INTERVIEW WITH TANIA PARDO, NEW DIRECTOR OF CA2M MUSEUM

Tania Pardo (Madrid, Spain, 1976) is the new Director of the Museo Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo (CA2M Museum), the museum of contemporary art of the Community of Madrid. Pardo's career until her recent appointment has been built on a detailed work of promotion and visibility of emerging art through the curatorial actions she has developed in numerous Spanish institutions.

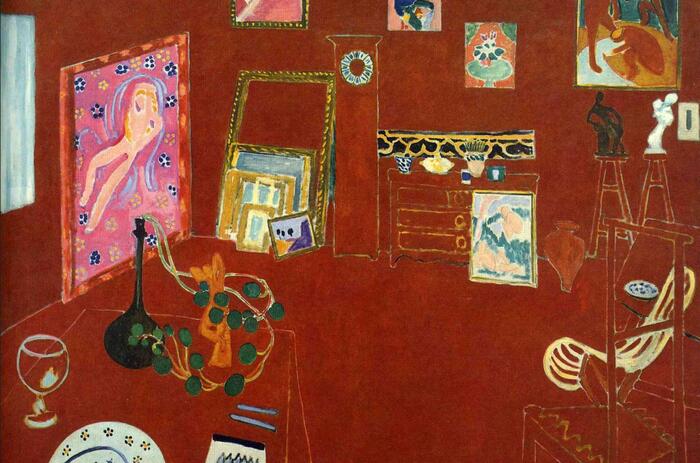

Navigating between the needs of the public and the private, her dynamic bets have had as scenarios museums like the MUSAC in León and its Laboratorio 987 or La Casa Encendida in Madrid, where she was in charge of the Exhibitions Department until June 2019. That same spring, she became deputy director of the CA2M, where she began a fruitful professional relationship with Manuel Segade to continue shaping the attractive idiosyncrasy of the Madrid institution. After Segade's appointment as Director of the Reina Sofia, and following a public competition, Tania Pardo takes over the direction of the center located in Mostoles with new and old challenges ahead. She receives this interview in the museum's offices, whose walls are plagued with posters of exhibitions that have been fundamental in the creation of institutional identity. Before starting the dialogue, we stand in front of one of them, from Sonic Youth's exhibition etc.: Sensational Fix (2010), which serves as a framework to comment on the importance of that milestone for what it meant in substance and form.

Álvaro de Benito (Á.B.): Having already worked as deputy Director of the CA2M Museum, from the curatorial part to the institutional part, do you have a different vision than the one you've been developing when you became director?

Tania Pardo (T.P..): Assuming the position of Director through this public competition also means taking on a responsibility, since it is the first time that I am at the head of an institution, although, obviously, with the advantage that I was already part of the team for almost five years together with the previous director, Manuel Segade. I think what changes is that the vision must be more global and institutional, also focused on management, on taking care of a team, etc. Facing all this is the challenge because I've had a professional career where I've always felt very sheltered next to enormous professionals: from MUSAC with Rafael Doctor and Agustín Pérez Rubio or, in La Casa Encendida, linked to José Guirao, Lucía Casani, and, recently, with the deputy director of the CA2M Museum creating this tandem with Manuel Segade, which has been one of the best professional experiences so far. They have been incredible years of learning and that has given me a lot of strength and enthusiasm to take on the direction. There is also a clear advantage, as I said, and that is that I know the center very well, the team and, affectively, I have a very strong bond since the museum opened in 2008 because with Ferran Barenblit, the first director, I was invited to make an exhibition (No heroism, please, 2012) and from that moment, for me, the CA2M Museum will become a benchmark for approaching contemporary art.

Á.B.: There is a recurring issue with relays and that is the transition period that is covered by captive programming, inherited from the previous management. I don't know if this is necessarily a negative thing in your case, if it ever is. I am referring, logically, to the actual change in policies you want to execute.

T.P.: This question is often asked, isn't it? How and what the differences will be? I believe in organic processes. I come from being next to an extraordinary person, Manuel Segade, programming together, so I'm going to try to preserve that heritage and all that energy that is already the heritage of the center itself. The CA2M Museum is very well positioned internationally and nationally is a legitimizer of art scenes, but, in turn, there is much lack of awareness at street level and more in that citizenship that is not so linked to contemporary art. And perhaps that is a great challenge that I would like to assume, that everyone knows that they have a museum that is waiting for them. I would also like to open the door to disciplines that have not been so well attended, such as illustration, design, continue working on architecture projects, and generate a very strong line on physical, cognitive and mental health accessibility through the Cosmorama Program, also related to social insertion. On the other hand, I am interested in constantly questioning, through different activities, what public museums are for in the 21st century and to make the institution's backroom visible, for the moment through a networking project that will show all the departments. My wish is that the CA2M Museum reinforces the idea of continuing to be a choral, polyphonic, diverse institution, an institution that “talks through its elbows”. These seem like very basic gestures, but they seem very necessary to me. To make institutions more friendly because, in the end, they are formed by people.

