JULIA ISÍDREZ AND THE GLOBAL SOUTH AT THE 60TH VENICE BIENNIAL

A week away from its official opening, the 60th edition of the Venice Biennale has generated press urbi et orbi. While some articles celebrated the irruption of the Global South in the Arsenale and the Giardini, others -truly devastating- reported on the disturbance and discomfort that the proposal of Adriano Pedrosa -the first Latin American to cure La Biennale in more than a century of existence- has awakened in the Western art system.

Getting to Venice is not easy, both literally and figuratively. The world's biggest art event -to which only Documenta disputes prominence- has been conceived this time as a “celebration of difference” that, by the way, can't escape the risk of exoticization that hovers over this edition in which 331 artists from all corners of the planet have been gathered under the title Stranieri Ovunque (Foreigners Everywhere), with 87 national pavilions and a number of parallel exhibitions and events.

It is a complex and comprehensive curatorial construction that can be seen as a “collection of marginalities”, an infinite sum of stories of exclusion and diaspora, of resistance and obstinacy, sometimes presented in a friendly format and sometimes in a conventional one. A transcultural, transdisciplinary, transsexual and open exhibition that plays with anachronism not only in its two historical cores and whose ambition to vindicate the immigrant, the foreigner, the queer and the indigenous ends up homologating diverse situations, practices and contexts.

The expression Foreigners everywhere has several meanings. “First, wherever you go and wherever you are, you will always find foreigners - they/we are everywhere. Secondly, no matter where you are, you are always truly, and at heart, a foreigner,” says the curator in his statement.

-

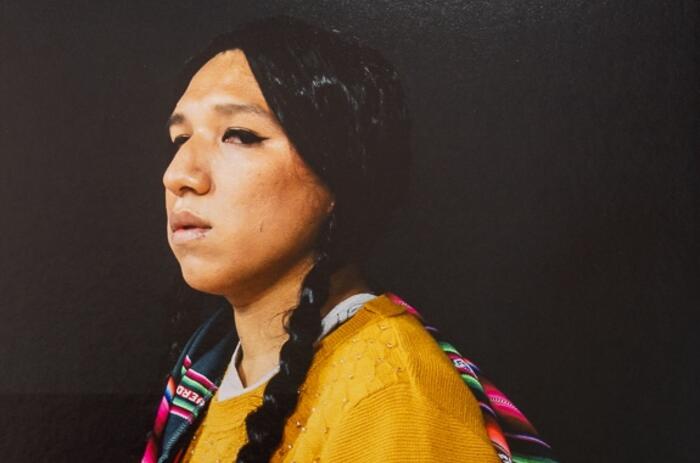

Julia Isídrez. 60th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere. Photo by: Marco Zorzanello.

-

Julia Isídrez. 60th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere. Photo by: Marco Zorzanello.

-

Julia Isídrez. 60th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere. Photo by: Marco Zorzanello.

In this welter of diversity, the works of two Paraguayan folk ceramists are shown in a privileged place, the Arsenale di Venezia, as part of the main exhibition curated by Pedrosa. Almost at the beginning of the tour, in the center of one of the great enclosures, the pieces by Julia Isídrez and her mother, Juana Marta Rodas, share space with works from different latitudes. This is the first time that artists from Paraguay are part of the main exhibition by direct invitation of the curator.

Julia's participation was entirely articulated from private sources. The São Paulo gallery Gomide&Co -which represents the artist- took charge of the logistics for the transfer of the works and the Biennale assumed the costs of her presence in Venice. Paraguayan gallery owner Veronica Torres, who traveled with Julia, played an important role in the process from the beginning. Also relevant was the affective and professional support of Jorge Enciso, Julia's disciple, artist and lawyer.

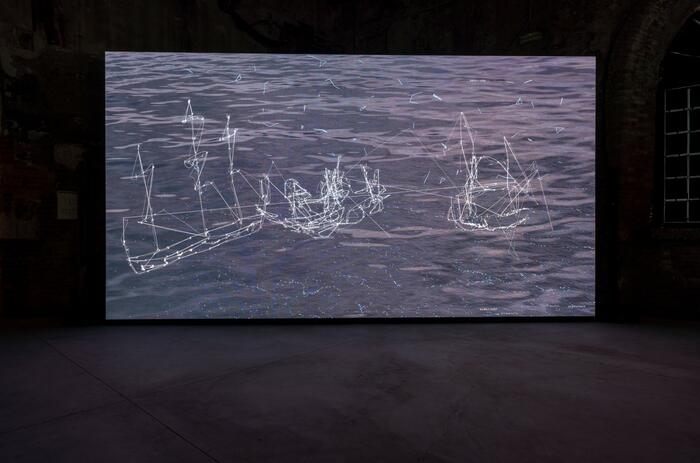

Unlike Julia's large volumes (some are around 150 cm high), Juana Marta Rodas's pieces are small and belong to the collection of the CAV/Museo del Barro, in Asuncion, the institution that loaned them, in response to Pedrosa's request. Both, mother and daughter, have aroused interest in the international art circuit for some time now. It should be recalled that in 2012 works by both were present at Documenta 13, in the Rotunda of the Fridericianum Museum in Kassel, in friendly proximity to Brancusi's sculptures. And that several years earlier they had been awarded the Prince Claus Prize in Holland. It should also be noted that Aracy Amaral curated Isídrez exhibitions in Santiago de Chile and São Paulo, in collaboration with Osvaldo Salerno.

-

Julia Isídrez. 60th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere. Photo by: Marco Zorzanello.

-

Julia Isídrez. 60th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere. Photo by: Marco Zorzanello.

-

Julia Isídrez. 60th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere. Photo by: Marco Zorzanello.

Although Julia's intense schedule in Venice, with interviews and meetings, contrasts with her days in Itá, where she has her home and a museum dedicated to her mother, her activity is always frenetic. It has always been, and today more than ever, with two international exhibitions coming up - one in New York and one in London - an upcoming biennial and the school she is building on a recently acquired piece of land, where she will teach classes and organize artistic residencies.

The image of Julia as a child, in the countryside, accompanying her mother very early in the winter to the place where Juana Marta extracted the clay for her works is well known. A long time has passed since then. So much, that the world, like her, has changed, although it is still the same. So much so that her pieces took on mythological, whimsical, fictional forms as they moved away from any utilitarian function. Julia's imaginary, like her mother's, was inexorably oriented to the territory of art and this patient and sometimes tiring navigation reaches today a coveted port with important stops along the way.

Hundreds of artists like Julia, unknown in the global art circuit and even in their own local scenes, who have never exhibited in this Biennial and perhaps not even in others, are a majority here. In fact, the long list of participants includes both individuals and collectives, many of whom never assumed themselves to be artists. Fresh works and ad hoc realizations coexist with pieces by disappeared artists or anonymous artifacts. The living mingle with the dead, at a ratio of 100 contemporaries to 200 historical ones, something that has never happened before. The curatorship aimed at revealing an “other” modernism, the one developed in and from the South.

-

Julia Isídrez. 60th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere. Photo by: Marco Zorzanello.

-

Julia Isídrez. 60th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere. Photo by: Marco Zorzanello.

-

Madre e hija: Juana Marta Rodas y Julia Isídrez. Cortesía CAV/Museo del Barro.

