurring theme throughout her career.

When she finally returned to New York in 1961, Marisol was welcomed back to the art world with open arms. She was featured in The Art of Assemblage, an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), alongside works by Pablo Picasso, Marcel Duchamp, Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Louise Nevelson, and Jean Dubuffet. Her 1962 solo exhibition at Eleanor Ward's Stable Gallery became a landmark event in the New York Art Scene. By 1964, her second show at the gallery drew up to two thousand visitors a day, featuring her iconic work titled “Andy” . During this time, Marisol and Andy Warhol became close friends and collaborators, introduced by their mutual friend Mimi Trujillo. Warhol was drawn not only to her striking beauty but also to her unique, confident poise. Her ability to convey depth and mystery with minimal expression resonated deeply with Warhol, making her an ideal subject for his cinematic and artistic vision. He featured her in two of his experimental films, The Kiss (1963) and 13 Most Beautiful Women (1964). According to Mimi Trujillo, a longtime friend of both Warhol and Escobar, “She was the queen of the city. No one could stop her. Andy and Marisol were close friends during this time. However, she was undoubtedly a much larger star than the then aspiring illustrator, Andy Warhol.”

-

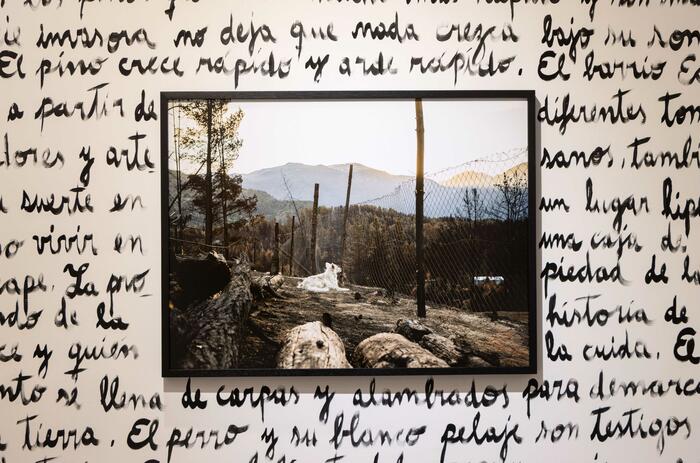

"The Party", un grupo de más de una docena de invitados elegantemente vestidos que comparten el rostro de Marisol. Cortesía del Museo de Arte Pérez de Miami

In 1966, Marisol began a professional relationship with her longtime dealer, Sidney Janis, through her first solo show at his gallery. Thousands lined up daily to see her work, which was featured in leading magazines such as Time, Life Magazine, and Harper’s Bazaar. Her success continued to grow, culminating in a landmark solo exhibition at the Sidney Janis Gallery in 1966, solidifying her reputation as a leading sculptor.

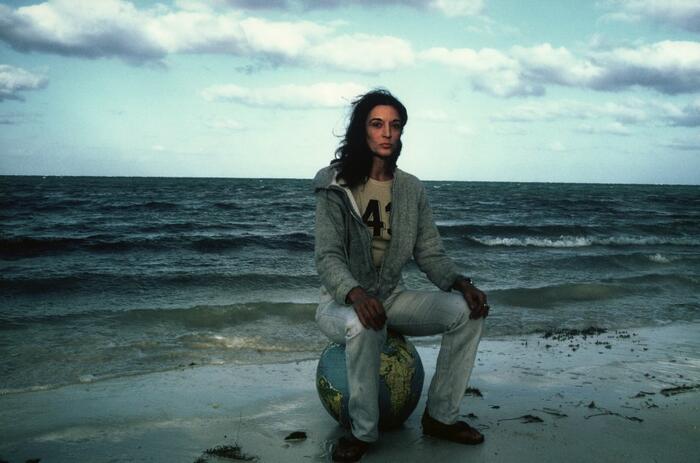

Two years later, in 1968, Marisol represented Venezuela at the Venice Biennale. Following this achievement, she once again felt pressured by her success. She left for a two-month break to Tahiti, where she learned to scuba dive. She became enamored with the ocean, finding peace, quiet, and escape from the pressures of human life. The two-month break extended into four years as Marisol traveled the world, leaving behind New York and the art scene once again.