A.B.: You talk about the issue of recognition of CA2M Museum. Would you say that there is a CA2M brand as such, recognizable? And if there were, how would you define it?

T.P.: We have talked a lot about it being a “low institutional” museum. This is a concept that Manuel Segade puts on the table and I'm going to pick it up. This means that it is a center where you don't have to pass your bag through any detector and where nobody asks you where you come from. The museum is conceived as an extension of a house, a place to be, inclusive. This does not mean that in an exhibition there is no confrontation, because we also work with conflict, with affliction, that makes us think, but that makes you stay and want to come back. And then, continue working on the context itself in which it is geographically located. We are a center located in a city like Móstoles, in the south of the region, which makes us very different from the north. As Joaquín Torres García and his “Our north is the south”, a phrase I use a lot as a metaphor for this CA2M Museum, as well as the concept of the multiform, a museum capable of mutating and adapting its forms to different situations, contexts, artists and audiences.

A.B.: However, the CA2M Museum represents, on paper, the institutionalism of a region like the Community of Madrid and, sometimes, I find it complicated how that circumscription can affect a universalizing eagerness. You were commenting before about the knowledge of the museum internationally, but the conjunction between this nominal regionalism and the universalization of the content can be perceived sometimes quite strange.

T.P: It is very important to know the place we occupy and to know where we stand. The CA2M Museum handles universal languages, this is intrinsic to art itself. It is a museum that cares a lot about its geographical position, but the language is transversal. This is demonstrated by the exhibitions of artists who can be at the CA2M Museum, the Reina Sofia, the MUAC in Mexico, the Venice Biennial or the PS1 in New York. Thinking in that context, for example, you can't understand Madrid without Latin America and you can't understand Madrid without a north and a south, you can't understand Madrid without Móstoles and, above all, you can't understand the CA2M Museum without Móstoles, because if it wasn't here, it wouldn't be this museum, it would be something else. We work with that idea of decentralization, of eccentricity, because that eccentricity —not being in the center— has allowed us to work looking at many places without forgetting that Madrid historically is and has been a place of legitimization for the art scene. Besides, a place like Móstoles produces its own affective richness, since is where some of the largest populations of Guineans, Arabs and Latin Americans in Madrid coexist, and this allows us to work willing to exchange and learn constantly, and I think that's where public institutions should tend to.

A.B.: That concept of the periphery is something that has obviously been present very often in that institutional narrative of the CA2M Museum. I find it interesting to understand if the whole periphery concept, as, for example, the Latin American within the social structure, integrated with the periphery, has become more of a centrifugal concept than a centripetal one.

T.P.: I want to understand the peripheries as places of the center and the centers as peripheries, to turn the maps upside down, to invent them. That is why I said that our north is the south. Another important concept of the museum is the application of radical imagination. The periphery has made it possible to work displaced from the focus of centrality, but these are questionable concepts: can one be the center from the periphery? Museums are places to think, but also to experiment and allow encounters with the works. Artists are themselves a pedagogical artifact, places open to the exchange of learning.

A.B.: You alluded to a physical characteristic of the CA2M Museum, that of a museum where no one has to pass through a security filter. Taking advantage of the metaphor, is there such a security filter with respect to the curatorial or exhibition aspects of a public institution? That is to say, to what extent does the idiosyncrasy of a public institution affect the programming?

T.P.: It affects in the sense that when it comes to programming, there are clear lines of exhibitions and activities. In this institution, which was born with a public collection that increases every year, at one point the word museum was lost, a word which we recovered two years ago. The difference between an art center and a museum is that art centers do not have a collection and museums do. Perhaps this word was lost along the way for an almost cacophonous reason —MCA2M—, but we recovered it and this has meant working between the dynamism of an art center and the rigorousness of knowing that it is a museum that has a public collection that belongs to all of us. Because forming a collection is another great responsibility, since they are heritage and are always choral and polyphonic. For its formation many looks enter, it is always incomplete, stories are missing. I am very interested in the margins, the intrahistories that do not enter into the official narratives and that I would also like to promote at curatorial levels. Going back to your question, I'll tell you that the CA2M Museum has always been given great support, even assuming error and misunderstanding as part of its own story.