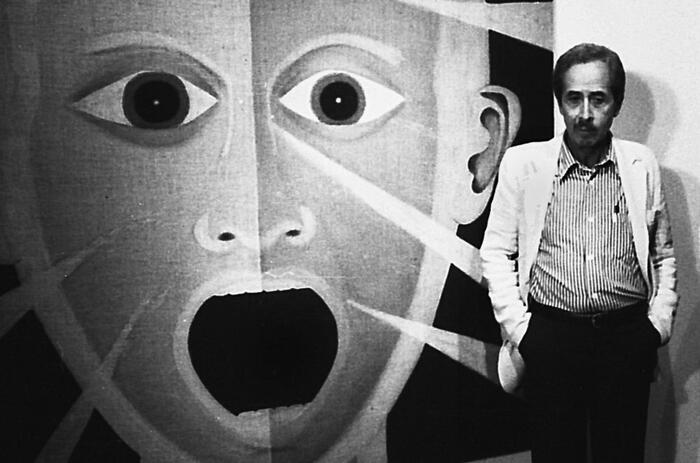

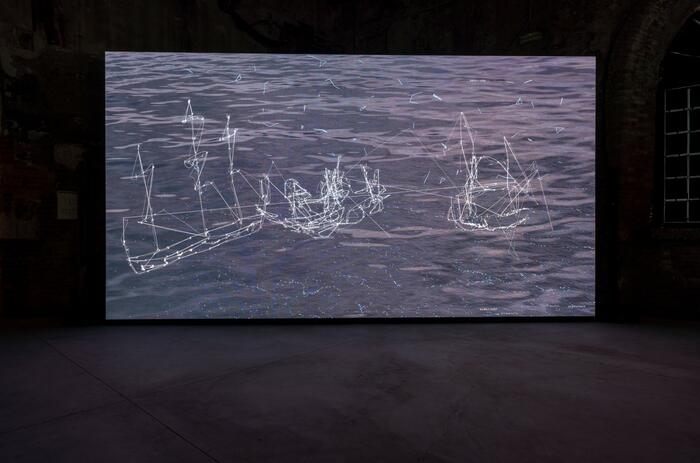

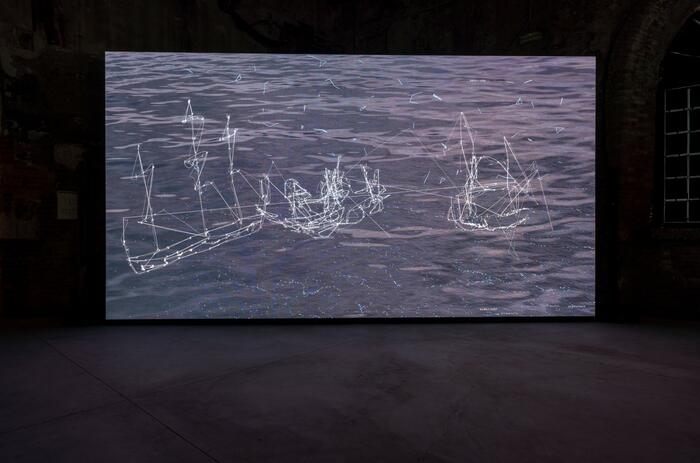

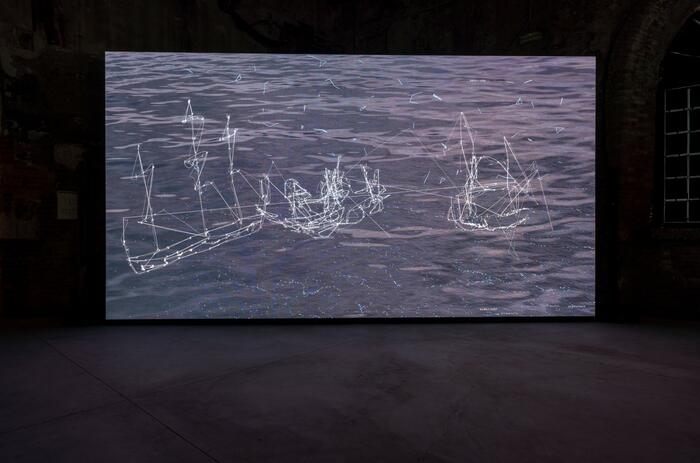

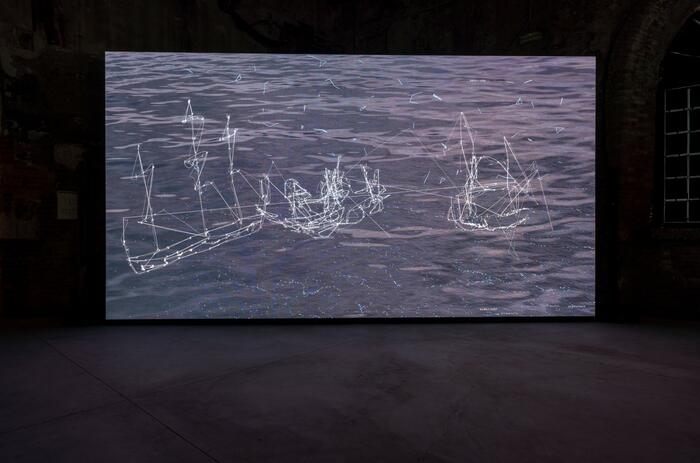

No one doubts that this edition marks a turning point in the centennial biennial, both for the main exhibition displayed at Giardini and Arsenale, as well as for the national proposals, many of great quality and poetry. The most glamorous and seductive appointment of the global art scene, the one that triggers careers and quotations, has been invaded, contaminated, exceeded. The curator's decolonial vocation - perceptible in his impeccable previous proposals - takes on board the displaced of the world in an epic voyage that appeals to the shipwreck and may even evoke Le radeau de la Méduse.

However, and in the face of the sullen North-Atlantic gaze, here we are from the Global South - an expression that more than geographical coordinates indicate a political position -, all together, in this opportunity that may never be repeated. Yes, all of us together, mixed and even messy, the past and the future at the same table, putting furious colors to pain, weaving links like threads in a tapestry, disregarding canons and discovering each other. This biennial bears the mark of excess. And no wonder. More than two thirds of the world are here, exposing their conflicts, stories and fictions, or reflecting on their origins. That is why, at times, it is not only difficult to understand the narrative, but also to visualize the broad horizon that this overflowing edition poses. A discursive overflow that is announced from the very beginning in the iconic façade of the main pavilion of the Giardini -proudly displaying the logo of La Biennale- completely intervened by the Brazilian indigenous collective MAHKU (Movimento dos artistas Huni Kuin). A political gesture that could be naively interpreted as festive, folkloric or complacent, when in fact it is about human tragedy narrated in the visual codes of a culture.

-

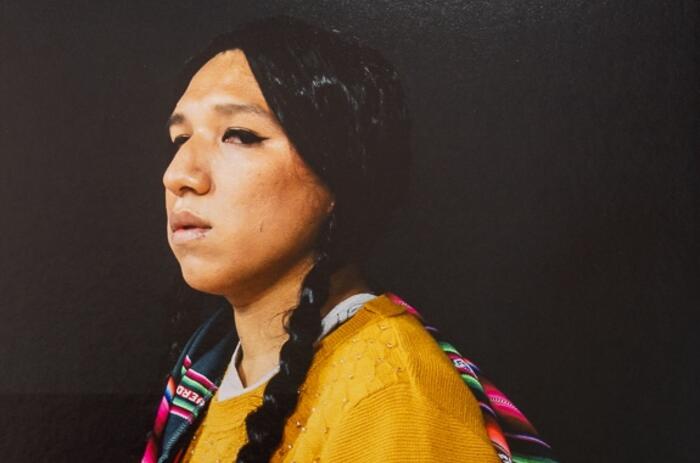

Photo by Matteo DeMayda.

-

Photo by Matteo DeMayda.

In an Italy shaken by nationalism and xenophobia, filling the Venice Biennale with “foreigners” and outsiders sounds even reckless. Pedrosa is encouraged. It is in this context that Julia Isidrez's work can be seen for what it is: a direct connection with life. This is how her cassava and coconut worms, her centipedes, her anteaters, her lobisons and the many hollows that shelter a corporal and sensitive memory of women of the people were born. A centuries-old wisdom transmitted from generation to generation.

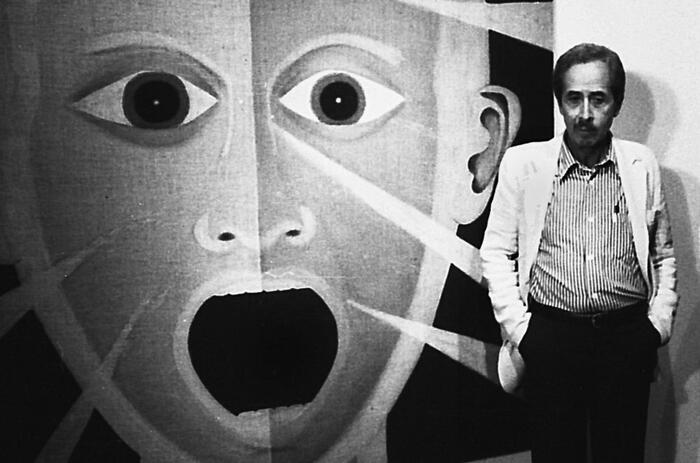

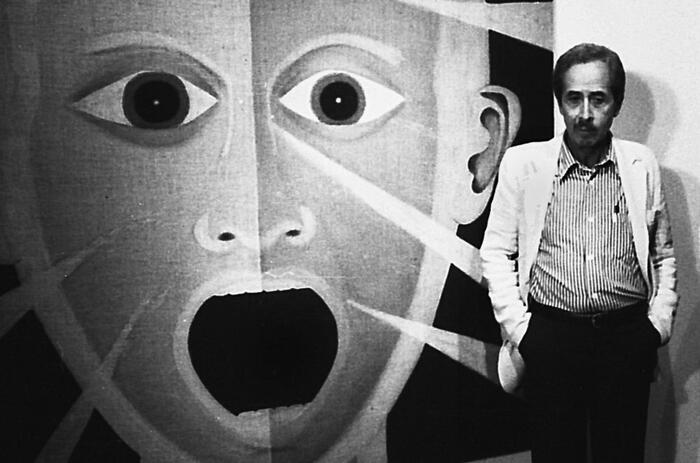

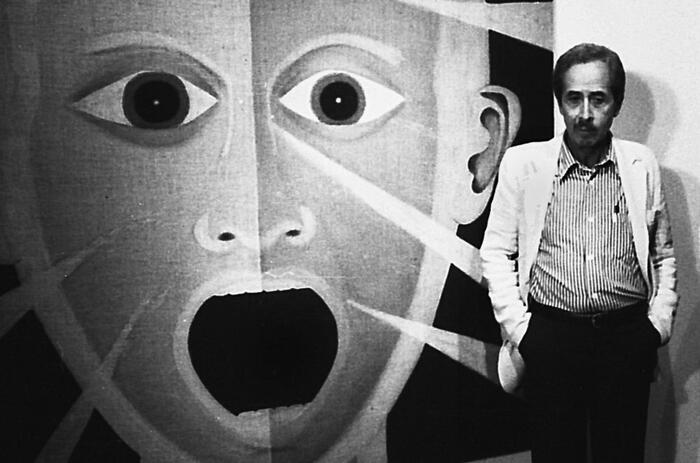

Finally, the most frequently asked questions in recent days: Isn't this a biennial designed for spectators from the center? Doesn't it resemble a cabinet of curiosities or a fair of oddities? Beyond the criticisms, I think the biennial canon has been destabilized and that irritates. For a moment, this biennial turns the map upside down, as Torres Garcia did. Perhaps the most productive thing to do is to read it as a great book of the world, with an open spirit and without prejudices.