However, when she returned to New York, the art world was not as forgiving as it had been before. “After her return to the city, it was clear there was a new king in town, and his name was Andy Warhol,” as told by Mimi Trujillo. Despite this decline in public interest, Marisol continued to create, but she was never able to recapture the heights of her earlier success.

In 1973, she produced a show at the Sidney Janis Gallery, dedicated to the aquatic creatures she had seen during her scuba diving adventures. Despite the unique and innovative nature of her work that year, critics were not fond of it. For example, Peter Schjeldahl of The New York Times described the works as narcissistic because the fish works, she created all had her face—a recurring theme in much of her work. This show marked a decline in her commercial success.

For further insight, I spoke to Carlos Mota, who had a close working relationship and is now a world-renowned interior designer and author featured in Architectural Digest’s AD100. Carlos began working with Marisol in 1986. By this point in her career, she reportedly worked only at night, and Carlos had to adapt to her schedule. Marisol rarely left her Tribeca apartment and preferred to work in isolation. “She wouldn’t leave the house. She frequently asked me to get her groceries and food, and even made me pay for them. We would work long nights, hand-painting. It was a remarkable experience but difficult to maintain. New York is a city that moves fast; if you’re not showing up every day, the city will forget you like you never existed.”

Another contributing factor to her commercial downfall was her lack of interest in monetary gain. “Marisol didn’t care much about money,” said Mimi. “I remember a time when she was struggling financially. A printmaker offered her a deal where she would make $100,000 upfront, but she refused. I told her, ‘Marisol, you need this!’ But she didn’t listen. She preferred to work with the company she had always been loyal to, despite needing the money.” This, along with her frequent hiatuses, suggests she was creating for the love of her craft and self-expression rather than for financial success.

Marisol was a misunderstood genius—a complex person with layers that not everyone could see. Those who knew her described her as both intricate and deeply thoughtful. It’s clear that Marisol wasn’t motivated by fame or fortune; she was a true artist, creating from a place of personal passion and self-expression.

Reflecting on my experience at the Museum, I realize it wasn’t just the visual appeal of Marisol Escobar’s work that struck me, but the raw emotion in every piece. And now I know why Marisol Escobar's work spoke to me in a way no artist ever has.

-

Marisol y Mimi Trujillo cortesia El Miope.

Editor’s note

Marisol's oeuvre is experiencing renewed interest with the exhibition 'Marisol: A Retrospective' currently being presented at four venues across North America: the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (October 7, 2023 – January 21, 2024, now closed), the Toledo Museum of Art (March 2 – June 2, 2024, now closed), the Buffalo AKG Art Museum (July 12, 2024 – January 6, 2025), where it is currently displayed, and it will travel to the Dallas Museum of Art from February 23 to July 6, 2025.

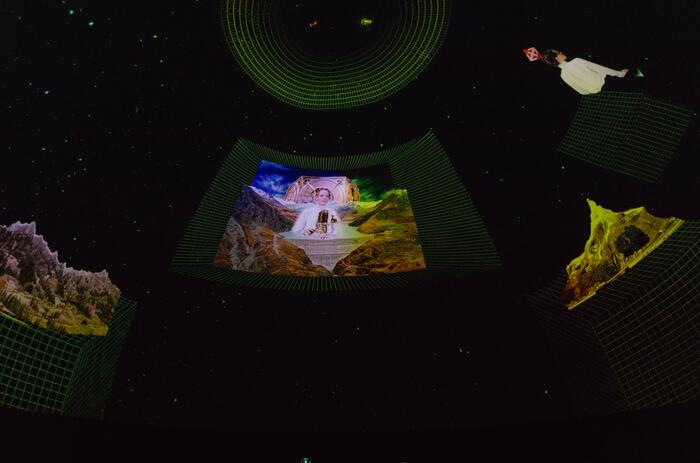

"Marisol: A Retrospective" is a comprehensive touring exhibit of Marisol Escobar’s work, featuring nearly 250 artworks spanning her six-decade career, including sculptures, drawings, and other media, along with previously unseen archival materials and ephemera.