A.B.: This issue is linked to the political criteria followed by the administrations and that can be reflected in the museum's activity. And not only in terms of that management, but also in terms of exhibition policies and curatorial dynamics hijacked by trends that have been built from urgency and perhaps with ulterior interests.

T.P.: Of course the art world is no stranger to our own neoliberal and capitalist world in which we live and, undoubtedly, there are curatorial fashions that, in turn, are closely related to market trends and their great impact on our system. There have always been fashions. For example, photography in the early nineties or video, but also thematic ones. The important thing is to discern what you do and defend to get out of what is in fashion, to have the tools to generate your own languages, even assuming that you are willing to make mistakes and, at other times, to contaminate yourself with those fashions. But these are the controversies of the art world and its complexity.

A.B.: In those mercantile dynamics within an art industry, in addition to the support or the technique you mentioned, there are themes that end up being mercantilized as well. For example, it is being observed that, within the great lines of argument in the Western societies, identity, sustainability and decolonization have a very relevant position of strength. There we are also seeing those policies and those public positions that, by action or fear, indicate what is to be bought or what is to be exhibited and to be didactic with it.

T.P.: These are very controversial issues in the art world itself, because art is one thing and its system is another. There is something cynical and amusing about all this, because you confront different discourses, the projection of the artists or how we tell them. Many times, I question myself if it is possible to stay away from fashions. I aspire to be a bit timeless, but sometimes thanks to these fashions very interesting and pertinent debates have been put on the table, such as those concerning gender, feminism, issues related to racialized minorities, LGTBI+ discourses, etc. Sometimes it is difficult, but I want to believe that it is achieved. Maybe it is utopian, but so is art itself and it has to be.

A.B.: Do you think there is independence in the art industry? I don't know if it can be perceived that this base, which is artistic production, has lost its creativity for the sake of being a catalyst of a public service or of having to follow a discourse that is popular.

T.P.: That is a very good question. I don't think it is lost. In fact, I think the mission of the museum is not to get lost there, but to be able to listen and interpret very different positions so that it really is a diverse and polyphonic place, to gather plural narratives and to have different programming and even to appeal to contradiction. I want an institution to have room for many voices because if only one voice is heard, there is a problem. Getting there is not easy, but that is the great challenge: let's try!

A.B.: However, I think there can be some pressure if you go outside the discourses in vogue. If you look at the topics and the lines of argument of the biennials, of the museums, they are practically hegemonic. Maybe the gallery has a minimum of power to get out of that discourse.

T.P.: But we also have to ask ourselves a question with a complex answer: who makes the institution, is it those who are in charge of it that make the institution or is it the institution that makes the curators? I think one has to work without pressure, trying to get out of the imposed discourses.

A.B. Would you answer that question?

T.P.: I question myself many times, because, in certain cases, there are personalities that mark the institution a lot and set a trend. I feel very comfortable in this museum because it has very moldable characteristics and a great team of professionals to work freely, without forcing any speech, without imposing any gesture. For example, right now the institution has three exhibitions by three women artists —Asunción Molinos Gordo, Teresa Solar Aboudd and Ana Gallardo— together with the capsule collections, which are coincidentally also by women —Ángela de la Cruz, Ixone Sádaba, Emily Jacir and Eva Fàbregas—, but everything has been programmed in a very organic way.

A.B.: I am very sceptical about these organic inertias because, just as in the neoliberalism and capitalism we were talking about and which marked these tendencies, there was an invisible hand behind them, this same hand generates tendencies. So, in the end, we are not so independent in our decisions, and even less so when you are doing that service or that public work.

T.P.: Of course, I am also aware that the gestures made by the institution are also legitimizing. I have experience in many different environments and I have worked in different institutions, but I have also been independent. It is important to know and be contaminated by everything that happens around us and to know, going back to one of the previous questions, from where one speaks. I am very interested in the institutional language and from there to be attentive to other languages, to know different spaces and artists. For example, Madrid is made up of many scenes, which must also have a place in the museum. Without forgetting that, in the end, you become a legitimizer, because that's what a museum is, a legitimizing entity.