Related Topics

May interest you

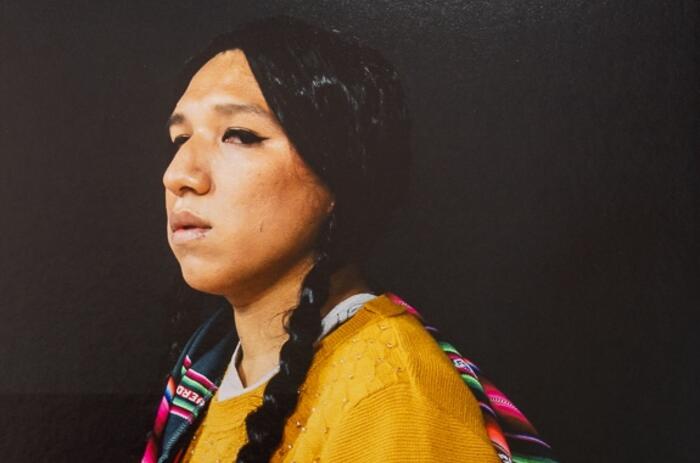

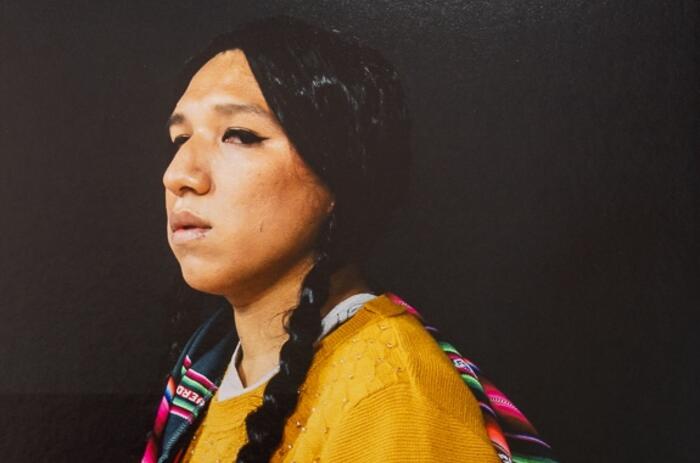

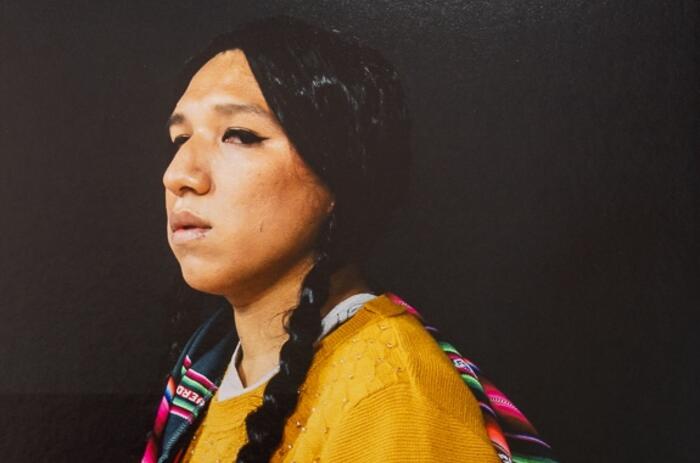

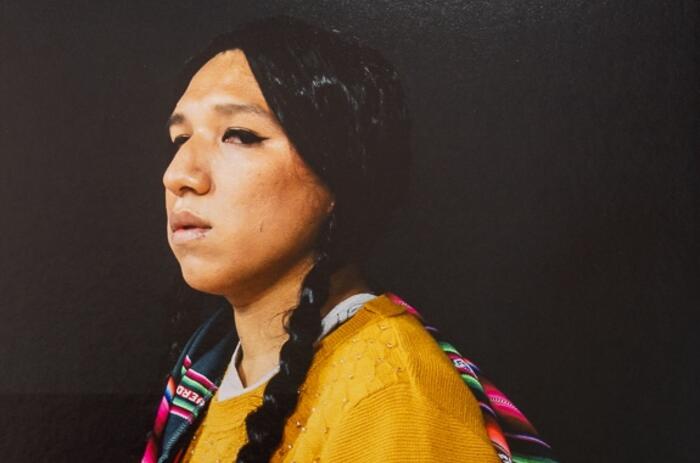

Argentine artist La Chola Poblete received a special mention at the Venice Biennale 2024, selected together with artist Samia Halaby.

LA CHOLA POBLETE WAS AWARDED AT THE VENICE BIENNIAL

Argentine artist La Chola Poblete received a special mention at the Venice Biennale 2024, selected together with artist Samia Halaby.

Argentine artist La Chola Poblete received a special mention at the Venice Biennale 2024, selected together with artist Samia Halaby.

LA CHOLA POBLETE WAS AWARDED AT THE VENICE BIENNIAL

Argentine artist La Chola Poblete received a special mention at the Venice Biennale 2024, selected together with artist Samia Halaby.

Tania Pardo (Madrid, Spain, 1976) is the new Director of the Museo Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo (CA2M Museum), the museum of contemporary art of the Community of Madrid. Pardo's career until her recent appointment has been built on a detailed work of promotion and visibility of emerging art through the curatorial actions she has developed in numerous Spanish institutions.

INTERVIEW WITH TANIA PARDO, NEW DIRECTOR OF CA2M MUSEUM

Tania Pardo (Madrid, Spain, 1976) is the new Director of the Museo Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo (CA2M Museum), the museum of contemporary art of the Community of Madrid. Pardo's career until her recent appointment has been built on a detailed work of promotion and visibility of emerging art through the curatorial actions she has developed in numerous Spanish institutions.

Art fairs and biennials inhabit the same artistic universe but serve distinct purposes. The former primarily functions as commercial hubs where artworks are bought and sold, whereas biennials act as global stages, celebrating the rich diversity of contemporary art.

BIENNALE UNVEILED: GLOBAL EXHIBITION AND COMMERCE OPPORTUNITIES.

Art fairs and biennials inhabit the same artistic universe but serve distinct purposes. The former primarily functions as commercial hubs where artworks are bought and sold, whereas biennials act as global stages, celebrating the rich diversity of contemporary art.

The Russian Venice Biennale pavilion is hosting a group exhibition of artists from South America organized by Bolivia’s Ministry of Cultures, Decolonization and Depatriarchalizing.

RUSSIA’S VENICE BIENNALE PAVILION WILL HOST BOLIVIA’S PROPOSAL

The Russian Venice Biennale pavilion is hosting a group exhibition of artists from South America organized by Bolivia’s Ministry of Cultures, Decolonization and Depatriarchalizing.

Frieze New York 2024 returns to The Shed in New York with a new curator for Focus, more than 60 galleries from 25 countries and an extensive program of events and activations. This year’s edition will be held from May 1-5.

FRIEZE NEW YORK 2024: CELEBRATING ART AND THE CITY

Frieze New York 2024 returns to The Shed in New York with a new curator for Focus, more than 60 galleries from 25 countries and an extensive program of events and activations. This year’s edition will be held from May 1-5.

The Fundação Biennale de São Paulo announced that Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung will be the chief curator of the 36th São Paulo Biennale, to be held during the second half of 2025.

BONAVENTURE SOH BEJENG NDIKUNG WILL BE THE CHIEF CURATOR OF THE 36TH SÃO PAULO BIENNALE

The Fundação Biennale de São Paulo announced that Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung will be the chief curator of the 36th São Paulo Biennale, to be held during the second half of 2025.

Pinta PArC is the official contemporary art fair in Peru. In its 11th edition –from April 25 to 28– the fair presents an experimental and ambitious program, with unique curatorial projects.

CURATORIAL PROJECTS AT PINTA PArC 2024

Pinta PArC is the official contemporary art fair in Peru. In its 11th edition –from April 25 to 28– the fair presents an experimental and ambitious program, with unique curatorial projects.

La Chola Poblete, Argentine artist and LGBTQ+ rights activist, draws confrontation between historical stereotypes and contemporary visual languages. Her colourful works in diverse media disrupt prevailing power structures and celebrate the rich culture of South American Indigenous peoples. Titled after her hometown, Guaymallén is La Chola’s solo exhibition at PalaisPopulaire, curated by Britta Färber, head of Deutsche Bank’s international art and culture program.

LA CHOLA POBLETE EXHIBITS VIRGINS, COLONIALISM AND EROTICA IN GUAYMALLÉN

La Chola Poblete, Argentine artist and LGBTQ+ rights activist, draws confrontation between historical stereotypes and contemporary visual languages. Her colourful works in diverse media disrupt prevailing power structures and celebrate the rich culture of South American Indigenous peoples. Titled after her hometown, Guaymallén is La Chola’s solo exhibition at PalaisPopulaire, curated by Britta Färber, head of Deutsche Bank’s international art and culture program.

With the opening of Frieze NY last Wednesday, the NY Contemporary sales season has kicked off (if it ever truly stops!). From now until mid-May, it's a whirlwind of fairs and gallery openings, culminating in the grand auctions. May is a crucial time for the US art market calendar and the results will have global repercussion for the remainder of the year.

FRIEZE NEW YORK 2024 – A VIEW FROM THE FLOOR

With the opening of Frieze NY last Wednesday, the NY Contemporary sales season has kicked off (if it ever truly stops!). From now until mid-May, it's a whirlwind of fairs and gallery openings, culminating in the grand auctions. May is a crucial time for the US art market calendar and the results will have global repercussion for the remainder of the year.

El Museo del Barrio presented the exhibition Amalia Mesa-Bains: Archaeology of Memory, the first retrospective exhibition by the pioneering artist, curator, and theorist. Born in 1943 to a Mexican immigrant family, Mesa-Bains has been a leading figure in Chicanx art for nearly half a century.

AMALIA MESA-BAINS: ARCHAEOLOGY OF MEMORY

El Museo del Barrio presented the exhibition Amalia Mesa-Bains: Archaeology of Memory, the first retrospective exhibition by the pioneering artist, curator, and theorist. Born in 1943 to a Mexican immigrant family, Mesa-Bains has been a leading figure in Chicanx art for nearly half a century.

Leonora Carrington’s painting "Les Distractions de Dagobert" (1945), valued between $12 to $18 million, is generating considerable excitement as it heads to auction at Sotheby's this May. Having been in an American collection since 1995, its upcoming sale not only reflects the escalating market demand for Carrington's pieces but also underscores the rising interest in female Surrealist artists.

LEONORA CARRINGTON'S BID FOR LATIN AMERICAN RECORD

Leonora Carrington’s painting "Les Distractions de Dagobert" (1945), valued between $12 to $18 million, is generating considerable excitement as it heads to auction at Sotheby's this May. Having been in an American collection since 1995, its upcoming sale not only reflects the escalating market demand for Carrington's pieces but also underscores the rising interest in female Surrealist artists.

Malta’s pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale presented artist Matthew Attard’s solo project, I Will Follow the Ship. Curated by Elyse Tonna and Sara Dolfi Agostini.

MALTA PAVILION AT THE VENICE BIENNALE 2024

Malta’s pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale presented artist Matthew Attard’s solo project, I Will Follow the Ship. Curated by Elyse Tonna and Sara Dolfi Agostini.

A Comparative Dialogue Act, a project by the Luxembourgish artist Andrea Mancini and the multidisciplinary collective Every Island is representing the Luxembourg Pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale.

ANDREA MANCINI & EVERY ISLAND: LUXEMBOURG PAVILION AT THE VENICE BIENNALE

A Comparative Dialogue Act, a project by the Luxembourgish artist Andrea Mancini and the multidisciplinary collective Every Island is representing the Luxembourg Pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale.

On Thursday, April 18, 2024, the exhibition project Trámites, a duo-show by visual artists Yéssica Montero (1998, Dominican Republic) and Ernesto Rivera (1983, Dominican Republic), opened at the independent spaces of La Sociedad, in Santo Domingo.