A.B. Especially because once you legitimize, you have the task of prescribing, of trying to consolidate what you have legitimized and, for that, there must be very strong discourses, but taking into account the interdependence you also have with the visitor, with the spectator.

T.P.: That's why you have to be, I think, freer and more independent. What's more, it is the artists' right to make mistakes and our duty is to accompany them. The museum has to be that welcoming space for artists, a place open and constantly listening, always alert, attentive.

A.B.: You've commented on several occasions that, for you, art galleries should be an unavoidable part of the museum management system. What role do you think they should play within this whole ecosystem?

T.P.: The gallery is a place where art is fundamentally traded, but gallery owners are also very important figures for the historical accounts of the art system itself. There are historically fundamental gallery owners and galleries. They also have that role that makes it possible to show art that could not have been seen in any other way. For institutions, galleries are very important when it comes to acquiring works of art, although artists who do not have galleries can also be acquired, obviously, but I am referring more to the fact that galleries do their job by proposing, making visible and supporting the work of artists. Sometimes they can make gestures that perhaps the public institution cannot afford, and that is why they are a very important part of this system. I believe that in these times we live in, galleries are immersed in a process of reinvention, because they are changing, complex and complicated spaces. The art system is full of great professionals, including professions that are not sufficiently visible: exhibition coordinators, designers, art critics, post office staff, restorers, etc. I will always vindicate the role of galleries, and also personally, because they have served me very well in my training as an art historian.

A.B.: In the more commercial sense, in Spain and in most of Europe there has been a very clear bet by galleries on Latin American art. Many years ago, I was talking to Jesus Carrillo, who was in charge of Conceptualismos del Sur, and I asked him a question that can be controversial as to what extent Madrid or Spain can act as that explosive metropolis of what happens in Latin America, a metaphora that can sound antagonistic to the decolonizing discourse. I'd like you to tell me about the position and importance Latin American art is going to have in the CA2M Museum within that more local society you mentioned that has been created and that has consolidated that multiculturalism and if you think Latin American art has to be a reflection of it or has to be independent.

T.P.: In the end, art is a reflection of the society we live in. In the Middle Ages they explained the works through art and the capacity of the studio is similar. Before I was saying how this city, in Spain, cannot be conceived without Latin America. I cannot understand it in any other way. We have been working for many years with Latin American curators and in the last few years there has been a great increase of Latin American art in the museum's Collection. We have also co-produced exhibitions with Latin American museums and the relationship is very fluid. I am thinking now of exhibitions that have been held at the CA2M Museum by Jorge Macchi, Carlos Garaicoa, Cecilia Vicuña, Patrick Hamilton, Ana Gallardo, Wilfredo Prieto, etc. This year, Sandra Gamarra, a Spanish-Peruvian artist who has been producing here for decades, is even representing Spain in the pavilion of the Venice Biennale, curated by Agustin Perez Rubio. You can't understand a museum here without Latin America, without the decolonial discourses, it can't be otherwise. If you mean that these themes are present in the more mainstream discourses, why can't they be? Contemporary art, art in general, has to ask questions, but it doesn't have to give answers. In addition to constantly questioning, we must also allow ourselves to change our minds and even advocate hesitation.

A.B. I'd like to ask you a somewhat basic and generic question: What lines of action do you intend to follow in the curatorial work of this new stage of the CA2M Museum?

T.P.: We will continue to be a production space for young artists and those with medium and consolidated careers, both local, national and international. It will be essential to propose new perspectives on the CA2M Museum's collection and on the ARCO Foundation's collection, which is also kept in the museum and with which we work as a single body. Study and work groups will be generated orbiting around the museum, focusing on various themes that cut across the collection. In fact, the first research group has already been created and will be announced in June on art and reclusion. This is very much related to understanding art as a tool with a transformative capacity and a whole social side that is of special interest to me. In fact, for the last year and a half, I have been doing research by visiting and teaching contemporary art classes in different men's prisons in the Community of Madrid. I am always questioning almost everything I do. Within the exhibition lines, there will also be one more focused on the vernacular, which is also related to the popular and is a legacy of the museum since its opening. Earlier we talked about the importance of music, Pop Politics. Activisms to 33 Revolutions (2012), of PUNK. Its Traces in Contemporary Art (2015) or Elements of Vogue (2020), because for us it is a fundamental line. Another of these lines will be the attention to the Portuguese artists' scene.

A.B.: Of course, a priori you've got a lot of tools and experiences, and some of them are already consolidated in that institutional imaginary, that of the everyday, the integration, the periphery, to be able to execute that continuity and innovations.