TRÁMITES: PROTOCOLS AND STRATEGIES TO EXIST IN EMERGENCIES

On Thursday, April 18, 2024, the exhibition project Trámites, a duo-show by visual artists Yéssica Montero (1998, Dominican Republic) and Ernesto Rivera (1983, Dominican Republic), opened at the independent spaces of La Sociedad, in Santo Domingo.

Commissioned by Facundo de Almeida and curated by Elisa Valerio, the national pavilion of Uruguay presents the work of Eduardo Cardozo with the project Latent.

THE PAVILION OF URUGUAY AT THE 60TH VENICE BIENNALE

Commissioned by Facundo de Almeida and curated by Elisa Valerio, the national pavilion of Uruguay presents the work of Eduardo Cardozo with the project Latent.

The jury of the IV Mediterranean Albert Camus Prize –composed of Javier Gomá, who acts as its president, and N’Goné Fall, Miquel Molina, José Luis Pérez Pont and Anne Prouteau– decided to unanimously award Alfredo Jaar the 2024 edition prize.

ALFREDO JAAR WINS 2024 MEDITERRANEAN ALBERT CAMUS PRIZE

The jury of the IV Mediterranean Albert Camus Prize –composed of Javier Gomá, who acts as its president, and N’Goné Fall, Miquel Molina, José Luis Pérez Pont and Anne Prouteau– decided to unanimously award Alfredo Jaar the 2024 edition prize.

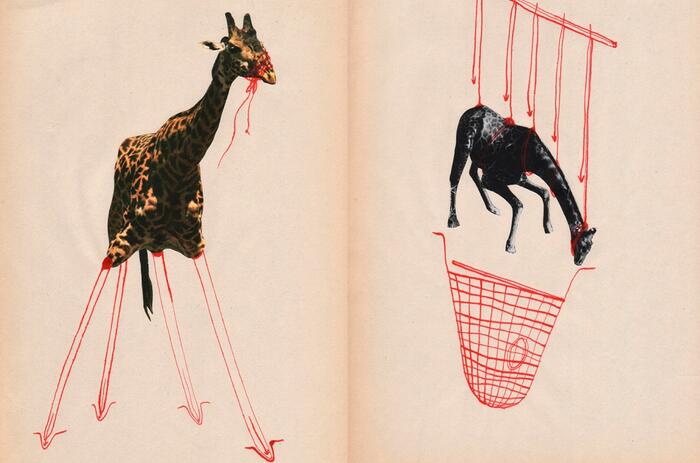

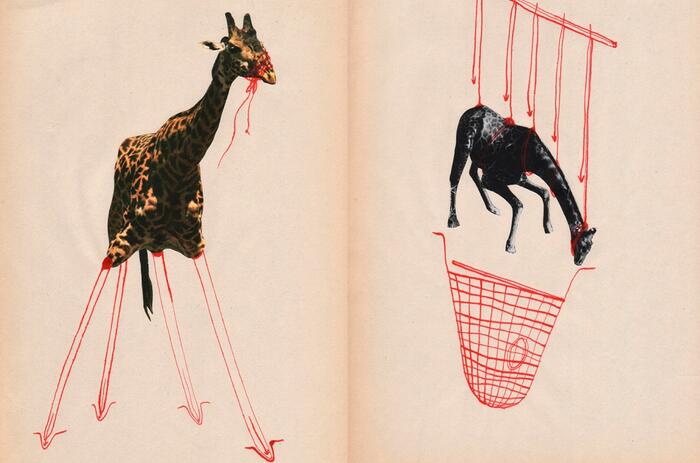

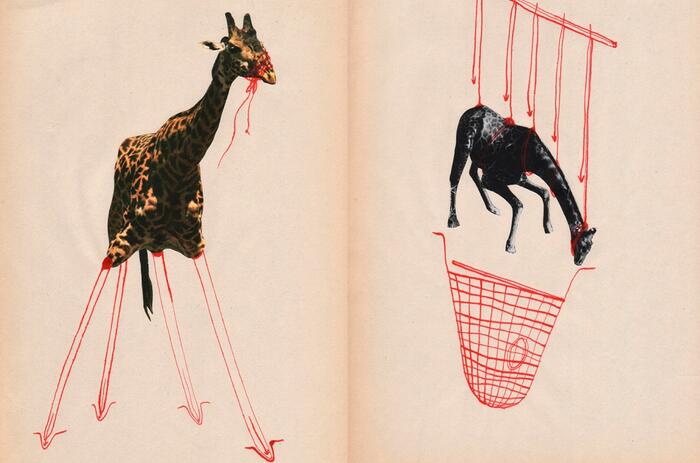

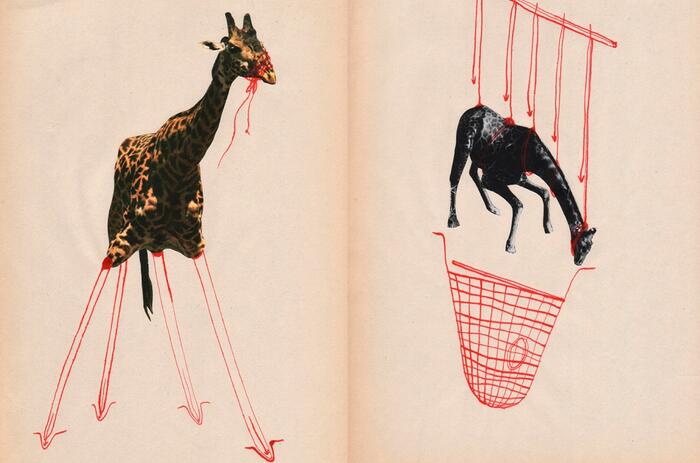

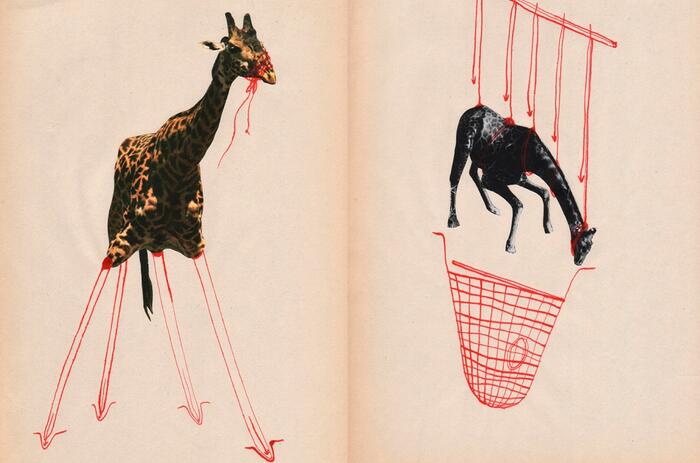

The heart of a giraffe in captivity is twelve kilos lighter tells the story of Lenka the giraffe, drawing on the history of Czechoslovakia’s acquisition of animals from the Global South. Interpreted through contemporary ecological and decolonial perspectives, Eva Kotátková’s project of the Czech and Slovak Republic Pavilion at the Venice Biennale builds a space for imagining a different way of relating to nature.

THE VENICE BIENNALE: CZECH AND SLOVAK REPUBLIC PAVILION

The heart of a giraffe in captivity is twelve kilos lighter tells the story of Lenka the giraffe, drawing on the history of Czechoslovakia’s acquisition of animals from the Global South. Interpreted through contemporary ecological and decolonial perspectives, Eva Kotátková’s project of the Czech and Slovak Republic Pavilion at the Venice Biennale builds a space for imagining a different way of relating to nature.

The International Association of Art Critics in Paraguay (AICA-Py) awarded the AICA 2023 Prize to the exhibition Cuadernos de campo (Field Notebooks) by Fidel Fernández, curated by Adriana Almada and exhibited during Pinta Sud 2023 at the Arte Actual gallery in Asuncion.

FIDEL FERNÁNDEZ WINS AICA PARAGUAY 2023 AWARD

The International Association of Art Critics in Paraguay (AICA-Py) awarded the AICA 2023 Prize to the exhibition Cuadernos de campo (Field Notebooks) by Fidel Fernández, curated by Adriana Almada and exhibited during Pinta Sud 2023 at the Arte Actual gallery in Asuncion.

Pinta Sud | ASU presents the third and final edition of Asunción’s Art Week, taking place from August 5-11, 2024. The event will feature art exhibitions, events, and various activities free and open to the public, offering seven days of artistic celebration throughout the city.

ASUNCIÓN IN THE SPOTLIGHT: LAST EDITION OF PINTA SUD

Pinta Sud | ASU presents the third and final edition of Asunción’s Art Week, taking place from August 5-11, 2024. The event will feature art exhibitions, events, and various activities free and open to the public, offering seven days of artistic celebration throughout the city.

Argentine artist La Chola Poblete received a special mention at the Venice Biennale 2024, selected together with artist Samia Halaby.

LA CHOLA POBLETE WAS AWARDED AT THE VENICE BIENNIAL

Argentine artist La Chola Poblete received a special mention at the Venice Biennale 2024, selected together with artist Samia Halaby.

Tania Pardo (Madrid, Spain, 1976) is the new Director of the Museo Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo (CA2M Museum), the museum of contemporary art of the Community of Madrid. Pardo's career until her recent appointment has been built on a detailed work of promotion and visibility of emerging art through the curatorial actions she has developed in numerous Spanish institutions.

INTERVIEW WITH TANIA PARDO, NEW DIRECTOR OF CA2M MUSEUM

Tania Pardo (Madrid, Spain, 1976) is the new Director of the Museo Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo (CA2M Museum), the museum of contemporary art of the Community of Madrid. Pardo's career until her recent appointment has been built on a detailed work of promotion and visibility of emerging art through the curatorial actions she has developed in numerous Spanish institutions.

Art fairs and biennials inhabit the same artistic universe but serve distinct purposes. The former primarily functions as commercial hubs where artworks are bought and sold, whereas biennials act as global stages, celebrating the rich diversity of contemporary art.

BIENNALE UNVEILED: GLOBAL EXHIBITION AND COMMERCE OPPORTUNITIES.

Art fairs and biennials inhabit the same artistic universe but serve distinct purposes. The former primarily functions as commercial hubs where artworks are bought and sold, whereas biennials act as global stages, celebrating the rich diversity of contemporary art.

The Russian Venice Biennale pavilion is hosting a group exhibition of artists from South America organized by Bolivia’s Ministry of Cultures, Decolonization and Depatriarchalizing.

RUSSIA’S VENICE BIENNALE PAVILION WILL HOST BOLIVIA’S PROPOSAL

The Russian Venice Biennale pavilion is hosting a group exhibition of artists from South America organized by Bolivia’s Ministry of Cultures, Decolonization and Depatriarchalizing.

Frieze New York 2024 returns to The Shed in New York with a new curator for Focus, more than 60 galleries from 25 countries and an extensive program of events and activations. This year’s edition will be held from May 1-5.

FRIEZE NEW YORK 2024: CELEBRATING ART AND THE CITY

Frieze New York 2024 returns to The Shed in New York with a new curator for Focus, more than 60 galleries from 25 countries and an extensive program of events and activations. This year’s edition will be held from May 1-5.

The Fundação Biennale de São Paulo announced that Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung will be the chief curator of the 36th São Paulo Biennale, to be held during the second half of 2025.

BONAVENTURE SOH BEJENG NDIKUNG WILL BE THE CHIEF CURATOR OF THE 36TH SÃO PAULO BIENNALE

The Fundação Biennale de São Paulo announced that Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung will be the chief curator of the 36th São Paulo Biennale, to be held during the second half of 2025.

Pinta PArC is the official contemporary art fair in Peru. In its 11th edition –from April 25 to 28– the fair presents an experimental and ambitious program, with unique curatorial projects.

CURATORIAL PROJECTS AT PINTA PArC 2024

Pinta PArC is the official contemporary art fair in Peru. In its 11th edition –from April 25 to 28– the fair presents an experimental and ambitious program, with unique curatorial projects.

La Chola Poblete, Argentine artist and LGBTQ+ rights activist, draws confrontation between historical stereotypes and contemporary visual languages. Her colourful works in diverse media disrupt prevailing power structures and celebrate the rich culture of South American Indigenous peoples. Titled after her hometown, Guaymallén is La Chola’s solo exhibition at PalaisPopulaire, curated by Britta Färber, head of Deutsche Bank’s international art and culture program.

LA CHOLA POBLETE EXHIBITS VIRGINS, COLONIALISM AND EROTICA IN GUAYMALLÉN

La Chola Poblete, Argentine artist and LGBTQ+ rights activist, draws confrontation between historical stereotypes and contemporary visual languages. Her colourful works in diverse media disrupt prevailing power structures and celebrate the rich culture of South American Indigenous peoples. Titled after her hometown, Guaymallén is La Chola’s solo exhibition at PalaisPopulaire, curated by Britta Färber, head of Deutsche Bank’s international art and culture program.

With the opening of Frieze NY last Wednesday, the NY Contemporary sales season has kicked off (if it ever truly stops!). From now until mid-May, it's a whirlwind of fairs and gallery openings, culminating in the grand auctions. May is a crucial time for the US art market calendar and the results will have global repercussion for the remainder of the year.

FRIEZE NEW YORK 2024 – A VIEW FROM THE FLOOR

With the opening of Frieze NY last Wednesday, the NY Contemporary sales season has kicked off (if it ever truly stops!). From now until mid-May, it's a whirlwind of fairs and gallery openings, culminating in the grand auctions. May is a crucial time for the US art market calendar and the results will have global repercussion for the remainder of the year.

El Museo del Barrio presented the exhibition Amalia Mesa-Bains: Archaeology of Memory, the first retrospective exhibition by the pioneering artist, curator, and theorist. Born in 1943 to a Mexican immigrant family, Mesa-Bains has been a leading figure in Chicanx art for nearly half a century.

AMALIA MESA-BAINS: ARCHAEOLOGY OF MEMORY

El Museo del Barrio presented the exhibition Amalia Mesa-Bains: Archaeology of Memory, the first retrospective exhibition by the pioneering artist, curator, and theorist. Born in 1943 to a Mexican immigrant family, Mesa-Bains has been a leading figure in Chicanx art for nearly half a century.

Leonora Carrington’s painting "Les Distractions de Dagobert" (1945), valued between $12 to $18 million, is generating considerable excitement as it heads to auction at Sotheby's this May. Having been in an American collection since 1995, its upcoming sale not only reflects the escalating market demand for Carrington's pieces but also underscores the rising interest in female Surrealist artists.

LEONORA CARRINGTON'S BID FOR LATIN AMERICAN RECORD

Leonora Carrington’s painting "Les Distractions de Dagobert" (1945), valued between $12 to $18 million, is generating considerable excitement as it heads to auction at Sotheby's this May. Having been in an American collection since 1995, its upcoming sale not only reflects the escalating market demand for Carrington's pieces but also underscores the rising interest in female Surrealist artists.

Malta’s pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale presented artist Matthew Attard’s solo project, I Will Follow the Ship. Curated by Elyse Tonna and Sara Dolfi Agostini.

MALTA PAVILION AT THE VENICE BIENNALE 2024

Malta’s pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale presented artist Matthew Attard’s solo project, I Will Follow the Ship. Curated by Elyse Tonna and Sara Dolfi Agostini.

A Comparative Dialogue Act, a project by the Luxembourgish artist Andrea Mancini and the multidisciplinary collective Every Island is representing the Luxembourg Pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale.

ANDREA MANCINI & EVERY ISLAND: LUXEMBOURG PAVILION AT THE VENICE BIENNALE

A Comparative Dialogue Act, a project by the Luxembourgish artist Andrea Mancini and the multidisciplinary collective Every Island is representing the Luxembourg Pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale.

On Thursday, April 18, 2024, the exhibition project Trámites, a duo-show by visual artists Yéssica Montero (1998, Dominican Republic) and Ernesto Rivera (1983, Dominican Republic), opened at the independent spaces of La Sociedad, in Santo Domingo.

TRÁMITES: PROTOCOLS AND STRATEGIES TO EXIST IN EMERGENCIES

On Thursday, April 18, 2024, the exhibition project Trámites, a duo-show by visual artists Yéssica Montero (1998, Dominican Republic) and Ernesto Rivera (1983, Dominican Republic), opened at the independent spaces of La Sociedad, in Santo Domingo.

Commissioned by Facundo de Almeida and curated by Elisa Valerio, the national pavilion of Uruguay presents the work of Eduardo Cardozo with the project Latent.

THE PAVILION OF URUGUAY AT THE 60TH VENICE BIENNALE

Commissioned by Facundo de Almeida and curated by Elisa Valerio, the national pavilion of Uruguay presents the work of Eduardo Cardozo with the project Latent.

The jury of the IV Mediterranean Albert Camus Prize –composed of Javier Gomá, who acts as its president, and N’Goné Fall, Miquel Molina, José Luis Pérez Pont and Anne Prouteau– decided to unanimously award Alfredo Jaar the 2024 edition prize.

ALFREDO JAAR WINS 2024 MEDITERRANEAN ALBERT CAMUS PRIZE

The jury of the IV Mediterranean Albert Camus Prize –composed of Javier Gomá, who acts as its president, and N’Goné Fall, Miquel Molina, José Luis Pérez Pont and Anne Prouteau– decided to unanimously award Alfredo Jaar the 2024 edition prize.

The heart of a giraffe in captivity is twelve kilos lighter tells the story of Lenka the giraffe, drawing on the history of Czechoslovakia’s acquisition of animals from the Global South. Interpreted through contemporary ecological and decolonial perspectives, Eva Kotátková’s project of the Czech and Slovak Republic Pavilion at the Venice Biennale builds a space for imagining a different way of relating to nature.

THE VENICE BIENNALE: CZECH AND SLOVAK REPUBLIC PAVILION

The heart of a giraffe in captivity is twelve kilos lighter tells the story of Lenka the giraffe, drawing on the history of Czechoslovakia’s acquisition of animals from the Global South. Interpreted through contemporary ecological and decolonial perspectives, Eva Kotátková’s project of the Czech and Slovak Republic Pavilion at the Venice Biennale builds a space for imagining a different way of relating to nature.

The International Association of Art Critics in Paraguay (AICA-Py) awarded the AICA 2023 Prize to the exhibition Cuadernos de campo (Field Notebooks) by Fidel Fernández, curated by Adriana Almada and exhibited during Pinta Sud 2023 at the Arte Actual gallery in Asuncion.

FIDEL FERNÁNDEZ WINS AICA PARAGUAY 2023 AWARD

The International Association of Art Critics in Paraguay (AICA-Py) awarded the AICA 2023 Prize to the exhibition Cuadernos de campo (Field Notebooks) by Fidel Fernández, curated by Adriana Almada and exhibited during Pinta Sud 2023 at the Arte Actual gallery in Asuncion.

Pinta Sud | ASU presents the third and final edition of Asunción’s Art Week, taking place from August 5-11, 2024. The event will feature art exhibitions, events, and various activities free and open to the public, offering seven days of artistic celebration throughout the city.

ASUNCIÓN IN THE SPOTLIGHT: LAST EDITION OF PINTA SUD

Pinta Sud | ASU presents the third and final edition of Asunción’s Art Week, taking place from August 5-11, 2024. The event will feature art exhibitions, events, and various activities free and open to the public, offering seven days of artistic celebration throughout the city.

Argentine artist La Chola Poblete received a special mention at the Venice Biennale 2024, selected together with artist Samia Halaby.

LA CHOLA POBLETE WAS AWARDED AT THE VENICE BIENNIAL

Argentine artist La Chola Poblete received a special mention at the Venice Biennale 2024, selected together with artist Samia Halaby.

Tania Pardo (Madrid, Spain, 1976) is the new Director of the Museo Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo (CA2M Museum), the museum of contemporary art of the Community of Madrid. Pardo's career until her recent appointment has been built on a detailed work of promotion and visibility of emerging art through the curatorial actions she has developed in numerous Spanish institutions.

INTERVIEW WITH TANIA PARDO, NEW DIRECTOR OF CA2M MUSEUM

Tania Pardo (Madrid, Spain, 1976) is the new Director of the Museo Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo (CA2M Museum), the museum of contemporary art of the Community of Madrid. Pardo's career until her recent appointment has been built on a detailed work of promotion and visibility of emerging art through the curatorial actions she has developed in numerous Spanish institutions.

Art fairs and biennials inhabit the same artistic universe but serve distinct purposes. The former primarily functions as commercial hubs where artworks are bought and sold, whereas biennials act as global stages, celebrating the rich diversity of contemporary art.