T.P.: I have made numerous exhibitions that spoke precisely of attending to the most everyday look, to the minor gestures. And this, of course, in terms of direction, I want to promote it. I am very interested in focusing on what is closest, on what apparently goes unnoticed, but also on the margins. For example, we will continue to work on the visibility of women artists who have not been present in the canonical history of art, but also on those minorities nearby. The next Jornadas de la Imagen will be directed by Pastora Filigrana, one of the most recognized voices for human rights activism of gypsy origin.

A.B.: In that sense, it is striking that the industries in Spain and part of Europe allow themselves to be carried away a lot by that Anglo-Saxon colonialism, in which the structural problems of the United States or UK, which are radically different from those of Spain, have to be ours as well. In a reality made up of 700,000 gypsies in Spain and millions of Latin Americans, it seems that they never exist in the approaches of the multinationals, which, for example, in publicity and integration policies, shuffle everything in front of purely Anglo-Saxon factors.

T.P.: That is the reason why I talk a lot about the context in which we are, about proximity and the importance of looking more closely at what is close to us. It is enough to look at something closely for it to become interesting. This is something that happens to me, but in a universal sense. I like to speak from the smallest and closest to talk about universal themes. Related to some lines you mentioned before, I give you the example of the eighties in Spain, of the mothers of Orcasitas [a barrio in Usera district, in Madrid], who were the first to form an association of mothers of children lost to heroin. And while the mothers of Orcasitas are here, what happens at that time in Ireland with the miners? That is, to be able to draw lines from here and there disparate and similar in time.

A.B.: Earlier you underlined that the CA2M Museum is a museum that has a very consolidated reputation in the international scene, which could be equivalent to the elitist, to that class of people who know it, but there is still a long way to go in that part of popular knowledge. I think it is obvious in that CA2M brand a very clear tendency towards youth, with programs focused on young people in their participation and as recipients of, for example, music festivals, and also that intention you mention now with the exhibitions that can be meant as a break towards the traditional in the exhibition and the institutional in contemporary art. How much of all that approach is instrumental, precisely, to break barriers?

T.P.: The younger public is fundamental in museums. They must take ownership of them, break the way to approach them. From the Education Department, the Museum works a lot with and for them through the Sub21 Group. But socially, when we talk about young people not visiting museums, it is a question related to the educational system of our country, which does not encourage the study of Fine Arts. Since we are young, how many people are used to visiting contemporary art galleries? They are free spaces and a source of learning to see art, but sometimes unknown to a public not accustomed to contemporary art. We have to break down prejudices on the one hand and on the other. Who puts the other side? At the CA2M Museum we work to generate these learning tools. I think that, in education itself, in our system, it is more important for one to learn what a 5 is, than to let the child imagine that a 5 is a winding snake. Creation, multiple intelligences, understanding have not been worked on enough and we are in very polarized societies. We are trained to be production machines, hence the importance of museums. It is important not to be afraid to question art, even if you don't like something, to be able to express it. Young people are transmitters for the future, but we also have to break that ageism and rethink this society that constantly mythologizes the young. From the CA2M Museum department, we work a lot with young people. Here, in Móstoles, there is no mall, there is no cinema, and the museum becomes a public service that offers cinema and the possibility for them to take on the museum as their own. Around the CA2M Museum orbit collectives that have made this place their own, such as Las Tejedoras, who have been weaving together for ten years at a table next to the cafeteria. They belong to Tejiendo Móstoles and are the metaphor of that affective network we talk about when we refer to the museum's actions. In May, they will occupy the museum, they will weave wherever they want. If any of them wants to knit in my office, they will knit here, just like in an exhibition, and we will end this day celebrating them with a party in which they have chosen the music to dance to. We want many things to keep happening in the museum at the same time. And to be able to claim the present as the time in which to stop: an unstable, polarized, difficult present, but in which very interesting things are also happening, and that is where we want to go.

Á.B. What do you think is the most challenging part of your assignment, the most complicated for the CA2M Museum, its environment and what it represents?

T.P.: When you talk about institutional languages, you have to allude, on the one hand, to the rigor and, on the other, to the responsibility that this entails. But perhaps the most challenging thing is to continue generating a place that gathers the diversity of art and all its possible languages. That the museum be a space that welcomes the multiple scenes in order to continue collaborating with its agents and to preserve and attend to the agents that form it. Art and its system are very fragile places, and the institutions have the duty to try to solidify it.