BIENNALE UNVEILED: GLOBAL EXHIBITION AND COMMERCE OPPORTUNITIES.

Art fairs and biennials inhabit the same artistic universe but serve distinct purposes. The former primarily functions as commercial hubs where artworks are bought and sold, whereas biennials act as global stages, celebrating the rich diversity of contemporary art.

The Russian Venice Biennale pavilion is hosting a group exhibition of artists from South America organized by Bolivia’s Ministry of Cultures, Decolonization and Depatriarchalizing.

RUSSIA’S VENICE BIENNALE PAVILION WILL HOST BOLIVIA’S PROPOSAL

The Russian Venice Biennale pavilion is hosting a group exhibition of artists from South America organized by Bolivia’s Ministry of Cultures, Decolonization and Depatriarchalizing.

Frieze New York 2024 returns to The Shed in New York with a new curator for Focus, more than 60 galleries from 25 countries and an extensive program of events and activations. This year’s edition will be held from May 1-5.

FRIEZE NEW YORK 2024: CELEBRATING ART AND THE CITY

Frieze New York 2024 returns to The Shed in New York with a new curator for Focus, more than 60 galleries from 25 countries and an extensive program of events and activations. This year’s edition will be held from May 1-5.

The Fundação Biennale de São Paulo announced that Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung will be the chief curator of the 36th São Paulo Biennale, to be held during the second half of 2025.

BONAVENTURE SOH BEJENG NDIKUNG WILL BE THE CHIEF CURATOR OF THE 36TH SÃO PAULO BIENNALE

The Fundação Biennale de São Paulo announced that Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung will be the chief curator of the 36th São Paulo Biennale, to be held during the second half of 2025.

Pinta PArC is the official contemporary art fair in Peru. In its 11th edition –from April 25 to 28– the fair presents an experimental and ambitious program, with unique curatorial projects.

CURATORIAL PROJECTS AT PINTA PArC 2024

Pinta PArC is the official contemporary art fair in Peru. In its 11th edition –from April 25 to 28– the fair presents an experimental and ambitious program, with unique curatorial projects.

La Chola Poblete, Argentine artist and LGBTQ+ rights activist, draws confrontation between historical stereotypes and contemporary visual languages. Her colourful works in diverse media disrupt prevailing power structures and celebrate the rich culture of South American Indigenous peoples. Titled after her hometown, Guaymallén is La Chola’s solo exhibition at PalaisPopulaire, curated by Britta Färber, head of Deutsche Bank’s international art and culture program.

LA CHOLA POBLETE EXHIBITS VIRGINS, COLONIALISM AND EROTICA IN GUAYMALLÉN

La Chola Poblete, Argentine artist and LGBTQ+ rights activist, draws confrontation between historical stereotypes and contemporary visual languages. Her colourful works in diverse media disrupt prevailing power structures and celebrate the rich culture of South American Indigenous peoples. Titled after her hometown, Guaymallén is La Chola’s solo exhibition at PalaisPopulaire, curated by Britta Färber, head of Deutsche Bank’s international art and culture program.

With the opening of Frieze NY last Wednesday, the NY Contemporary sales season has kicked off (if it ever truly stops!). From now until mid-May, it's a whirlwind of fairs and gallery openings, culminating in the grand auctions. May is a crucial time for the US art market calendar and the results will have global repercussion for the remainder of the year.

FRIEZE NEW YORK 2024 – A VIEW FROM THE FLOOR

With the opening of Frieze NY last Wednesday, the NY Contemporary sales season has kicked off (if it ever truly stops!). From now until mid-May, it's a whirlwind of fairs and gallery openings, culminating in the grand auctions. May is a crucial time for the US art market calendar and the results will have global repercussion for the remainder of the year.

El Museo del Barrio presented the exhibition Amalia Mesa-Bains: Archaeology of Memory, the first retrospective exhibition by the pioneering artist, curator, and theorist. Born in 1943 to a Mexican immigrant family, Mesa-Bains has been a leading figure in Chicanx art for nearly half a century.

AMALIA MESA-BAINS: ARCHAEOLOGY OF MEMORY

El Museo del Barrio presented the exhibition Amalia Mesa-Bains: Archaeology of Memory, the first retrospective exhibition by the pioneering artist, curator, and theorist. Born in 1943 to a Mexican immigrant family, Mesa-Bains has been a leading figure in Chicanx art for nearly half a century.

Leonora Carrington’s painting "Les Distractions de Dagobert" (1945), valued between $12 to $18 million, is generating considerable excitement as it heads to auction at Sotheby's this May. Having been in an American collection since 1995, its upcoming sale not only reflects the escalating market demand for Carrington's pieces but also underscores the rising interest in female Surrealist artists.

LEONORA CARRINGTON'S BID FOR LATIN AMERICAN RECORD

Leonora Carrington’s painting "Les Distractions de Dagobert" (1945), valued between $12 to $18 million, is generating considerable excitement as it heads to auction at Sotheby's this May. Having been in an American collection since 1995, its upcoming sale not only reflects the escalating market demand for Carrington's pieces but also underscores the rising interest in female Surrealist artists.

Malta’s pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale presented artist Matthew Attard’s solo project, I Will Follow the Ship. Curated by Elyse Tonna and Sara Dolfi Agostini.

MALTA PAVILION AT THE VENICE BIENNALE 2024

Malta’s pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale presented artist Matthew Attard’s solo project, I Will Follow the Ship. Curated by Elyse Tonna and Sara Dolfi Agostini.

A Comparative Dialogue Act, a project by the Luxembourgish artist Andrea Mancini and the multidisciplinary collective Every Island is representing the Luxembourg Pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale.

ANDREA MANCINI & EVERY ISLAND: LUXEMBOURG PAVILION AT THE VENICE BIENNALE

A Comparative Dialogue Act, a project by the Luxembourgish artist Andrea Mancini and the multidisciplinary collective Every Island is representing the Luxembourg Pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale.

On Thursday, April 18, 2024, the exhibition project Trámites, a duo-show by visual artists Yéssica Montero (1998, Dominican Republic) and Ernesto Rivera (1983, Dominican Republic), opened at the independent spaces of La Sociedad, in Santo Domingo.

TRÁMITES: PROTOCOLS AND STRATEGIES TO EXIST IN EMERGENCIES

On Thursday, April 18, 2024, the exhibition project Trámites, a duo-show by visual artists Yéssica Montero (1998, Dominican Republic) and Ernesto Rivera (1983, Dominican Republic), opened at the independent spaces of La Sociedad, in Santo Domingo.

Commissioned by Facundo de Almeida and curated by Elisa Valerio, the national pavilion of Uruguay presents the work of Eduardo Cardozo with the project Latent.

THE PAVILION OF URUGUAY AT THE 60TH VENICE BIENNALE

Commissioned by Facundo de Almeida and curated by Elisa Valerio, the national pavilion of Uruguay presents the work of Eduardo Cardozo with the project Latent.

The jury of the IV Mediterranean Albert Camus Prize –composed of Javier Gomá, who acts as its president, and N’Goné Fall, Miquel Molina, José Luis Pérez Pont and Anne Prouteau– decided to unanimously award Alfredo Jaar the 2024 edition prize.

ALFREDO JAAR WINS 2024 MEDITERRANEAN ALBERT CAMUS PRIZE

The jury of the IV Mediterranean Albert Camus Prize –composed of Javier Gomá, who acts as its president, and N’Goné Fall, Miquel Molina, José Luis Pérez Pont and Anne Prouteau– decided to unanimously award Alfredo Jaar the 2024 edition prize.

The heart of a giraffe in captivity is twelve kilos lighter tells the story of Lenka the giraffe, drawing on the history of Czechoslovakia’s acquisition of animals from the Global South. Interpreted through contemporary ecological and decolonial perspectives, Eva Kotátková’s project of the Czech and Slovak Republic Pavilion at the Venice Biennale builds a space for imagining a different way of relating to nature.

THE VENICE BIENNALE: CZECH AND SLOVAK REPUBLIC PAVILION

The heart of a giraffe in captivity is twelve kilos lighter tells the story of Lenka the giraffe, drawing on the history of Czechoslovakia’s acquisition of animals from the Global South. Interpreted through contemporary ecological and decolonial perspectives, Eva Kotátková’s project of the Czech and Slovak Republic Pavilion at the Venice Biennale builds a space for imagining a different way of relating to nature.

The International Association of Art Critics in Paraguay (AICA-Py) awarded the AICA 2023 Prize to the exhibition Cuadernos de campo (Field Notebooks) by Fidel Fernández, curated by Adriana Almada and exhibited during Pinta Sud 2023 at the Arte Actual gallery in Asuncion.

FIDEL FERNÁNDEZ WINS AICA PARAGUAY 2023 AWARD

The International Association of Art Critics in Paraguay (AICA-Py) awarded the AICA 2023 Prize to the exhibition Cuadernos de campo (Field Notebooks) by Fidel Fernández, curated by Adriana Almada and exhibited during Pinta Sud 2023 at the Arte Actual gallery in Asuncion.

Pinta Sud | ASU presents the third and final edition of Asunción’s Art Week, taking place from August 5-11, 2024. The event will feature art exhibitions, events, and various activities free and open to the public, offering seven days of artistic celebration throughout the city.

ASUNCIÓN IN THE SPOTLIGHT: LAST EDITION OF PINTA SUD

Pinta Sud | ASU presents the third and final edition of Asunción’s Art Week, taking place from August 5-11, 2024. The event will feature art exhibitions, events, and various activities free and open to the public, offering seven days of artistic celebration throughout the city.

Argentine artist La Chola Poblete received a special mention at the Venice Biennale 2024, selected together with artist Samia Halaby.

LA CHOLA POBLETE WAS AWARDED AT THE VENICE BIENNIAL

Argentine artist La Chola Poblete received a special mention at the Venice Biennale 2024, selected together with artist Samia Halaby.

Tania Pardo (Madrid, Spain, 1976) is the new Director of the Museo Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo (CA2M Museum), the museum of contemporary art of the Community of Madrid. Pardo's career until her recent appointment has been built on a detailed work of promotion and visibility of emerging art through the curatorial actions she has developed in numerous Spanish institutions.

INTERVIEW WITH TANIA PARDO, NEW DIRECTOR OF CA2M MUSEUM

Tania Pardo (Madrid, Spain, 1976) is the new Director of the Museo Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo (CA2M Museum), the museum of contemporary art of the Community of Madrid. Pardo's career until her recent appointment has been built on a detailed work of promotion and visibility of emerging art through the curatorial actions she has developed in numerous Spanish institutions.

Art fairs and biennials inhabit the same artistic universe but serve distinct purposes. The former primarily functions as commercial hubs where artworks are bought and sold, whereas biennials act as global stages, celebrating the rich diversity of contemporary art.

BIENNALE UNVEILED: GLOBAL EXHIBITION AND COMMERCE OPPORTUNITIES.

Art fairs and biennials inhabit the same artistic universe but serve distinct purposes. The former primarily functions as commercial hubs where artworks are bought and sold, whereas biennials act as global stages, celebrating the rich diversity of contemporary art.

The Russian Venice Biennale pavilion is hosting a group exhibition of artists from South America organized by Bolivia’s Ministry of Cultures, Decolonization and Depatriarchalizing.

RUSSIA’S VENICE BIENNALE PAVILION WILL HOST BOLIVIA’S PROPOSAL

The Russian Venice Biennale pavilion is hosting a group exhibition of artists from South America organized by Bolivia’s Ministry of Cultures, Decolonization and Depatriarchalizing.

Frieze New York 2024 returns to The Shed in New York with a new curator for Focus, more than 60 galleries from 25 countries and an extensive program of events and activations. This year’s edition will be held from May 1-5.

FRIEZE NEW YORK 2024: CELEBRATING ART AND THE CITY

Frieze New York 2024 returns to The Shed in New York with a new curator for Focus, more than 60 galleries from 25 countries and an extensive program of events and activations. This year’s edition will be held from May 1-5.

The Fundação Biennale de São Paulo announced that Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung will be the chief curator of the 36th São Paulo Biennale, to be held during the second half of 2025.

BONAVENTURE SOH BEJENG NDIKUNG WILL BE THE CHIEF CURATOR OF THE 36TH SÃO PAULO BIENNALE

The Fundação Biennale de São Paulo announced that Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung will be the chief curator of the 36th São Paulo Biennale, to be held during the second half of 2025.

Pinta PArC is the official contemporary art fair in Peru. In its 11th edition –from April 25 to 28– the fair presents an experimental and ambitious program, with unique curatorial projects.

CURATORIAL PROJECTS AT PINTA PArC 2024

Pinta PArC is the official contemporary art fair in Peru. In its 11th edition –from April 25 to 28– the fair presents an experimental and ambitious program, with unique curatorial projects.

La Chola Poblete, Argentine artist and LGBTQ+ rights activist, draws confrontation between historical stereotypes and contemporary visual languages. Her colourful works in diverse media disrupt prevailing power structures and celebrate the rich culture of South American Indigenous peoples. Titled after her hometown, Guaymallén is La Chola’s solo exhibition at PalaisPopulaire, curated by Britta Färber, head of Deutsche Bank’s international art and culture program.

LA CHOLA POBLETE EXHIBITS VIRGINS, COLONIALISM AND EROTICA IN GUAYMALLÉN

La Chola Poblete, Argentine artist and LGBTQ+ rights activist, draws confrontation between historical stereotypes and contemporary visual languages. Her colourful works in diverse media disrupt prevailing power structures and celebrate the rich culture of South American Indigenous peoples. Titled after her hometown, Guaymallén is La Chola’s solo exhibition at PalaisPopulaire, curated by Britta Färber, head of Deutsche Bank’s international art and culture program.

With the opening of Frieze NY last Wednesday, the NY Contemporary sales season has kicked off (if it ever truly stops!). From now until mid-May, it's a whirlwind of fairs and gallery openings, culminating in the grand auctions. May is a crucial time for the US art market calendar and the results will have global repercussion for the remainder of the year.

FRIEZE NEW YORK 2024 – A VIEW FROM THE FLOOR

With the opening of Frieze NY last Wednesday, the NY Contemporary sales season has kicked off (if it ever truly stops!). From now until mid-May, it's a whirlwind of fairs and gallery openings, culminating in the grand auctions. May is a crucial time for the US art market calendar and the results will have global repercussion for the remainder of the year.

El Museo del Barrio presented the exhibition Amalia Mesa-Bains: Archaeology of Memory, the first retrospective exhibition by the pioneering artist, curator, and theorist. Born in 1943 to a Mexican immigrant family, Mesa-Bains has been a leading figure in Chicanx art for nearly half a century.

AMALIA MESA-BAINS: ARCHAEOLOGY OF MEMORY

El Museo del Barrio presented the exhibition Amalia Mesa-Bains: Archaeology of Memory, the first retrospective exhibition by the pioneering artist, curator, and theorist. Born in 1943 to a Mexican immigrant family, Mesa-Bains has been a leading figure in Chicanx art for nearly half a century.

Leonora Carrington’s painting "Les Distractions de Dagobert" (1945), valued between $12 to $18 million, is generating considerable excitement as it heads to auction at Sotheby's this May. Having been in an American collection since 1995, its upcoming sale not only reflects the escalating market demand for Carrington's pieces but also underscores the rising interest in female Surrealist artists.

LEONORA CARRINGTON'S BID FOR LATIN AMERICAN RECORD

Leonora Carrington’s painting "Les Distractions de Dagobert" (1945), valued between $12 to $18 million, is generating considerable excitement as it heads to auction at Sotheby's this May. Having been in an American collection since 1995, its upcoming sale not only reflects the escalating market demand for Carrington's pieces but also underscores the rising interest in female Surrealist artists.

Malta’s pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale presented artist Matthew Attard’s solo project, I Will Follow the Ship. Curated by Elyse Tonna and Sara Dolfi Agostini.

MALTA PAVILION AT THE VENICE BIENNALE 2024

Malta’s pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale presented artist Matthew Attard’s solo project, I Will Follow the Ship. Curated by Elyse Tonna and Sara Dolfi Agostini.

A Comparative Dialogue Act, a project by the Luxembourgish artist Andrea Mancini and the multidisciplinary collective Every Island is representing the Luxembourg Pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale.

ANDREA MANCINI & EVERY ISLAND: LUXEMBOURG PAVILION AT THE VENICE BIENNALE

A Comparative Dialogue Act, a project by the Luxembourgish artist Andrea Mancini and the multidisciplinary collective Every Island is representing the Luxembourg Pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale.

On Thursday, April 18, 2024, the exhibition project Trámites, a duo-show by visual artists Yéssica Montero (1998, Dominican Republic) and Ernesto Rivera (1983, Dominican Republic), opened at the independent spaces of La Sociedad, in Santo Domingo.

TRÁMITES: PROTOCOLS AND STRATEGIES TO EXIST IN EMERGENCIES

On Thursday, April 18, 2024, the exhibition project Trámites, a duo-show by visual artists Yéssica Montero (1998, Dominican Republic) and Ernesto Rivera (1983, Dominican Republic), opened at the independent spaces of La Sociedad, in Santo Domingo.

Commissioned by Facundo de Almeida and curated by Elisa Valerio, the national pavilion of Uruguay presents the work of Eduardo Cardozo with the project Latent.

THE PAVILION OF URUGUAY AT THE 60TH VENICE BIENNALE

Commissioned by Facundo de Almeida and curated by Elisa Valerio, the national pavilion of Uruguay presents the work of Eduardo Cardozo with the project Latent.

The jury of the IV Mediterranean Albert Camus Prize –composed of Javier Gomá, who acts as its president, and N’Goné Fall, Miquel Molina, José Luis Pérez Pont and Anne Prouteau– decided to unanimously award Alfredo Jaar the 2024 edition prize.

ALFREDO JAAR WINS 2024 MEDITERRANEAN ALBERT CAMUS PRIZE

The jury of the IV Mediterranean Albert Camus Prize –composed of Javier Gomá, who acts as its president, and N’Goné Fall, Miquel Molina, José Luis Pérez Pont and Anne Prouteau– decided to unanimously award Alfredo Jaar the 2024 edition prize.

The heart of a giraffe in captivity is twelve kilos lighter tells the story of Lenka the giraffe, drawing on the history of Czechoslovakia’s acquisition of animals from the Global South. Interpreted through contemporary ecological and decolonial perspectives, Eva Kotátková’s project of the Czech and Slovak Republic Pavilion at the Venice Biennale builds a space for imagining a different way of relating to nature.

THE VENICE BIENNALE: CZECH AND SLOVAK REPUBLIC PAVILION

The heart of a giraffe in captivity is twelve kilos lighter tells the story of Lenka the giraffe, drawing on the history of Czechoslovakia’s acquisition of animals from the Global South. Interpreted through contemporary ecological and decolonial perspectives, Eva Kotátková’s project of the Czech and Slovak Republic Pavilion at the Venice Biennale builds a space for imagining a different way of relating to nature.

The International Association of Art Critics in Paraguay (AICA-Py) awarded the AICA 2023 Prize to the exhibition Cuadernos de campo (Field Notebooks) by Fidel Fernández, curated by Adriana Almada and exhibited during Pinta Sud 2023 at the Arte Actual gallery in Asuncion.

FIDEL FERNÁNDEZ WINS AICA PARAGUAY 2023 AWARD

The International Association of Art Critics in Paraguay (AICA-Py) awarded the AICA 2023 Prize to the exhibition Cuadernos de campo (Field Notebooks) by Fidel Fernández, curated by Adriana Almada and exhibited during Pinta Sud 2023 at the Arte Actual gallery in Asuncion.

Pinta Sud | ASU presents the third and final edition of Asunción’s Art Week, taking place from August 5-11, 2024. The event will feature art exhibitions, events, and various activities free and open to the public, offering seven days of artistic celebration throughout the city.

ASUNCIÓN IN THE SPOTLIGHT: LAST EDITION OF PINTA SUD

Pinta Sud | ASU presents the third and final edition of Asunción’s Art Week, taking place from August 5-11, 2024. The event will feature art exhibitions, events, and various activities free and open to the public, offering seven days of artistic celebration throughout the city.

Argentine artist La Chola Poblete received a special mention at the Venice Biennale 2024, selected together with artist Samia Halaby.

LA CHOLA POBLETE WAS AWARDED AT THE VENICE BIENNIAL

Argentine artist La Chola Poblete received a special mention at the Venice Biennale 2024, selected together with artist Samia Halaby.

Tania Pardo (Madrid, Spain, 1976) is the new Director of the Museo Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo (CA2M Museum), the museum of contemporary art of the Community of Madrid. Pardo's career until her recent appointment has been built on a detailed work of promotion and visibility of emerging art through the curatorial actions she has developed in numerous Spanish institutions.

INTERVIEW WITH TANIA PARDO, NEW DIRECTOR OF CA2M MUSEUM

Tania Pardo (Madrid, Spain, 1976) is the new Director of the Museo Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo (CA2M Museum), the museum of contemporary art of the Community of Madrid. Pardo's career until her recent appointment has been built on a detailed work of promotion and visibility of emerging art through the curatorial actions she has developed in numerous Spanish institutions.

Art fairs and biennials inhabit the same artistic universe but serve distinct purposes. The former primarily functions as commercial hubs where artworks are bought and sold, whereas biennials act as global stages, celebrating the rich diversity of contemporary art.

BIENNALE UNVEILED: GLOBAL EXHIBITION AND COMMERCE OPPORTUNITIES.

Art fairs and biennials inhabit the same artistic universe but serve distinct purposes. The former primarily functions as commercial hubs where artworks are bought and sold, whereas biennials act as global stages, celebrating the rich diversity of contemporary art.

The Russian Venice Biennale pavilion is hosting a group exhibition of artists from South America organized by Bolivia’s Ministry of Cultures, Decolonization and Depatriarchalizing.

RUSSIA’S VENICE BIENNALE PAVILION WILL HOST BOLIVIA’S PROPOSAL

The Russian Venice Biennale pavilion is hosting a group exhibition of artists from South America organized by Bolivia’s Ministry of Cultures, Decolonization and Depatriarchalizing.

Frieze New York 2024 returns to The Shed in New York with a new curator for Focus, more than 60 galleries from 25 countries and an extensive program of events and activations. This year’s edition will be held from May 1-5.

FRIEZE NEW YORK 2024: CELEBRATING ART AND THE CITY

Frieze New York 2024 returns to The Shed in New York with a new curator for Focus, more than 60 galleries from 25 countries and an extensive program of events and activations. This year’s edition will be held from May 1-5.

The Fundação Biennale de São Paulo announced that Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung will be the chief curator of the 36th São Paulo Biennale, to be held during the second half of 2025.

BONAVENTURE SOH BEJENG NDIKUNG WILL BE THE CHIEF CURATOR OF THE 36TH SÃO PAULO BIENNALE

The Fundação Biennale de São Paulo announced that Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung will be the chief curator of the 36th São Paulo Biennale, to be held during the second half of 2025.

Pinta PArC is the official contemporary art fair in Peru. In its 11th edition –from April 25 to 28– the fair presents an experimental and ambitious program, with unique curatorial projects.

CURATORIAL PROJECTS AT PINTA PArC 2024

Pinta PArC is the official contemporary art fair in Peru. In its 11th edition –from April 25 to 28– the fair presents an experimental and ambitious program, with unique curatorial projects.

La Chola Poblete, Argentine artist and LGBTQ+ rights activist, draws confrontation between historical stereotypes and contemporary visual languages. Her colourful works in diverse media disrupt prevailing power structures and celebrate the rich culture of South American Indigenous peoples. Titled after her hometown, Guaymallén is La Chola’s solo exhibition at PalaisPopulaire, curated by Britta Färber, head of Deutsche Bank’s international art and culture program.

LA CHOLA POBLETE EXHIBITS VIRGINS, COLONIALISM AND EROTICA IN GUAYMALLÉN

La Chola Poblete, Argentine artist and LGBTQ+ rights activist, draws confrontation between historical stereotypes and contemporary visual languages. Her colourful works in diverse media disrupt prevailing power structures and celebrate the rich culture of South American Indigenous peoples. Titled after her hometown, Guaymallén is La Chola’s solo exhibition at PalaisPopulaire, curated by Britta Färber, head of Deutsche Bank’s international art and culture program.

With the opening of Frieze NY last Wednesday, the NY Contemporary sales season has kicked off (if it ever truly stops!). From now until mid-May, it's a whirlwind of fairs and gallery openings, culminating in the grand auctions. May is a crucial time for the US art market calendar and the results will have global repercussion for the remainder of the year.

FRIEZE NEW YORK 2024 – A VIEW FROM THE FLOOR

With the opening of Frieze NY last Wednesday, the NY Contemporary sales season has kicked off (if it ever truly stops!). From now until mid-May, it's a whirlwind of fairs and gallery openings, culminating in the grand auctions. May is a crucial time for the US art market calendar and the results will have global repercussion for the remainder of the year.

El Museo del Barrio presented the exhibition Amalia Mesa-Bains: Archaeology of Memory, the first retrospective exhibition by the pioneering artist, curator, and theorist. Born in 1943 to a Mexican immigrant family, Mesa-Bains has been a leading figure in Chicanx art for nearly half a century.

AMALIA MESA-BAINS: ARCHAEOLOGY OF MEMORY

El Museo del Barrio presented the exhibition Amalia Mesa-Bains: Archaeology of Memory, the first retrospective exhibition by the pioneering artist, curator, and theorist. Born in 1943 to a Mexican immigrant family, Mesa-Bains has been a leading figure in Chicanx art for nearly half a century.

Leonora Carrington’s painting "Les Distractions de Dagobert" (1945), valued between $12 to $18 million, is generating considerable excitement as it heads to auction at Sotheby's this May. Having been in an American collection since 1995, its upcoming sale not only reflects the escalating market demand for Carrington's pieces but also underscores the rising interest in female Surrealist artists.

LEONORA CARRINGTON'S BID FOR LATIN AMERICAN RECORD

Leonora Carrington’s painting "Les Distractions de Dagobert" (1945), valued between $12 to $18 million, is generating considerable excitement as it heads to auction at Sotheby's this May. Having been in an American collection since 1995, its upcoming sale not only reflects the escalating market demand for Carrington's pieces but also underscores the rising interest in female Surrealist artists.

Malta’s pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale presented artist Matthew Attard’s solo project, I Will Follow the Ship. Curated by Elyse Tonna and Sara Dolfi Agostini.

MALTA PAVILION AT THE VENICE BIENNALE 2024

Malta’s pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale presented artist Matthew Attard’s solo project, I Will Follow the Ship. Curated by Elyse Tonna and Sara Dolfi Agostini.

A Comparative Dialogue Act, a project by the Luxembourgish artist Andrea Mancini and the multidisciplinary collective Every Island is representing the Luxembourg Pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale.

ANDREA MANCINI & EVERY ISLAND: LUXEMBOURG PAVILION AT THE VENICE BIENNALE

A Comparative Dialogue Act, a project by the Luxembourgish artist Andrea Mancini and the multidisciplinary collective Every Island is representing the Luxembourg Pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale.

On Thursday, April 18, 2024, the exhibition project Trámites, a duo-show by visual artists Yéssica Montero (1998, Dominican Republic) and Ernesto Rivera (1983, Dominican Republic), opened at the independent spaces of La Sociedad, in Santo Domingo.

TRÁMITES: PROTOCOLS AND STRATEGIES TO EXIST IN EMERGENCIES

On Thursday, April 18, 2024, the exhibition project Trámites, a duo-show by visual artists Yéssica Montero (1998, Dominican Republic) and Ernesto Rivera (1983, Dominican Republic), opened at the independent spaces of La Sociedad, in Santo Domingo.

Commissioned by Facundo de Almeida and curated by Elisa Valerio, the national pavilion of Uruguay presents the work of Eduardo Cardozo with the project Latent.

THE PAVILION OF URUGUAY AT THE 60TH VENICE BIENNALE

Commissioned by Facundo de Almeida and curated by Elisa Valerio, the national pavilion of Uruguay presents the work of Eduardo Cardozo with the project Latent.

The jury of the IV Mediterranean Albert Camus Prize –composed of Javier Gomá, who acts as its president, and N’Goné Fall, Miquel Molina, José Luis Pérez Pont and Anne Prouteau– decided to unanimously award Alfredo Jaar the 2024 edition prize.

ALFREDO JAAR WINS 2024 MEDITERRANEAN ALBERT CAMUS PRIZE

The jury of the IV Mediterranean Albert Camus Prize –composed of Javier Gomá, who acts as its president, and N’Goné Fall, Miquel Molina, José Luis Pérez Pont and Anne Prouteau– decided to unanimously award Alfredo Jaar the 2024 edition prize.

The heart of a giraffe in captivity is twelve kilos lighter tells the story of Lenka the giraffe, drawing on the history of Czechoslovakia’s acquisition of animals from the Global South. Interpreted through contemporary ecological and decolonial perspectives, Eva Kotátková’s project of the Czech and Slovak Republic Pavilion at the Venice Biennale builds a space for imagining a different way of relating to nature.

THE VENICE BIENNALE: CZECH AND SLOVAK REPUBLIC PAVILION

The heart of a giraffe in captivity is twelve kilos lighter tells the story of Lenka the giraffe, drawing on the history of Czechoslovakia’s acquisition of animals from the Global South. Interpreted through contemporary ecological and decolonial perspectives, Eva Kotátková’s project of the Czech and Slovak Republic Pavilion at the Venice Biennale builds a space for imagining a different way of relating to nature.

The International Association of Art Critics in Paraguay (AICA-Py) awarded the AICA 2023 Prize to the exhibition Cuadernos de campo (Field Notebooks) by Fidel Fernández, curated by Adriana Almada and exhibited during Pinta Sud 2023 at the Arte Actual gallery in Asuncion.

FIDEL FERNÁNDEZ WINS AICA PARAGUAY 2023 AWARD

The International Association of Art Critics in Paraguay (AICA-Py) awarded the AICA 2023 Prize to the exhibition Cuadernos de campo (Field Notebooks) by Fidel Fernández, curated by Adriana Almada and exhibited during Pinta Sud 2023 at the Arte Actual gallery in Asuncion.

Pinta Sud | ASU presents the third and final edition of Asunción’s Art Week, taking place from August 5-11, 2024. The event will feature art exhibitions, events, and various activities free and open to the public, offering seven days of artistic celebration throughout the city.

ASUNCIÓN IN THE SPOTLIGHT: LAST EDITION OF PINTA SUD

Pinta Sud | ASU presents the third and final edition of Asunción’s Art Week, taking place from August 5-11, 2024. The event will feature art exhibitions, events, and various activities free and open to the public, offering seven days of artistic celebration throughout the city.